Resilience, before and after the election

With only a few days left before the Presidential election, the city of Washington, D.C., is humming with anxiety.

The taxi driver from Ethiopia asks, “Have you voted already?”

Two people jog toward me in a park north of the Capitol, deep in conversation. As they pass, I hear one of them say, with alarm, “….and the difference is only 3%!”

My friend, an environmental lawyer with the Interior Department, meets us at the restaurant, pulls off her jacket, takes her seat, and bursts out, “Make me feel better about the election!”

Now would be a good moment to talk about stress. As Kelly McConagil points out in “How You Can Find the Good in a Nasty Election Cycle,” many Americans are experiencing not just everyday stress, but moral distress, “that potent combination of moral outrage, worrying about harm that may be done, and feeling powerless to do anything about it.”

The election cycle is one source of our collective sense of stress. Another is climate change. Of course, the two stressors are linked, since the outcome of Tuesday’s election will determine whether or not our next President pulls out of the Paris Agreement and effectively puts an end to global efforts to prevent runaway climate change.

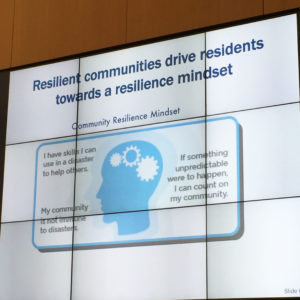

The topic of stress and resilience is what brought me to D.C. as one of the panelists at a two-day conference on “Building Human Resilience for Climate Change.” Held on November 3-4 at the headquarters of the National Psychological Association in Washington, D.C., the conference was organized by International Transformational Resilience Coalition (ITRC). ITRC was launched in 2014, and is now a network composed of hundreds of mental health, faith, youth, and educational leaders that are focused on the need to prepare human beings to cope constructively with the psychological, spiritual, and psycho-social impacts of climate change. Even more ambitiously, ITRC seeks to help people “use climate adversities as transformational catalysts to learn, grow, and increase well-being.” ITRC recognizes that trauma lies ahead of us, as global average temperatures rise toward 2˚ Centigrade (3.4˚ Fahrenheit). Much suffering can be prevented if we address the risks proactively.

As you might expect – given the topic – the conference was intense, and addressed a range of challenging questions. How does climate disruption affect our mental health? What are the psychological impacts of flooding, droughts, extreme weather events, and rising temperatures? Where do we see “secondary trauma” associated with climate change, such as “moral distress,” “compassion fatigue,” helplessness, hopelessness, and burnout? How does climate disruption affect a community’s social health, contributing to a rise in aggression, crime, and violence? What is the difference between “disaster-preparedness” and “resilience”? What practices and policies help communities to foster robust social support networks? What skills help us to develop our personal resilience, our capacity as individuals to bounce back – and even grow – in the face of acute or chronic trauma?

In one of the afternoon workshops, I was a panelist alongside two other faith leaders – Hugh G. Bryne (who teaches meditation and works with people to cultivate mindfulness in daily life with the Insight Meditation Community of Washington (IMCW), and is cofounder of the Mindfulness Training Institute of Washington) and Imam Saffet Abid Catovic (who is a fellow at GreenFaith, Co-chair and founder of the Green Muslims of New Jersey, and a founding board member of the Global Muslim Climate Network). Moderated by Mark C. Johnson (who is Executive Director, The Center and Library for the Bible and Social Justice), the panel gave each of us a chance to reflect on the ways that the doctrines and practices of our faith contribute to building human resilience to climate change.

In my remarks I gave a brief summary of my three-part “framework of the heart” for spiritual resilience, and I mentioned my article on the roles that faith communities can play in addressing the climate crisis.

I was touched by the eager participation of members of the audience in the Q & A that followed. As one person exclaimed, climate change is the biggest pastoral and existential issue we’ve ever faced. She’s right. Her comment made me think of children who fear they have no future; of young adults who decide not to have children because they don’t want to bring new beings into such a world; of the elders who have confided to me that they’re glad to be old – they won’t have to endure what’s coming.

If post-traumatic stress disorder is real, so is “pre-traumatic stress disorder.” We’re living in it. That is what forensic psychiatrist (and one of the speakers at the conference) Lise Van Susteren said in an interview with Esquire last July, “When the End of Human Civilization Is Your Day Job.” Knowing that we can expect climate disasters in the years ahead makes us frightened, sad, and angry; we feel unsettled and obsessed.

I’m not going to spin you a cheery story that in fact all is well in the world outside us or in the world within us. It’s not. That’s why it is so important to develop initiatives that build resilience on a personal and societal level. I look forward to seeing how faith communities can lead the way.

In the meantime, I wish my readers a deep sense of ease, the kind of ease that comes from facing reality as it is, while keeping an open heart. In a stressful time, we can always take a good, deep breath and become present to the here and now (Ah! This breath!).

We can carry out actions that reflect our values. (If you read this before November 8 and haven’t yet done so, please vote on Tuesday.)

And we can renew our sense of purpose. My spirits lift whenever I read the note that my mother wrote out by hand and pinned to her bulletin board: Whenever you despair for the world, stop and ask yourself: What kind of world am I creating?

Asking – and answering – that question is an essential ingredient in every good recipe for resilience.

For more information about ITRC, contact: tr@trig-cl.org

2 Responses to “Resilience, before and after the election”

Karen Ribeiro

Heartbreak shatters the shell around the heart and awakens its capacity to love.

Dear Margaret, your important work and reflections here inspire me to share an insight I had this past weekend during a very challenging conversation about how and why one makes the effort to expand his or her consciousness. If humans are created in Gods image so that the magnificence of creation can be experienced and, perhaps, reflected back to the divine, what we think, feel, say, and do in every moment is either a conscious choice (a gift of gratitude) or some degree of unconsciousness (with potentially harmful consequences).

Let’s all choose to be as awake as we possibly can each moment of this precious life!

mbj

Karen, thank you for this invitation to keep our minds steady, our hearts open, and our purpose clear! Yes, it does take work, effort, practice, and intention to create the conditions for our consciousness to expand…. but the reward is that gradually we become who we were made to be — people living in communion with — even union with — the divine. May it be!