What are the connections between the novel coronavirus and the climate crisis? Margaret is the first speaker on a panel sponsored by UCC Council for Climate Justice, convened on April 1, 2020, by the Rev. Brooks Berndt, PhD (Minister for Environmental Justice, UCC). Other panelists include the Rev. Dr. Leah Schade (Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship, Lexington Theological Seminary), the Rev. Dr. Jim Antal (Special Advisor on Climate Justice to UCC General Minister and President), and Penny Hooper (Leadership Council Chair, North Carolina Interfaith Power & Light)

Author Archives: mbj

Earth Day 2020 comes at a tumultuous time. COVID-19 has upended our lives. The number of infections keeps soaring world-wide and entire countries are sheltering in place.

Out of caution, many are keeping physical distance from each other. But out of compassion, many are helping any way they can — staying connected by phone or internet with those who are lonely; sewing masks for desperate health care workers; making donations to groups that help migrants and the homeless; pushing for policies that protect the lowest-earning members of society.

If there was ever a time in which humanity should finally recognize that we belong to one connected family on Earth, this should be it. We share a single planet, drink from the same water and breathe the same air.

So, whether hunkered down at home or hospital, or working on the front lines, we are all doing our part to face a common enemy together. When COVID-19 is finally behind us, instead of returning to normal life, we must hold on to these lessons in the fight against climate change.

Below are 6 lessons the coronavirus pandemic can teach us about our response to climate change.

- Science matters

We can save lives by funding, accessing and understanding the best science available. The science on climate change has been clear for decades, but we’ve failed in communicating the danger to the public, leading to slow action and widespread denial of the facts.

- How we treat the natural world affects our well-being.

The loss of habitat and biodiversity creates conditions for lethal new viruses and diseases like COVID-19 to spill into human communities. And if we continue to destroy our lands, we also deplete our resources and damage our agricultural systems.

- The sooner we mobilize for action, the less suffering will take place.

Quick and drastic action can flatten the curve for coronavirus and free up healthcare resources, lowering death rates. Similarly, drastic action on climate change could reduce food and water shortages, natural disasters and sea level rise, protecting countless individuals and communities.

- We have the ability to make drastic changes very quickly.

When sufficiently motivated, we can suspend business as usual to help each other. All over the world, healthy people are changing their lifestyles to protect the more vulnerable people in their communities. Similar dedication for climate change could transform our energy consumption immediately. All of us can make a difference and play an important role in the solution.

- All of us are vulnerable to crisis, though unequally.

Those with underlying social, economic or physical vulnerabilities will suffer most. A society burdened with social and economic inequality is more likely to fall apart in a crisis. We must also recognize that industries and people who profit from an unjust status quo will try to interrupt the social transformation that a crisis requires.

- Holding on to a vision of a just, peaceful and sustainable Earth will give us strength for the future.

Earth Day 2020 will be remembered as a time when humanity was reeling from a pandemic. But we pray that this year will also be remembered as a time when we all were suddenly forced to stop what we were doing, pay attention to one another and take action.

Business as usual — digging up fossil fuels, cutting down forests and sacrificing the planet’s health for profit, convenience and consumption — is driving catastrophic climate change. It’s time to abandon this destructive system and find sustainable ways to inhabit our planet.

What would it look like if we emerged from this pandemic with a fierce new commitment to take care of each other? What would it look like to absorb the lessons of pandemic and to fight for a world in which everyone can thrive?

On this 50th anniversary of Earth Day, as fear and illness sweep the globe, we listen for voices that speak of wisdom, generosity, courage and hope. And as always, we find solace in the natural world. In the suddenly quiet streets and skies, we can hear birds sing.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

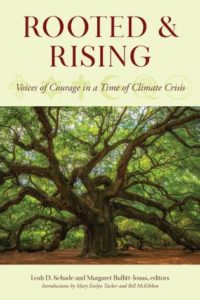

This essay was co-written by Margaret Bullitt-Jonas and Leah D. Schade, co-editors of the book Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), an anthology of essays from religious environmental activists on finding the spiritual wisdom for facing the difficult days ahead. This essay was published by Earth Day Network on March 25, 2020.

Arizona PBS broadcast an interview with the Rev. Dr. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas as part of a report about blasting at the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument to build President Trump’s border wall (March 2, 2020).

The Rev. Dr. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas preached on February 23, 2020, at Grace St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Tucson, AZ, on “Transfiguration and radiant Earth.”

In this sermon, Margaret speaks about the world as a sacred, living whole, lit up with the glory of God — a perception of reality shared by Moses, Jesus, and countless other people of faith and good will. When we know that God’s Creation is sacred, cherished and precious in God’s sight, we rise up to protect it from further harm. The mystic becomes a prophet and activist.

Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis, co-edited by Margaret and Leah D. Schade, was released in November 2019 by Rowman & Littlefield. It features 21 essays by a wide range of individuals–scientists, scholars, faith leaders, and activists–who write about their sources of strength, wisdom, and hope as they grapple with the climate crisis. The book includes study questions and spiritual practices, making it an excellent choice not only for individual reflection, but also for study groups, classes, and interfaith conversations. (Use this code for a 30% off discount from the publisher: RLFANDF30.)

Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis, co-edited by Margaret and Leah D. Schade, was released in November 2019 by Rowman & Littlefield. It features 21 essays by a wide range of individuals–scientists, scholars, faith leaders, and activists–who write about their sources of strength, wisdom, and hope as they grapple with the climate crisis. The book includes study questions and spiritual practices, making it an excellent choice not only for individual reflection, but also for study groups, classes, and interfaith conversations. (Use this code for a 30% off discount from the publisher: RLFANDF30.)

“In the face of an absolute emergency, the voices in Rooted and Rising represent an important source of inspiration and challenge. There is no time left for delay or half-heartedness in our response to the climate crisis, and these authors call on all of us to do everything we can for the sake of our precious planet.” — Fletcher Harper, executive director, GreenFaith

“This book put new steel in my spine and fired up my resolve. You need this book, and the Earth needs you to take its message and resources to heart.”

— Brian D. McLaren, author/speaker/activist

The following sermon for the Second Sunday after Christmas Day is adapted from a sermon I delivered in 2011. It is posted at SustainablePreaching.org (January 5, 2020).

Sermon for the Second Sunday after Christmas Day

Jeremiah 31:7-14

Psalm 84: 1-8

Ephesians 1:3-6, 15-19

Matthew 2: 1-12

Journeying with the wise men

Happy are the people whose strength is in you! whose hearts are set on the pilgrims’ way. – Psalm 84:4

When I think of the three kings, what leaps first to mind are the crèches I unpack every year a couple of weeks before Christmas. On the piano in the living room I put the tall, earthenware figures of Mary, Joseph, and the baby, of the shepherds and sheep, and — yes — of the three kings and their camels. On the mantelpiece goes a miniature nativity set in which each teeny-tiny figure is made of clay, delicately painted, and no more than one inch high. On the coffee table I put the plastic figures and the cheap wooden stable that children can play with to their heart’s content without making their grandmother worry that something will break. No crèche is complete without its three kings, and when the Twelve Days of Christmas are over, back go the kings and camels into their boxes, where they spend the rest of the year stored in the basement.

Reflecting on today’s Gospel, I got to thinking: what would happen if the wise men walked out of those crèches and into our lives? What would happen if these figures — so easy to trivialize as nothing more than decorative props for a mid-winter festival that we pack away when the festival is done — what if the wise men actually came to life for us? What if their journey informed and deepened our own spiritual search, and propelled it forward? So I began to read the story for its spiritual significance, wondering if it might be read as a sacred, archetypal story about how we grow in intimacy with God.

Four parts of the story stand out to me.

First, of course, is the star, that mysterious, shining presence that startles the wise men and launches their search. Ancient tradition held that an unusual star could appear in the skies to mark the birth of someone special, such as a king. That is how the wise men interpret what they see: something out of the ordinary is taking place, something truly significant is afoot, and out the door they go, leaving their ordinary lives behind as they follow the light wherever it leads.

Let’s pause to note that even though every painting, movie, and Christmas card that depicts the journey of the wise men shows a dazzling star above their heads, we don’t actually know from the biblical story whether anyone but the wise men can see that star. King Herod, the chief priests and scribes don’t seem to know anything about the star until the wise men arrive in Jerusalem and tell them about its rising. So the star may be visible to the eye or it may be perceptible only to one’s inward sight; it may be seen or it may be unseen. Either way, it signals the birth of something new in the world. It heralds a presence and power just now being born. The wise men are wise because they spot the star and set everything aside to follow where it leads.

Maybe every spiritual journey begins with a star. At some point we get a sense — perhaps a very vague one — that there is something more to life than the ordinary round of tasks and responsibilities, something above, beyond, or maybe within material reality that can give a larger meaning and purpose to our days, something that is beautiful and shining and that lights up the world. So we set out on a quest to follow that star and to see where it leads. We may name the quest in different ways — maybe we call it a search for meaning or wholeness, a search for happiness or peace. Maybe we seek to know that we are loved, or to draw closer to the divine Source of love. Maybe, as some Greeks say to Philip in the Gospel of John, we express our desire in a simple, straightforward way: “We wish to see Jesus” (John 12:21). However we name that desire, deep down we want to know God. And so, like the wise men, we set out, and what beckons us forward is a star, a subtle, shining presence that keeps company with us, and that we follow as best we can.

For most of us, most of the time, following the leadings of God is not like having a GPS in the car, delivering clear-cut instructions: “Turn left in .2 miles; take the freeway; turn right in 4.3 miles.” Like it or not, the star of Bethlehem is more elusive than that, so we have to develop a stance of careful listening and open inquiry, and a practice of prayer that makes us more sensitive to the glimmers of the holy. It takes practice to stay attentive to the star, for, as Boris Pasternak once wrote, “When a great moment knocks on the door of your life, it is often no louder than the beating of your heart, and it is very easy to miss it.”

The star is the first thing that catches my attention in this story. The second is Jerusalem. Where does the star lead the wise men? Straight to Jerusalem, straight into the center of political and economic power, where King Herod the Great, a client king appointed by Rome, rules with the same ferocity that Stalin wielded over his own country in the 1930’s. We might wish that following a spiritual path were only an individual and interior enterprise — that following the star meant nothing more than developing a personal practice of prayer or going away on periodic retreats. There are plenty of contemporary books and speakers out there that define spirituality in a very individualistic way as being mindful of your own mind and cultivating your own soul — and of course that is definitely part of the journey. But right from the beginning, from the very moment that Christ is born, it’s clear that following his star also means coming to grips with the social and political realities of one’s time. Being “spiritual,” for Christians, is not just an interior, individual project of “saving your soul” — it also has a civic dimension, a political dimension, and as the wise men faithfully follow the star, they are drawn straight into the darkness and turmoil of the world, where systemic power can be used to dominate and terrify. Without intending it or knowing it, the wise men even contribute to Herod’s program of terror, for Herod takes the information that they give him and uses it to order the slaughter of all the children under the age of two who live in Bethlehem.

Following the star evidently means being willing to become conscious of the darkness of the world, and even to perceive how we ourselves are implicated in that darkness. The taxes I pay help subsidize fossil fuels; the clothes I wear and the electronic devices I use may have a vast but hidden social and environmental cost. If I drive a gas-powered car, with every turn of the ignition key, I add to global warming. Until I recognize how I am caught up in and contribute to the contradictions and injustices of our political and economic system, I am not following the star and accompanying the wise men into Jerusalem.

And let’s notice, too, that King Herod trembles at news of the star — in fact, its rising frightens him. The powers that be are terrified when God in Christ draws near, for God’s love is always a threat to those powers; it opposes everything in us and around us that is selfish, greedy, and motivated by the wish to dominate, control, and possess. As I read it, the wise men needed to get to know those powers, both within themselves and in the world around them, if they were going to find and follow Christ.

So they entered Jerusalem and faced the darkness. Then, keeping their eyes on the star, they kept going, “until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw that the star had stopped, they were overwhelmed with joy” (Matthew 2:9b-10).

This is the third part of the story: the encounter with Christ. What a beautiful line that is — “when they saw that the star had stopped, they were overwhelmed with joy.” The long, long journey with all its uncertainties and privations, its cold nights and its restless, ardent searching, has reached its fulfillment. The star has stopped, and the wise men can be at peace at last, they have arrived at last, they have found what they were looking for, at last! They enter the house, they see Mary and the child, and they fall to their knees in a gesture of deep reverence and humility.

Do we know what that’s like? Of course we do. We glimpse such moments whenever time seems to stop, when, for instance, our minds grow very quiet in prayer, we surrender our thoughts, and we seem to be filling with light. Or maybe it happens when we gaze at something that captures our complete attention — maybe a stretch of mountains or the sea, or when we take a long, loving look into a child’s sleeping face, or when we are completely absorbed in a piece of music. In moments like these, it can feel as if we are gazing through the object on which we gaze, and seeing into the heart of life itself. Love is pouring through us and into us, and all we can do is throw up our hands, fall inwardly to our knees, and offer as a gift everything that is in us, just as the wise men open their treasure chests and offer everything that is in them. Worship is what happens when we come into the presence of what is really real. When we come to the altar rail at the Eucharist, whether we choose to stand or whether we kneel as the wise men did, like them we stretch out our hands to offer everything that is in us, and like them we receive — we take in — the living presence of Christ.

Finally, the fourth part of the story is its closing line: “… having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they left for their own country by another road” (Matthew 2:12). In other words, the wise men refused to cooperate with Herod. They deceived him. They resisted him. The wise men have been called the first conscientious objectors in the name of Christ. They are the first in a long line of witnesses to Christ who from generation to generation have carried out acts of non-violent civil disobedience in Jesus’ name. The journey of the wise men is our journey, too, for, as Gregory the Great reportedly remarked in a homily back in the 7th century: “Having come to know Jesus, we are forbidden to return by the way we came.”

So, as we set out together into a new year, I hope that you will join me in keeping the wise men at our side, rather than packing them away somewhere in a box.

Like them, we can attune ourselves to the guiding of the star and renew our commitment to prayer and inward listening.

Like them, we can enter Jerusalem and all the dark places of our world and soul, following where God leads, and trusting that God’s light will shine in the darkness.

Like them, we can make our way to Christ, and kneel in gratitude.

And like them, we, too, can rise to our feet with a new-fired passion to be agents of justice and healing, and a renewed desire to give ourselves to God, for “happy are the people whose strength is in [God, and] whose hearts are set on the pilgrims’ way.”

This article by reporter Steve Pfarrer of Daily Hampshire Gazette includes an interview with Margaret Bullitt-Jonas about her new book, ROOTED & RISING, co-edited with Leah Schade. The original article includes many photos (Dec. 24, 2019).

As the digital revolution has sped up the pace of life, with cell phones, Twitter, Facebook and 24/7 news coverage seeming to leave no “off” switch, so does the news of climate change seem to come at an ever-increasing clip.

Glaciers in Greenland melting faster than had been predicted? Check. Worldwide carbon dioxide levels reaching record new levels? Check. Animal species going extinct faster than had been expected? Check. July 2019 determined to be the hottest month ever since record-keeping began more than a century ago? Check.

If you’re experiencing anxiety — or something worse, like hopelessness or despair — about the future of the planet, you’re not alone. The American Psychological Association published a guide for therapists two years ago to help them counsel patients about what some have also called “eco-anxiety.” The report stated in part that negative psychological responses to climate change, such as conflict avoidance, hopelessness, fatalism and fear — even aggression and violence — were growing.

“These responses are keeping us, and our nation, from properly addressing the core causes of and solutions for our changing climate, and from building and supporting psychological resiliency,” the report added.

Beth Fairservis, a pastoral counselor and climate activist in Williamsburg, has talked to some of her clients about climate change over the past several years. But this summer, she says, “There seemed to be a real shift … it seemed like every client was talking about it, that people were starting to feel a sense of ‘Oh my God, this is different from anything in recorded history.’ ”

Fairservis, who also develops theatrical productions that address climate change, believes the high visibility this year of young Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, who attracted worldwide media attention with her calls for immediate action on the issue, may have raised awareness on climate issues in a way that myriad scientific and media reports have been unable to do.

“I think for a lot of people, there’s a certain sense of mortality,” said Fairservis. “We’re in shock. We’re looking at profound changes to our way of life. Climate change could upend so many things we take for granted, like food supplies, electricity, the typical changing of the seasons.” Client change is not necessarily the only thing troubling her clients, Fairservis notes, but for many “it’s at the core of their issues.”

Seeking community

But she and others in the Valley who are grappling with the disturbing changes to our environment — and the prospect of more severe problems in the future, from crippling heat to rising seas to depletion of food supplies — say there are ways to address this. There’s no one solution, they say, nor can we expect some last-minute technical solution to save the planet. But Fairservis, for one, says there’s much to be gained by continuing to push government leaders on addressing the issue, finding value in day-to-day life, and forging stronger connections to one’s community.

“One simple thing you can do is write down what you’re grateful for,” said Fairservis, whose background includes the study of Buddhist traditions and mindfulness. “And we can reconnect with our bodies and our emotions. We’ve become distanced from them by our society and technology.”

Geoffrey Hudson found some perspective on climate change by doing something he loves best: composing music. The Pelham cellist and classical composer remembers reading a newspaper article a few years ago on climate change in which a scientist expressed frustration that what he and other climatologists were documenting didn’t seem to be resonating with people — at least not emotionally.

“That really struck a chord in me,” said Hudson. “I had never seen a connection between the issue and my music, but now I did. Music can really build emotional connections, on a lot of different levels.”

Hudson wrote an hour-long oratorio, “Passion for the Planet,” scoring the piece for adult and younger singers and a 12-member chamber ensemble. The music looks both at the ominous side of climate change, with a reference to the famous “hockey stick” graph from the 1990s that revealed a dramatic rise in global temperatures in the 20th century, but it also offers a message of hope in its later movements: a sense that, as Hudson puts it, “We’re all in this together. You don’t have to be alone.”

When the piece had its debut at Sage Hall at Smith College this past summer, it sold out, he said, and the line of would-be concert-goers extended out the door and down the block. It was performed by the Illuminati Vocal Arts Ensemble — including Hudson’s wife, singer Alisa Pearson — and the Hampshire Young People’s Chorus. Afterward, Hudson said, people seemed deeply moved and happy they’d been part of the event.

“Music is not going to solve climate change, but it can bring us together and give us a greater sense of community and how we have to work together to confront this,” he said. He noted that he and Pearson have an 11-year-old daughter and are very concerned about what the future may offer her. But he suggested climate change be viewed as a large boat that people are slowly trying to turn around and steer in the opposite direction.

“You work as hard as you can to turn it around, and you may think it’s not turning, but eventually it does,” he said.

Lives of the spirit

Margaret Bullitt-Jonas has been concerned about climate change for over three decades, ever since the problem was first tagged as “global warming” in the 1980s. A former Episcopal minister for Grace Church in Amherst, Bullitt-Jonas has devoted herself to climate activism for 20 years and for the last six years has worked full time for the Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts on climate issues — writing, leading retreats, speaking on the issue and taking part in interfaith services.

Bullitt-Jonas, of Northampton, sees climate change as a vital issue for people in the faith community to address, just as U.S. churches previously responded to social justice issues such as the civil rights movement. On an individual level, she adds, it’s also important for people to take stock of what’s important in their life. Like Fairservis, she counsels people to stop and consider what they feel grateful for as a way to keep climate grief at bay.

“It’s clear that our way of life is not working for a lot of people or the Earth,” she says. “And it can feel that whatever we’re doing to try and lower our footprint on the planet is just so insignificant … but in a way, we have an opportunity now to reassess how we want to live our lives.”

Bullitt-Jonas has also co-edited, with a Lutheran pastor and academic in Kentucky, Lean Schade, a recent collection of essays, “Rooted & Rising,” on the topic. The contributors — faith leaders, climate activists, scientists and others — write about their own responses to climate change and the need to be resilient.

And Bullitt-Jonas and Schade write in an introduction to the book that the crisis could become “a catalyst for spiritual and societal transformation. It is our deepest, most fervent hope that the wisdom of the world’s religious and faith traditions can help to midwife whatever new life will be born out of this cataclysmic time.”

Another climate activist, Sarah Metcalf of Northampton, says she went through a period of serious depression a few years ago after giving a sermon on climate despair at the Unitarian Society in Northampton, where she serves on a committee examining climate change. “The situation seems so dire and disheartening … it felt like whatever I was doing [to fight climate change] was nothing more than a symbolic gesture.”

But Metcalf, while not claiming any sudden burst of optimism on the issue, says there are some basic steps you can take to counter that sense of hopelessness. “Go outside a lot — love being in the natural world in all its beauty and variety. Meet other people, stay active. Help others. Become more self-sustaining. Being alone and obsessing on this subject is not the way to go.”

And Metcalf, a writer and singer — she sang in “Passion for the Planet” with the Illuminati Vocal Arts Ensemble — has also reconsidered the value of the personal steps she’s taken to try and reduce her carbon footprint. Though stressing she’s fortunate enough to be able to swing some things financially that others cannot, she said that, as one example, replacing her old Subaru with an electric car “has made my heart feel a little lighter — you know, ‘Here’s something personal I can do.’ ”

And Metcalf holds out this hope: that when facing an emergency, humanity can rally and show collective courage and action. “We rush into burning buildings to save strangers,” she said. “And right now, our planet is burning.”

This op-ed, co-written by Leah Schade and Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, was published in newspapers in Louisville, KY; Frankfort, KY; and Northampton, MA (December 18, 2019).

The picture of Greta Thunberg on the cover of Time magazine as its 2019 Person of the Year is both inspiring and sobering.

Standing on an outcropping of rocks at the ocean’s edge, she gazes toward the sea. The splashing waves at her feet are a poignant reminder that signs of the climate crisis are all around us.

The world’s oceans are rapidly losing oxygen — it’s as if they are beginning to suffocate. Many of the oceans’ vital ecosystems are at risk of collapse. And new research indicates that rising seas due to global warming could affect three times more people by 2050 than previously thought. Some of the world’s great coastal cities will likely be erased, sending the number of climate refugees into the millions.

Given this dire projection, along with news about wildfires, hurricanes, droughts, floods and mass species extinction, the effects of climate change have reached biblical proportions. This is why Greta Thunberg is a prophet for our time.

In August 2018, at age 15, this teenager stood with her sign, “School strike for the climate,” on the steps of the Swedish Parliament. Since then, her lone voice has struck a chord that has reverberated around the world. She has inspired young people across the planet to organize climate strikes calling on adults to take action on global warming.

Millions of students have mobilized in protests worldwide. Her stirring speech at the United Nations was a prophet’s call to repentance for the ecological sins we have committed against this planet and those who will inherit the mess we have made.

Of course, she is also vilified by many, including the presidents of Brazil and the United States. They mock her, attack her and ridicule her. That’s what happens when prophets speak truth to power. But people are listening to her message. World leaders are paying attention. She is cutting through the hubbub of noise, distraction, and lies, and telling the truth without apology.

This is exactly the time for faith communities to step up alongside Greta and the climate generation to offer support and leadership during this climate crisis.

More and more people are asking: “What can we do?” Through collaboration and community-building, houses of worship can help their neighbors find innovative answers to that question.

Pastors, priests, imams, rabbis and spiritual leaders of the world’s religions are perfectly situated to address these issues from a theological and scriptural perspective in order to galvanize the faithful to respond. Just as churches and synagogues were the moral engine that powered the civil rights movement, so now are houses of worship needed to harness the energy of the faithful to act.

In many ways this is already happening. Organizations such as Greenfaith, Interfaith Power & Light, ecoAmerica’s Blessed Tomorrow, and the Poor People’s Campaign are reaching across religious and political divides to educate and activate people of faith.

Churches are installing solar panels. Mosques are planting community gardens. Synagogues are hosting sessions on community organizing around climate change. People of faith are protesting pipelines, willing to be arrested for their nonviolent civil disobedience.

This is a moment when the faith community must not stand on the sidelines. If you are a member of a congregation, encourage your faith leader to preach and teach about what your scriptures say about this good Earth. If you are a faith leader, talk with your colleagues about how you can spark the sacred fire that has the power to ignite a revolution of justice.

This is an issue that affects every person on our planet, especially “the least of these” who bear the brunt of the effects of climate change. The climate crisis is a global, national, state and local issue, and faith leaders must not only become well-informed and well-read on this topic, they must also be bold prophets for justice.

The climate emergency offers the opportunity for new life to be breathed into community movements as people of faith join efforts to combat climate change.

As Greta has shown us — it’s time for us all to be prophets.

Margaret was interviewed for an article by reporter Steve Pfarrer, “Confronting climate change: Facing down the emotional and psychological costs of environmental chaos” (Daily Hampshire Gazette, Dec. 24, 2019).

With Leah Schade, Margaret co-wrote an op-ed, “Greta Thunberg compels us all to be prophets,” published by newspapers in Louisville, KY; Frankfort, KY; and Northampton, MA (Dec. 18, 2019).