A presentation by the Rev. Dr. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas for Creation Justice Ministries on March 24, 2022. Facilitated by Avery Davis Lamb, Co-Executive Director of Creation Justice Ministries, this online workshop was part of CJM’s ongoing exploration of how the church might become a hub of resilience in the midst of the spiritual and physical storms of the climate crisis. A recording of this conversation, along with CJM’s other workshops on climate resilience, is available on their YouTube channel. A PDF is available for download.

Let’s begin by taking a quick pulse.

-

- How many of you have heard a sermon about the climate emergency and our moral obligation as Christians to tackle it? Please raise your hand.

- How many of you preachers – lay or ordained – have preached a sermon about the climate emergency and our moral obligation as Christians to tackle it?

- How many of you preachers intend to preach a climate sermon sometime soon, and how many of you non-preachers will give them your full support when they do?

I hope everybody’s hands went up that time!

For a while now I’ve been traveling around, preaching about climate change, and you’d be amazed how many times I’ve asked a group of parishioners whether they’ve ever heard a sermon about climate change, and no one raises a hand. So, let’s talk about preaching resilience and cultivating climate justice from the pulpit.

I want to be real. I want to acknowledge right off the bat that it can be hard to preach about climate emergency. Preaching of any kind is challenging but preaching about climate emergency is especially difficult. Why is that? What are we afraid of?1

Maybe we fear being ill-informed (I don’t know enough science).

Maybe we fear provoking division in the congregation (Climate change is too political).

Maybe we fear stressing out our listeners (Daily life is hard enough; why add to their worries?).

Maybe we fear our parishioners won’t be able to handle the bad news (If I do mention climate change, I’d better tone it down and underplay the dire science).

Maybe we fear that climate preaching is not pastoral (People come to church for solace, not to get depressed).

Besides, we may tell ourselves, preaching about climate change should be someone else’s responsibility (Climate change isn’t really “my” issue; someone else should deal with it).

A preacher’s fears may cut close to home (I could lose pledges; I could even lose my job).

And climate preaching may require a painful and very personal reckoning with oneself that the preacher would prefer to avoid (How do I preach resurrection when watching the web of life unravel before my eyes fills me with despair?)

Reckoning with ourselves may also be difficult as we admit our own complicity and consumerism. Years ago, a friend of mine, a suburban priest in a wealthy parish, confessed to me, “How can I preach about climate change when I drive an SUV?”

No wonder so many preachers delay addressing the climate crisis – most of us weren’t trained for this, we don’t want to stir up trouble, and we face an array of fears. As a result, many of us kick the can down the road, perhaps waiting until the lectionary provides the supposedly “perfect” text.

Well, I think it’s fair to say that the time for shyness about preaching on climate change has long since passed. It’s high time for us preachers to overcome our fears and step into the pulpit to preach a bold message of Gospel truth and Gospel hope, because climate change is bearing down on us fast. The winds of war are howling. We live amidst a war against Ukraine that is underwritten by oil and gas, and a relentless war against Earth herself as coal, gas, and oil continue to be extracted and burned. This week the U.N. Secretary General warned that the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius is “on life-support.”2 He went on to say: “Last year alone, global energy-related CO2 emissions grew by 6% to their highest levels in history. Coal emissions have surged to record highs. We are sleepwalking to climate catastrophe. Our planet has already warmed by as much as 1.2 degrees, and we see the devastating consequences everywhere. … If we continue with more of the same, we can kiss 1.5 goodbye. Even 2 degrees may be out of reach.”

So, do we need to preach and practice resilience? You bet we do. Do we need to wake up and quit sleepwalking? You bet we do. For a long time, we may have been sitting on the sidelines, telling ourselves: Things aren’t that bad. The scientists are exaggerating. Or: If I don’t pay attention, it will go away. But eventually our efforts to ignore the reality of a rapidly changing climate can’t help but fall apart. One too many reports of melting glaciers and bleaching coral reefs, one too many accounts of withered fields and bone-dry reservoirs, one too many stories of massive downpours and flash flooding, one too many experiences of devastating wildfires and record heatwaves, and it becomes impossible to suppress awareness of the climate crisis. Our defenses crumble. And we experience what journalist Mark Hertsgaard calls the “Oh, shit” moment we all must have. Climate change is real. It’s here. It’s accelerating.

The truth is that if we keep burning fossil fuels and stick to business as usual, by the end of century, average global temperature will rise 4.2 degrees Celsius (= 7.6 degrees F). Human beings simply can’t adapt to a world that hot.

And let’s not forget that, depending on their social location – on their race and class – people experience ecological breakdown differently. As the saying goes: “We’re all in the same storm, but we’re not in the same boat.” Low-income and low-wealth communities, racial minorities, and the historically underserved are those hurt first and worst by a changing climate, those least able to adapt, and those least likely to have a seat at the table where decisions are made.

Oh, shit.

This is where preachers have an essential role to play. This is where preaching resilience, preaching justice, preaching faithfulness to the crucified and risen Christ becomes crucial. Why? Because the more that people know about the social and ecological breakdown going on worldwide – and the more they experience it directly, in their own lives – the more they may feel overwhelmed, hopeless, or depressed. That’s why a message of urgency needs to be accompanied by a message of agency, a message of empowerment and strength: God is with us, we’re not alone, and there’s a lot we can do.

Here are nine things I try to do when preaching on climate.

- Push back against helplessness

That’s one of the main functions of good climate preaching: push back against helplessness. Your parishioners might not have mentioned it to you, but it’s likely that many of them are grappling with climate anxiety, grief, and dread. A national survey recently conducted by Yale Program on Climate Change Communication reports that seven in ten Americans (70%) say they are at least “somewhat worried” about global warming and that one in three (35%) are “very worried” about it – numbers that have reached a record high.3 It can be a relief when a preacher finally names and addresses their fears, makes climate change “speakable,” and pushes back against the helplessness and “doomism” that suck our spirits dry. That’s why preaching about climate emergency can be deeply pastoral, an act of kindness to your congregation.

Simply gathering for worship can also push back against helplessness: we see each other’s face, we hear each other’s voices, maybe we take each other’s hands. How do people get through tough times? We gather, we sing, we hear our sacred stories, we raise our spirits together. We sense the power of being part of a community that longs, as we do, to create a better world. Entrusting ourselves to God, especially alongside fellow seekers, can overcome our sense of helplessness and release unexpected power among us to do “infinitely more than we can ask or imagine” (Ephesians 3:20).

- Enable people to face hard facts

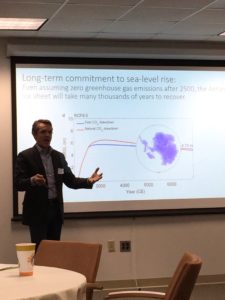

Like all spiritual seekers, Christians are committed to the search for truth, to cutting through fantasy and self-deception. So, in my sermons I share some facts about climate science. As climate preachers we need to know the basics: climate change is real, it’s largely caused by human activity, it’s gotten worse in recent decades, and it will have disastrous effects unless humanity changes course fast. Basic information is available from many sources, such as NASA or reputable environmental groups like Natural Resources Defense Council.4 For up-to-date climate information, I subscribe to daily news from Climate Nexus.5

So – we share some science, but we don’t have to worry that we need to be a scientist. In preaching, I keep my science comments short, brisk, and sober. To summarize the big-picture effects of a changing climate, I often quote a couple of sentences by Bill McKibben from his book, Eaarth: “We’ve changed the planet, changed it in large and fundamental ways… Our old familiar globe is suddenly melting, drying, acidifying, flooding, and burning in ways that no human has ever seen.”6 Then I cite specific examples that resonate most strongly with the local congregation. In California, I mentioned drought, wildfire, and mudslides; on Cape Cod, I mentioned rising and acidifying seas, and threats to fishing and groundwater.

So – we share some science, but we don’t have to worry that we need to be a scientist. In preaching, I keep my science comments short, brisk, and sober. To summarize the big-picture effects of a changing climate, I often quote a couple of sentences by Bill McKibben from his book, Eaarth: “We’ve changed the planet, changed it in large and fundamental ways… Our old familiar globe is suddenly melting, drying, acidifying, flooding, and burning in ways that no human has ever seen.”6 Then I cite specific examples that resonate most strongly with the local congregation. In California, I mentioned drought, wildfire, and mudslides; on Cape Cod, I mentioned rising and acidifying seas, and threats to fishing and groundwater.

When so much misinformation is being spread and funded by fossil fuel corporations and by the politicians in their pockets, faith leaders need to be resolute in speaking hard truths. A religion that directs our gaze to a suffering, dying man on a cross is surely a religion that can face painful facts.

- Offer a positive vision of the future

Climate science has done its job, reporting on the catastrophic effects of burning fossil fuels. But facts aren’t enough to persuade people to take meaningful, concerted action. For that, we need vision – a shared goal and purpose and values. That’s what preachers do: we lift up a vision of people living in just and loving relationships with each other and with the whole Creation, a vision energized by a deep desire for God’s love to be fully manifest in the world.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry observed, “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” How do you build resilience? By lifting up God’s vision of a Beloved Community and by inviting everyone to join God’s mission of reconciling us to God, each other, and the whole Creation. This is the mission that Archbishop Desmond Tutu called the “supreme work” of Jesus Christ.

- Explore ethical questions and provide a moral framework

The climate crisis forces upon us existential questions about the meaning, purpose, and value of human life. What is our moral responsibility to future generations? What does it mean to be human, if human beings are destroying life as it has evolved on this planet? How do we address the anger, self-hatred and guilt that arise with this awareness? Are we willing to radically amend our personal patterns of consumption and waste? What does a “good” life look like, once we know the deadly consequences of over-consumption, inequitable distribution of resources, and being part of an inherently unsustainable, extractive economy that depends on fossil fuels and unlimited growth?

Such questions may hover in the background or roar to the foreground. Congregations provide a context for grappling with these questions, and preachers can offer moral grounding and guidance, reminding their listeners of such old-fashioned values as compassion and generosity, self-control and selfless service, simple living, sacrifice, justice, forgiveness, and non-violent engagement in societal transformation.

- Encourage reconciliation

Climate change has become a deeply divisive political issue – so polarizing that people may fear to mention the subject to family members, co-workers, and friends. Sermons can open a space for conversation, and congregations can follow up by providing settings for difficult conversations and active listening. If we can express compassion while also holding groups and individuals morally accountable, we can create possibilities for reconciliation and collaboration that otherwise might not exist.

Jim Antal points out in his seminal book, Climate Church, Climate World, that “truth and reconciliation” groups could be modeled on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that was formed in South Africa in the 1990’s after the abolition of apartheid. Antal writes: “Initiating Truth and Reconciliation Conversations could well be the most important contribution of the church to creating a world able to undergo the great transition we are now beginning. For many generations we have sought to conquer, dominate, and exploit nature. Now we must seek intergenerational and cross-species atonement. It seems to me that if the church, the synagogue, and the mosque are to offer meaningful hope in the years ahead, they must host such personal and communal, transparent and sacred conversations.”7

- Provide opportunities for emotional response

The climate crisis can make us go numb. Why think about the enormous stretches of coral reefs in Australia that died in less than two months? What can we possibly feel in response to the acidifying ocean, the children choking from asthma in our inner cities, the rising seas, the ever-increasing droughts and floods, and the cascade of species going extinct? It is hard enough to face our own mortality or to mourn a loved one’s death. How do we begin to explore our fear and grief in response to the ecocide going on around us – much less express it? How do we move beyond despair?

Preachers can offer practices, teachings, and rituals that allow us to feel, accept, and integrate the painful emotions evoked by climate change. We can create small circles for eco-grief lament and prayer. And we can hold public ceremonies outdoors. Over the years I’ve led or participated in many outdoor interfaith public liturgies about climate change. Some were held after environmental disasters such as the Gulf of Mexico oil spill and Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines; others were held before significant environmental events, such as Pope Francis’ visit to Washington, D.C., and the U.N. climate talks in Paris. Preachers and congregations can create public spaces for expressing grief, naming hopes, and touching our deep longing for healing and reconciliation. We can protect our human capacity to feel our emotional responses without being overwhelmed. Our emotions can become a source of energy for constructive action to address the emergency.

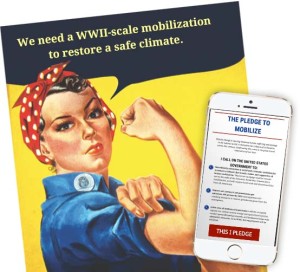

- Build hope by taking action

How do we maintain hope? That’s a question many contributors address in the anthology I co-edited with Leah Schade, Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis. One author, Tim DeChristopher, is a Unitarian Universalist who spent two years in federal prison after disrupting an oil and gas auction in Utah. When someone asks him, “What gives you hope?” Tim replies, “How can anything ‘give’ me hope?” He writes: “Hope is inseparable from our own actions. [Hope] isn’t given; it’s grown. Waiting to act on climate change until we have hope is like waiting to pick up a shovel until we build callouses on our hands. The hope never arrives until we get to work.”8

In my climate sermons I include suggestions for action, such as cutting back sharply on our use of fossil fuels, moving toward a plant-based diet, going solar, protecting forests, and planting trees. Individual actions to reduce our household carbon footprint are essential to our moral integrity and they help to propel social change. Yet the scope and speed of the climate crisis also require engagement in collective action for social transformation. As environmental justice activist, Mary Annaise Heglar, puts it: “I don’t care if you recycle. Stop obsessing over your environmental ‘sins.’ Fight the oil and gas industry instead.”9

In my climate sermons I include suggestions for action, such as cutting back sharply on our use of fossil fuels, moving toward a plant-based diet, going solar, protecting forests, and planting trees. Individual actions to reduce our household carbon footprint are essential to our moral integrity and they help to propel social change. Yet the scope and speed of the climate crisis also require engagement in collective action for social transformation. As environmental justice activist, Mary Annaise Heglar, puts it: “I don’t care if you recycle. Stop obsessing over your environmental ‘sins.’ Fight the oil and gas industry instead.”9

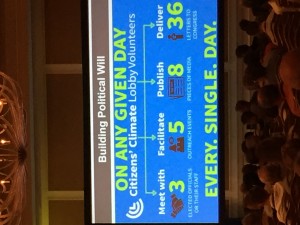

So, in my sermons I encourage parishioners not only to live more lightly on Earth but also to use their voices and votes to make it politically possible to do what is scientifically necessary. We can support the growing movement to push banks to stop financing fossil fuel projects. We can lobby for policies that support renewable energy, clean green jobs, and a just transition that addresses the needs of poor and low-wealth communities and communities of color, and the needs of workers in the fossil fuel industries as we transition to a clean energy economy. If we have financial investments, we can divest from fossil fuels. If we’re college graduates, we can push our alma mater to divest. We can support 350.org, ThirdAct.org (a new climate action group led by Bill McKibben for people over 60), Sunrise Movement (a climate action group led by people under 30), Extinction Rebellion, and other grassroots efforts to turn the tide. We can put our bodies on the line and risk arrest in non-violent resistance to fossil fuels. By inspiring significant action, preachers can challenge the deathly status quo of “business as usual” and rouse society out of apathy and inaction.

- Deepen reverence for nature

Our society treats the natural world as an object to master, dominate, and exploit, and preachers can call us to reclaim the sacredness of Earth. After all, nature is a place where humans have always encountered God – so say generations of mystics and theologians, including Moses, Jesus, and St. Paul (Romans 1:20). As poet Gerard Manley Hopkins puts it, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.” Destroying Earth is therefore a desecration, a sin against the Creator.

So, in addition to preaching reverence for God’s creation, maybe we can plant a community garden in the vacant lot behind our church. Maybe we can support land trusts to preserve farms, woods, and open space; maybe we can partner with organizations to bring inner-city children into natural settings; maybe we can sponsor retreats, hikes, and worship services that explore the wonders of Creation. Step by step we can begin to reclaim what traditional indigenous societies have never forgotten: the land itself is sacred. Discovering this for ourselves will affect our behavior: we only fight to save what we love.

Which brings me to my final aim in preaching:

- Encourage love

Cultivate love. That really should be Point #1! Whenever I preach, I try to evoke the presence of a God who loves us beyond measure, a God who heals and redeems, who liberates and forgives. I preach about a God who honors and shares our climate grief, a God who weeps with us. I preach about a God who understands our outrage, fear, and sorrow as the living world around us is destroyed; a God, in the words of Peter Sawtell, who calls us “to active resistance, not to quiet acceptance.”10 I preach about a God who knows our guilt and complicity in that destruction and who gives us power to amend our lives. I preach about a God who longs to create a Beloved Community that includes all beings, not just human beings. I preach about a God who sets us free from the fear of death and who gives us strength to bear witness to a love that nothing can destroy. When people are going mad with hatred and fear, only love can restore us to sanity.

When we deliver a strong climate sermon and we trust in the power of the Holy Spirit, we’re like the boy in the story of Jesus feeding the five thousand (Jn. 6:1-14): we put our words in Jesus’ hands. Through his grace and power, maybe our small offering will become a catalyst that enables a crowd to be fed. Maybe our words, like those of Ezekiel, will be infused with Spirit-power to enliven that valley of dead, dry bones and breathe life into a multitude (Ez. 37:1-14). Maybe that homily – that word of challenge or encouragement – will contribute to a social tipping point that releases rapid societal transformation.

Holy Week, Easter, and Earth Day are all approaching, and this year we have a special opportunity to amplify the power of our witness: we can register our climate sermons and prayer vigils with GreenFaith’s global initiative, Sacred Season for Climate Justice. All five of the world’s major religions celebrate a holy day or season between now and early May, and faith communities around the world will hold special events and services that proclaim one urgent message: climate justice now! So, when you preach a climate justice/climate resilience sermon sometime this month, as I hope you will, please be sure to register your service with Sacred Season for Climate Justice.11

Thank you, friends.

___________________________________________________________________________

The Rev. Dr. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas is an Episcopal priest, author, retreat leader, and climate activist. She has been a lead organizer of many Christian and interfaith events about care for Earth, and she leads spiritual retreats in the U.S.A. and Canada on spiritual resilience and resistance in the midst of a climate emergency. Her latest book, Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (2019) is a co-edited anthology of essays by religious environmental activists. She has been arrested in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere to protest expanded use of fossil fuels. She serves as Missioner for Creation Care in the Episcopal Diocese of Western Mass. and Southern New England Conference, United Church of Christ, and as Creation Care Advisor for the Episcopal Diocese of Mass. Her Website, RevivingCreation.org, includes blog posts, sermons, videos, and articles.

Selected resources for climate-crisis preaching are available on her website, as are about 100 of her lectionary-based sermons on climate change.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. This section is drawn from “Preaching When Life Depends on It: Climate Crisis and Gospel Hope,” by Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, Anglican Theological Review (Spring, 2021, Vol. 103, 2), 208–219, https://revivingcreation.org/preaching-when-life-depends-on-it-climate-crisis-and-gospel-hope/

3. Leiserowitz A. et al, Climate Change in the American Mind, September 2021. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, November 18, 2021.

4. https://climate.nasa.gov/resources/global-warming-vs-climate-change/

https://www.nrdc.org/stories/global-climate-change-what-you-need-know/

5. To sign up, send an email to: info@climatenexus.org.

6. Bill McKibben, Eaarth (New York: Times Books, Henry Holt & Co., 2010) xiii, book jacket. The title is deliberately mis-spelled in order to signal that the planet onto which you and I were born is not the same planet we inhabit today.

7. Jim Antal, Climate Church, Climate World: How People of Faith Must Work for Change (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), 77.

8. Tim DeChristopher, “Working Up Hope,” in Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis, ed. Leah Schade and Margaret Bullitt-Jonas (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 148.

9. Mary Annaise Heglar, “I work in the environmental movement. I don’t care if you recycle. Stop obsessing over your environmental ‘sins.’ Fight the oil and gas industry instead.” (Vox, June 4, 2019)

10. Peter Sawtell, “Three Layers of Environmental Preaching,” http://www.eco-justice.org/3layers.asp/. (If the link doesn’t work, you can search for the article directly.)

11. Creation Justice Ministries has also produced an Earth Day resource for 2022, “Weathering the Storm: Faithful Climate Resilience,” a timely and applicable resource for all of 2022.

The climate crisis can make us go numb. Why think about the enormous stretches of coral reefs in Australia that just died in less than two months? What can we possibly feel in response to the acidifying ocean, the children choking from asthma in our inner cities, the rising seas, the ever-increasing droughts and floods, and the cascade of species going extinct?

The climate crisis can make us go numb. Why think about the enormous stretches of coral reefs in Australia that just died in less than two months? What can we possibly feel in response to the acidifying ocean, the children choking from asthma in our inner cities, the rising seas, the ever-increasing droughts and floods, and the cascade of species going extinct? Faith communities can model best practices for “going green,” such as to get an energy audit, increase energy conservation and efficiency, look into installing solar panels, put in bike racks, replace lawns with community gardens, and so on. But taking care of our immediate buildings and community is just a start. An adequate response to the scope and speed of the climate crisis requires collective action and political engagement.

Faith communities can model best practices for “going green,” such as to get an energy audit, increase energy conservation and efficiency, look into installing solar panels, put in bike racks, replace lawns with community gardens, and so on. But taking care of our immediate buildings and community is just a start. An adequate response to the scope and speed of the climate crisis requires collective action and political engagement.