The Rev. Dr. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas preached on April 15, 2018 at Federated Church of Orleans, on Cape Cod, Massachusetts: “You are witnesses of these things.”

Author Archives: mbj

“You are witnesses of these things”

Today we are deep into the Great Fifty Days of Easter, and I want to share a story told by an Episcopal bishop about leading worship one Easter morning. Bishop Mark Macdonald was preaching to a congregation in the middle of Navajo Nation. When the time came to read the Gospel account of Jesus’ resurrection, Bishop Macdonald stood up and began reading in Navajo: “It was early in the morning…” Almost before the words were out of his mouth, “the oldest person there, an elder who understood no English, said loudly (in Navajo), ‘Yes!’”

1. Mark Macdonald, “Finding Communion with Creation,” in Holy Ground: A Gathering of Voices on Caring for Creation, edited by Lyndsay Moseley and the staff of Sierra Club Books, San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 2008, pp. 150-151. Macdonald is the former bishop of Alaska, and now serves as the National Indigenous Bishop of the Anglican Church of Canada. 2. Ibid, p. 151. 3. “Mystic Christ,” by Fr. John Giuliani, Bridge Building Images, Inc.

We carried out Exodus from Fossil Fuel: An Interfaith Witness for Climate Action at the Massachusetts Statehouse on Monday in Holy Week, shortly before Passover, on March 26, 2018. Deep thanks to Andrew Mudge of Blackkettle Films, who donated his time and skills to make this inspiring 4-minute video.

Click here to watch the video on YouTube.

Hot off the presses! Margaret contributed an essay to a collection of essays published in Spring 2018 by SEARCH: A Church of Ireland Journal, on the topic: The Episcopal Church — Standing Up to Climate Change Denial.

Margaret contributed to a collection of essays, “The Episcopal Church — standing up to climate change denial?”, assembled by Margaret Daly Denton and published in SEARCH: A Church of Ireland Journal, Spring 2018. The other contributors are Presiding Bishop Michael B. Curry, the Rev. Fletcher Harper (GreenFaith), and Nathan Empsall (Yale Divinity School seminarian).

To download the essay, click on the title: TEC Standing up to Climate Change Denial.

The Website for SEARCH: A Church of Ireland Journal is here.

On a bright, wind-swept day shortly before Easter and Passover, a crowd of faith leaders and members of faith communities gathered on the steps of the Massachusetts State House to call upon Governor Baker to take bold leadership in addressing climate disruption. Drawing from the ancient stories of Moses confronting Pharaoh and of Jesus confronting the imperial powers of Rome, “Exodus from Fossil Fuel” celebrated our shared determination, as people of diverse faiths, to set ourselves free from fossil fuels and to create a more just and sustainable society.

Before we created and carried out this public event, eighteen faith leaders representing a range of religious traditions – including the Commonwealth’s top leaders of the Episcopal Church, United Methodist Church, and United Church of Christ – signed a letter to Governor Baker. In our letter, we expressed our conviction that we have a spiritual and moral obligation to protect the web of life. We appealed to the Governor to meet with a small group of faith leaders, so that we could discuss the values that lead us to oppose construction of all new fossil fuel infrastructure in the Commonwealth.

We heard not a word in response.

Hence, on March 26, Monday in Holy Week and a few days before Passover, we went ahead with our public protest and appeal. As I said in my remarks to the press, “We are holding this event during a time of year that is a holy season for multiple faith traditions, because protecting our climate and God’s creation is one of the most important ways to practice our faith in today’s world.”

The lively outdoor service included songs and prayers; a moving litany of “climate plagues” and public mourning led by two rabbis; and speakers representing front-line communities from all across the Commonwealth that are resisting new fracked gas pipelines with vigils, protests, and non-violent civil disobedience. After a closing blessing and song, we walked in procession to the State House, led by the drumbeats and chants of a small group of Buddhist monks. At the doorway to Governor Baker’s office, a few of us spoke with his staff members. Meanwhile the crowd filled the hallway, writing postcards to the Governor, holding palm branches aloft, and singing songs of hope. Then we scattered in every direction, heading to the offices of our state representatives and senators to advocate for the Senate’s clean energy omnibus bill (S. 2302) and the House’s environmental justice act (H. 2913).

Astonishing news arrived the next day: the judge in the trial of the final 13 defendants who had carried out civil disobedience to protest the West Roxbury Lateral fracked gas pipeline were found not guilty, reportedly because their actions were deemed a “necessity.” If confirmed, this could be the first time that defendants were acquitted based on “climate necessity.” Since I was one of the 198 people arrested for carrying out civil disobedience at the site of this high-pressure, dangerous pipeline, I feel particular joy in celebrating the judge’s historic decision.

-

- The Berkshire Edge wrote a good short article about Exodus from Fossil Fuel that can be found here.

- The entire worship service (except for improvised statements that have yet to be transcribed) can be found here. We hope you will use this document to stimulate your own thinking about how to create an interfaith worship service that lifts up the urgency of combating climate change. Please let us know what you come up with! We also hope that, in reviewing this service, you will be inspired by the range and depth of active resistance to fracked gas pipelines that is now being carried out across the Commonwealth.

- Do you wish to express your own commitment? Clergy and religious leaders are invited to sign a statement calling for moral leadership for climate justice. The Clergy Climate Action statement includes a pledge to resist new fossil fuel development through nonviolent direct action. Congregants and community members can also add their support.

Below is the blessing that I delivered at the end of the service:

We’ve shared a lot of words, so, before we pray, I invite us to take a moment in silence to feel the good earth that supports our feet, which we bless with every step and which blesses us with every step… I invite us to take a good deep breath of air, giving thanks for the trees and green things, giving us oxygen…and to feel that warm sun with all its good energy, with which we can power so many things…

We’ve shared a lot of words, so, before we pray, I invite us to take a moment in silence to feel the good earth that supports our feet, which we bless with every step and which blesses us with every step… I invite us to take a good deep breath of air, giving thanks for the trees and green things, giving us oxygen…and to feel that warm sun with all its good energy, with which we can power so many things…

I invite you to join me in a spirit of prayer as we turn to our Creator, the Higher Power, the holy Mystery, the Great Spirit whom we know by many names:

God of abundance, we stand before you with grateful hearts, thankful for the gift of life, thankful for this beautiful world that you entrusted to our care. Thank you for sending into our midst these warriors and prophets who are giving themselves to the struggle to preserve a habitable world! We ask you to bless them and protect them. Give them courage when they are afraid, strength when they falter, and comfort when they grieve. Sustain them with your bountiful Spirit and guide them on their sacred path.

We ask your blessing on every one of us here. Thank you for the love that drew us here today, for the love that wells up from the center of our being, abides in our midst, and reaches out in every direction, calling us to recognize each other and all other beings as kin. Help us to bear witness to that love in everything we say and do.

We ask you to bless our Governor, our legislators, our political leaders, and all in authority, to turn their hearts and to guide them to make wise decisions that serve the common good.

And we ask you to bless our efforts going forward. Make us bold and humble, fierce and tender in our search for justice, healing, and peace. Amen.

Photo: Faith leaders preparing to lead Exodus from Fossil Fuel in front of the State House

(l. to r.) Rev. Fred Small (Minister for Climate Justice, Arlington Street Church, Boston); Rev. Betsy Sowers (Minister for Earth Justice, Old Cambridge Baptist Church); Rev. Dr. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas (Missioner for Creation Care, Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts & Massachusetts Conference, United Church of Christ); Rev. Ian Mevorach (Spiritual Leader, Common Street Spiritual Center in Natick; Coordinator, American Baptist Churches Creation Justice Network); Rev. Dr. Lawrence Jay (Executive Director, Rolling Ridge Retreat and Conference Center of the New England United Methodist Conference); Kristina Keefe-Perry (Coordinator, Creation Care Ministries, The American Baptist Churches of Mass.); Rabbi Katy Z. Allen (President, Jewish Climate Action Network)

Deep thanks to Andrew Mudge of Blackkettle Films, who donated his time and skills to make this inspiring 4-minute video of Exodus from Fossil Fuel, which is now posted on YouTube.

Easter power

I am blessed to be with you on this holy night as we immerse ourselves in the story of our salvation, the story of God’s love affair with the whole creation. In story after story, we have touched the great truth that we’ve been loved since the beginning of time, that God has led us safely through the Red Sea, guided us through the wilderness, walked with us into the darkness, shared our suffering and pain, and even now is shining a pure light within us and among us.

Through the power of resurrection, a great energy has been released into the world, and that power is already at work within us. It springs to new life when we gather to resist the forces of destruction, when we stand up for gun safety or engage in peaceful civil disobedience to stop new fracked gas pipelines. It springs to new life when we gather around the table to break bread in Jesus’ name. It springs to new life when we speak words that are truthful and kind, and when we treat ourselves and one another with compassion and respect. It springs to new life when we refuse to abandon and abuse Mother Earth and when we search for ways to re-weave the web of life.

It’s not enough just to gaze on Christ’s resurrection from afar. This is not only Jesus’ miracle – it is our miracle, too, a miracle that each of us is invited to experience more deeply every day of our lives.

Tonight, in silence, words, and song, in fear and wonder, we welcome into our lives and into our wounded and lovely world the Risen Christ and the power of resurrection.

Jesus Christ has risen to new life, and so have we.

Alleluia! Christ is Risen! The Lord is Risen, indeed! Alleluia!

Through the power of resurrection, a great energy has been released into the world, and that power is already at work within us. It springs to new life when we gather to resist the forces of destruction, when we stand up for gun safety or engage in peaceful civil disobedience to stop new fracked gas pipelines. It springs to new life when we gather around the table to break bread in Jesus’ name. It springs to new life when we speak words that are truthful and kind, and when we treat ourselves and one another with compassion and respect. It springs to new life when we refuse to abandon and abuse Mother Earth and when we search for ways to re-weave the web of life.

It’s not enough just to gaze on Christ’s resurrection from afar. This is not only Jesus’ miracle – it is our miracle, too, a miracle that each of us is invited to experience more deeply every day of our lives.

Tonight, in silence, words, and song, in fear and wonder, we welcome into our lives and into our wounded and lovely world the Risen Christ and the power of resurrection.

Jesus Christ has risen to new life, and so have we.

Alleluia! Christ is Risen! The Lord is Risen, indeed! Alleluia!

Keep the faith

What a blessing to be with you this morning! Thank you, Steve, for welcoming me back to this pulpit. I’m an Episcopal priest and long-time climate activist, and I have the world’s longest job title. I work as Missioner for Creation Care in the Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts, and the United Church of Christ in Massachusetts. I am not a “missionary,” a word that’s often associated with trying to convert someone, but a “missioner,” which means someone who has been sent out on a mission, someone who has been sent out to serve God beyond the boundaries of a building. As Missioner for Creation Care, I travel in and beyond Massachusetts, preaching and speaking and leading retreats about the sacredness of God’s Creation and our call to become faithful stewards of God’s good Earth, particularly our call to address climate change. The God whom we meet so intimately in our depths is the same God who sends us out into the world to be healers and justice-seekers. My Website is RevivingCreation.org, where you can read articles and sign up for blog posts.

My sermon boils down to three words: Keep the faith. That’s the phrase I often find myself saying to friends as we prepare to go our separate ways: Keep the faith. Other people have other favorite go-to phrases when they say goodbye. I remember Walter Cronkite signing off at the end of every nightly newscast: “That’s the way it is.” Before him there was Edward R. Murrow, who ended his radio and TV broadcasts with the words, “Good night, and good luck.” And as long as we’re on the subject of television, let’s not forget Dr. Spock from Star Trek, with his farewell blessing, “Live long and prosper.” I like all these expressions, but what I want to say, what I want to hear, is “Keep the faith.” We live in a precarious time, a time of turmoil when for all kinds of reasons many of us feel rattled and anxious, and brace ourselves for the next bit of bad news. So how glad I am that today, on the Second Sunday in Lent, we are invited to remember Abraham, our brother in the faith, our father in the faith, “the father of all of us,” as St. Paul puts it in his Letter to the Romans (Romans 4:16). When the story begins, Abraham is the archetype of someone stuck in a hopeless place, a place without faith. He is ninety-nine years old, for heaven’s sake, his body “already as good as dead,” according to St. Paul (Romans 4:19). He has no children by his wife, Sarah, who is no spring chicken, either. The data would suggest that he has reached a dead end. This man who wished for progeny for so long is all washed up; he’s at the end of his rope; his future is barren; the door has closed.

But then he has an encounter with God that changes everything. We don’t hear the details of that encounter in today’s reading, though in another passage from Genesis it seems that Abraham’s experience took place at night, in the desert, under the stars (Genesis 15:5). Abraham encounters a God of life, a creative God with the power to make all things new, a God, says St. Paul, “who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Romans 4:17).

This wild and life-giving God, a God of justice and mercy, makes a covenant with Abraham, an unshakable bond, and promises him offspring, and a good land, and a future. None of those promises are visible yet, none of them has yet come to be, but Abraham’s faith awakens. It comes alive: he puts his faith in God. He trusts in God’s presence; he trusts in God’s power. He casts his lot with a God of infinite love and creativity, a God who has the power to restore and make whole. And in response to God’s call, Abraham sets out in faith.

I like all these expressions, but what I want to say, what I want to hear, is “Keep the faith.” We live in a precarious time, a time of turmoil when for all kinds of reasons many of us feel rattled and anxious, and brace ourselves for the next bit of bad news. So how glad I am that today, on the Second Sunday in Lent, we are invited to remember Abraham, our brother in the faith, our father in the faith, “the father of all of us,” as St. Paul puts it in his Letter to the Romans (Romans 4:16). When the story begins, Abraham is the archetype of someone stuck in a hopeless place, a place without faith. He is ninety-nine years old, for heaven’s sake, his body “already as good as dead,” according to St. Paul (Romans 4:19). He has no children by his wife, Sarah, who is no spring chicken, either. The data would suggest that he has reached a dead end. This man who wished for progeny for so long is all washed up; he’s at the end of his rope; his future is barren; the door has closed.

But then he has an encounter with God that changes everything. We don’t hear the details of that encounter in today’s reading, though in another passage from Genesis it seems that Abraham’s experience took place at night, in the desert, under the stars (Genesis 15:5). Abraham encounters a God of life, a creative God with the power to make all things new, a God, says St. Paul, “who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Romans 4:17).

This wild and life-giving God, a God of justice and mercy, makes a covenant with Abraham, an unshakable bond, and promises him offspring, and a good land, and a future. None of those promises are visible yet, none of them has yet come to be, but Abraham’s faith awakens. It comes alive: he puts his faith in God. He trusts in God’s presence; he trusts in God’s power. He casts his lot with a God of infinite love and creativity, a God who has the power to restore and make whole. And in response to God’s call, Abraham sets out in faith. I want to emphasize that last point: he sets out. He walks. Today’s first reading makes it clear that faith is active, not passive: faith is practiced and made manifest in action. What does God say to Abraham? “I am God Almighty; walk before me, and be blameless.” Walk – don’t stand still, don’t get passive, don’t stay stuck and hopeless. Don’t wait for someone else to do something. Get going. Get moving. Take action.

And don’t walk alone. “Walk before me,” says Yahweh, “and be blameless.” It is if God were an unseen presence and power that is always behind us, as if our job were to clear the way for divine love to move through us, freely and fully, like a river that flows through us and out into the world, so that all people and all beings can be blessed and healed and reconciled. Our task in the course of a day is to stay in conscious contact with God, so that as far as possible we are walking before God, not walking alone, not being driven by our ego or by our anxiety. Activists usually depend on people power, but spiritual activists – people who walk in faith – depend on God-power. It is God who energizes and emboldens us, God who gives us power to do more than we can ask or imagine.

We live in a time that cries out for the imagination, determination, and heart of people of faith. The web of life is unraveling before our eyes. Great populations of creatures – even entire species – are rapidly disappearing from Earth. Scientists tell us that a mass extinction event is now underway – what they’re calling a “biological annihilation.” In addition to species extinction, we also face a changing climate. Because of the relentless burning of fossil fuels, month after month our planet is breaking records for heat. As Bill McKibben wrote, “Our old familiar globe is suddenly melting, drying, acidifying, flooding, and burning in ways that no human has ever seen.” 1 To cite just one example of how burning fossil fuels is affecting our planet: a recent study examined all the major research on oxygen loss in the ocean and concluded that over the past fifty years the amount of water in the open ocean that is without oxygen has more than quadrupled. As one headline puts it, the ocean is losing its breath. To put it another way, the ocean is suffocating. Lest we imagine that land creatures will not be affected, one scientist points out that about half of the oxygen on Earth comes from the ocean. A professor of marine science who reviewed the study commented that the need for action was best summarized by the motto of the American Lung Association: “If you can’t breathe, nothing else matters.” I suppose that’s one reason I’m a climate activist: I like to breathe.

Climate change is not one of 26 different causes that we care about, but a cause that affects everything we cherish. If you care about the poor, you care about climate; if you care about immigration and refugees, you care about climate; if you care about public health, you care about climate; if you care about human rights, you care about climate; if you care about loving God and your neighbor, you care about climate. Climate justice is not an issue for a special interest group. If you like to breathe, if you like to eat, if you’d like to leave your children a world they can live in, you care about climate.

To heal God’s Creation, there is a great deal that we, as individuals, can do. Maybe we can plant a tree. Save a tree. Recycle more. Drive less. Eat local, eat organic, eat less meat and move to a plant-based diet. Maybe we can support local land trusts and non-profits focused on conservation. We can fly less – and, if we must fly, buy carbon offsets. Maybe we can afford solar panels and move toward a carbon-neutral home. If we have investments, we can divest from fossil fuels, and if we’re college graduates, we can urge our alma mater to divest.

Individual changes make a difference, but because of the scope and speed of the climate crisis, we need more than individual action – we need systemic change. To do that, we will have to confront the powers that be, especially when multinational corporations and members of our own government seem intent on desecrating every last inch of God’s Creation, pillaging every last natural resource, destroying every last habitat, and abandoning every last regulation, rule, and treaty that preserve clean air and water and maintain the stability of our global climate. Under the circumstances, I wonder at what point the practice of carrying out acts of civil disobedience will become as normative for faithful Christians as the practice of prayer.2

We will also have to confront versions of Christianity that contend that God has given us license to pillage and destroy the natural world, as if everything on God’s green Earth were placed here solely for the pleasure and benefit of a single species, Homo sapiens, or at least its privileged elite. Scott Pruitt, head of the Environmental Protection Agency, revealed this week, in an interview with the Christian Broadcasting Network, that he believes that the Bible gives human beings the (quote-unquote) “responsibility” to “harvest” natural resources like coal and oil, although we know full well that burning these fuels is wrecking the planet entrusted to our care. As Mother Jones reports in its cover profile of Pruitt in its March/April issue, the EPA chief’s beliefs are rooted in a version of Christianity that is the “polar opposite from that of other religious leaders, including Pope Francis, who interpret stewardship as the responsibility humans have to protect God’s creation.”

When corporate and political powers set us on a path of disaster – when they remain hell-bent on locating, extracting, and burning as much coal, gas and oil as they possibly can, never mind the potentially catastrophic effects of what they’re doing – the time has come for us to unleash our faith, to make it visible and make it bold.

I give thanks for the story of God’s covenant with Abraham, our father in the faith. It reminds me that in perilous times, God calls forth a people who put their trust in a power greater than themselves; a people who start walking even if they have no map and must create the map as they go; a people with the God-given imagination to envision a future in which the land will prosper and our offspring will thrive; a people who trust in the creative, liberating power of the God who is within them and among them, beyond them and behind them, making a way where there is no way, giving life to the dead, and calling into existence the things that do not exist.

Thank you for whatever you are doing – or will do – to re-weave the web of life and to love God and all our neighbors, human and other-than-human. You know, we are all missioners for Creation care. Every who shares the faith of Abraham and Sarah, everyone who follows Jesus – every one of us here is a missioner for Creation care. Thank you for being on the journey with me.

Keep the faith.

I want to emphasize that last point: he sets out. He walks. Today’s first reading makes it clear that faith is active, not passive: faith is practiced and made manifest in action. What does God say to Abraham? “I am God Almighty; walk before me, and be blameless.” Walk – don’t stand still, don’t get passive, don’t stay stuck and hopeless. Don’t wait for someone else to do something. Get going. Get moving. Take action.

And don’t walk alone. “Walk before me,” says Yahweh, “and be blameless.” It is if God were an unseen presence and power that is always behind us, as if our job were to clear the way for divine love to move through us, freely and fully, like a river that flows through us and out into the world, so that all people and all beings can be blessed and healed and reconciled. Our task in the course of a day is to stay in conscious contact with God, so that as far as possible we are walking before God, not walking alone, not being driven by our ego or by our anxiety. Activists usually depend on people power, but spiritual activists – people who walk in faith – depend on God-power. It is God who energizes and emboldens us, God who gives us power to do more than we can ask or imagine.

We live in a time that cries out for the imagination, determination, and heart of people of faith. The web of life is unraveling before our eyes. Great populations of creatures – even entire species – are rapidly disappearing from Earth. Scientists tell us that a mass extinction event is now underway – what they’re calling a “biological annihilation.” In addition to species extinction, we also face a changing climate. Because of the relentless burning of fossil fuels, month after month our planet is breaking records for heat. As Bill McKibben wrote, “Our old familiar globe is suddenly melting, drying, acidifying, flooding, and burning in ways that no human has ever seen.” 1 To cite just one example of how burning fossil fuels is affecting our planet: a recent study examined all the major research on oxygen loss in the ocean and concluded that over the past fifty years the amount of water in the open ocean that is without oxygen has more than quadrupled. As one headline puts it, the ocean is losing its breath. To put it another way, the ocean is suffocating. Lest we imagine that land creatures will not be affected, one scientist points out that about half of the oxygen on Earth comes from the ocean. A professor of marine science who reviewed the study commented that the need for action was best summarized by the motto of the American Lung Association: “If you can’t breathe, nothing else matters.” I suppose that’s one reason I’m a climate activist: I like to breathe.

Climate change is not one of 26 different causes that we care about, but a cause that affects everything we cherish. If you care about the poor, you care about climate; if you care about immigration and refugees, you care about climate; if you care about public health, you care about climate; if you care about human rights, you care about climate; if you care about loving God and your neighbor, you care about climate. Climate justice is not an issue for a special interest group. If you like to breathe, if you like to eat, if you’d like to leave your children a world they can live in, you care about climate.

To heal God’s Creation, there is a great deal that we, as individuals, can do. Maybe we can plant a tree. Save a tree. Recycle more. Drive less. Eat local, eat organic, eat less meat and move to a plant-based diet. Maybe we can support local land trusts and non-profits focused on conservation. We can fly less – and, if we must fly, buy carbon offsets. Maybe we can afford solar panels and move toward a carbon-neutral home. If we have investments, we can divest from fossil fuels, and if we’re college graduates, we can urge our alma mater to divest.

Individual changes make a difference, but because of the scope and speed of the climate crisis, we need more than individual action – we need systemic change. To do that, we will have to confront the powers that be, especially when multinational corporations and members of our own government seem intent on desecrating every last inch of God’s Creation, pillaging every last natural resource, destroying every last habitat, and abandoning every last regulation, rule, and treaty that preserve clean air and water and maintain the stability of our global climate. Under the circumstances, I wonder at what point the practice of carrying out acts of civil disobedience will become as normative for faithful Christians as the practice of prayer.2

We will also have to confront versions of Christianity that contend that God has given us license to pillage and destroy the natural world, as if everything on God’s green Earth were placed here solely for the pleasure and benefit of a single species, Homo sapiens, or at least its privileged elite. Scott Pruitt, head of the Environmental Protection Agency, revealed this week, in an interview with the Christian Broadcasting Network, that he believes that the Bible gives human beings the (quote-unquote) “responsibility” to “harvest” natural resources like coal and oil, although we know full well that burning these fuels is wrecking the planet entrusted to our care. As Mother Jones reports in its cover profile of Pruitt in its March/April issue, the EPA chief’s beliefs are rooted in a version of Christianity that is the “polar opposite from that of other religious leaders, including Pope Francis, who interpret stewardship as the responsibility humans have to protect God’s creation.”

When corporate and political powers set us on a path of disaster – when they remain hell-bent on locating, extracting, and burning as much coal, gas and oil as they possibly can, never mind the potentially catastrophic effects of what they’re doing – the time has come for us to unleash our faith, to make it visible and make it bold.

I give thanks for the story of God’s covenant with Abraham, our father in the faith. It reminds me that in perilous times, God calls forth a people who put their trust in a power greater than themselves; a people who start walking even if they have no map and must create the map as they go; a people with the God-given imagination to envision a future in which the land will prosper and our offspring will thrive; a people who trust in the creative, liberating power of the God who is within them and among them, beyond them and behind them, making a way where there is no way, giving life to the dead, and calling into existence the things that do not exist.

Thank you for whatever you are doing – or will do – to re-weave the web of life and to love God and all our neighbors, human and other-than-human. You know, we are all missioners for Creation care. Every who shares the faith of Abraham and Sarah, everyone who follows Jesus – every one of us here is a missioner for Creation care. Thank you for being on the journey with me.

Keep the faith.

1. Bill McKibben, Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet, New York: Henry Holt and Company, Times Book, 2010, p. xiii and book jacket. Italics in original. 2. I credit the Rev. Dr. Jim Antal with issuing this challenge, which he explores in his new book, Climate Church, Climate World (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018).

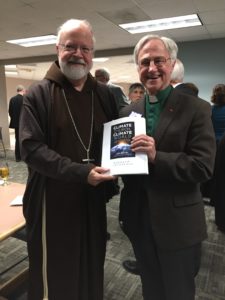

The Archdiocese of Boston hosted an extraordinary conversation on February 8-9, 2018, as leaders drawn from religious and scientific communities gathered to discuss the possibility of forging a partnership to push for decisive action on climate change. The idea for gathering the group came from Phil Duffy, President of the Woods Hole Research Center, who, as Cardinal Sean O’Malley explains in a blog post, “[reached] out to the archdiocese through the good offices of Professor Mark Silk, director of the Greenberg Center for the Study of Religion in Public Life at Trinity College in Hartford.”

Over the years, science and religion have had a complicated and sometimes hostile relationship. As our convener Professor Mark Silk observed, religion and science have distinct approaches to reality. Although scientists sometimes serve as advisers and consultants to religious leaders, and although scientists may turn to religion for inspiration, to form a coalition of religious leaders and scientists “would be something new under the sun.”

Such a partnership has enormous potential in this perilous time. In fact, such a partnership may be not just desirable, but even essential. Given the massive disruption of our global climate that is now underway, we need to hear from scientists, who have made it abundantly clear that continuing to burn fossil fuels will lead in a very short time to climate catastrophe. And we also need to hear from spiritual and religious leaders, who can give us the inspiration, motivation, and moral courage to change course and to create a more just and life-sustaining society.

Phil Duffy contended in his opening remarks that when it comes to addressing climate change, in many ways we already have what we need. “We can do the science,” he said. “We know more than enough to take strong action. We have most of the solutions we need, and we know how to design policies to apply those solutions.” The problem, he said, is that we’re just not doing it. We’re not taking the actions we need to take. “We need to summon the political will.” The only way to do so, he said, is to bring together head and heart. He cited retired Congressman Bob Inglis, a conservative Republican from South Carolina, who wrote, “Climate science can fill our heads, but it can’t change our hearts. Only grace can do that. People of faith are therefore essential if we are to rise to the protection of our common home.”

Professor Silk put it like this: “If a coalition of scientists and faith leaders can’t communicate what is necessary to do, no one can. If no one can communicate what is necessary, no one can do what is necessary.”

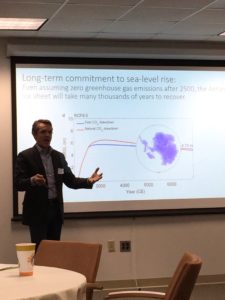

Professor Robert DeConto of University of Massachusetts, Amherst, gave a brief, stark presentation of his research on the Antarctica ice sheet, noting that business as usual would result in a one meter global rise in sea levels by 2100 that would affect 152 million people worldwide – just from the melting of Antarctica’s ice. Lest those numbers sound abstract, he brought his message home with a slide depicting how much of Boston would be underwater.

I was invited to speak about the current state of religious climate action in Massachusetts, and my remarks are posted below. Some of the other faith-based speakers included the Rev. Mariama White-Hammond of Bethel AME Church, who, in a talk entitled “The Cry of the Poor,” spoke eloquently about climate justice, urging us to grapple with the contradiction that the people most harmed by climate change are not the people who make policy decisions.

The Rev. Dr. Jim Antal, whose new book Climate Church, Climate World is about to be released, pressed the religious leaders in the room to recognize that witnessing for God’s Creation is the vocation of the church, the synagogue, the mosque and the temple. “What if taking action on climate were to become as defining a quality of what it means to be religious, as prayer? What if religious leaders in Massachusetts gave at least as much attention to collective salvation as they currently give to personal salvation? What if every person of faith understood that ‘To be a person of faith, I have to speak up for Creation?’”

Discussion was lively. We shared insights, ideas, and hopes. To cite just a couple of comments, Bill Moomaw, Professor Emeritus of International Environmental Policy at the Fletcher School, Tufts University, reminded us that in November 2017, world scientists released a warning to humanity about the daunting environmental challenges that we face and the urgent need to work together as a human race to create a sustainable and livable future. It is, in fact, a second notice, coming 25 years after a manifesto published in 1992. (See also: “16,000 scientists sign dire warning to humanity over health of planet”)

Professor Moomaw suggested: What if this second notice about the ways that human activity is unraveling the web of life were handed out in every congregation and cited in the newsletters of every faith community?

The Rev. Fred Small, Minister for Climate Justice at Arlington Street Church, Boston, stood up to say, “This is a historic gathering. If it isn’t a historic gathering, we will have failed.” He urged us to take to heart Pope Francis’ admonition in Laudato Si that we must become politically engaged and strategic. To quote the Pope’s encyclical: “Unless citizens control political power – national, regional and municipal – it will not be possible to control damage to the environment.” (179).

Rev. Fred went on to say, “My prayer and my entreaty to the Archdiocese is to bring the same passion and priority to climate justice as to any pro-life effort heretofore — because there is nothing more pro-life than protecting and preserving Creation, the environment on which all human life depends.” If we don’t do this, he added, the cost would be enormous in fire, famine, flood, and refugees.

Looking back on these intensive two days of discussion and our plans for next steps, I live in hope that something new is indeed being born right here in Massachusetts as people of science and people of faith come together to unite head and heart and to work together to protect our common home.

My thoughts are expressed in the words of the prophet Isaiah, who heard God saying,

“I am about to do a new thing;

now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?

I will make a way in the wilderness

and rivers in the desert.” (Isaiah 43:16)

Here is my presentation to the gathering of scientists and faith leaders at the Archdiocese of Boston on February 8, 2018

The Current State of Religious Climate Action in Massachusetts

I am blessed to be here. Thank you, Cardinal O’Malley, for convening us. To you and to everyone here I bring greetings from Bishop Doug Fisher of the Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts, whom I am representing.

I’ve been asked to speak briefly about the current state of religious climate action in Massachusetts, and I’ll start with a word about myself. I was ordained in June 1988, the same month that NASA climate scientist James Hanson testified to the US Senate that scientists were increasingly concerned about the effects of burning fossil fuel and what at that point they were calling “the greenhouse effect.” Concern about climate change was placed on my heart at the very beginning of my ordained ministry, at its root, and in the years since then, I have tried to understand our spiritual and moral responsibility as human beings – as religious leaders – in a time of such great peril.

In 2014 I finally left parish ministry to give the climate crisis my full attention. I now serve as Missioner for Creation Care in the Episcopal Diocese of Western Mass., and in the United Church of Christ across Massachusetts. To me this unusual ecumenical position is a sign of how the climate crisis impels us to come together across faith traditions to organize and mobilize.

Just from looking around, I can say that the interfaith climate justice movement in Mass. is alive and well. With people in this room (and beyond) I’ve preached about climate change and led workshops for clergy on how to preach about climate. With people in this room I’ve led retreats and written pastoral letters and ecumenical statements. With people in this room I’ve pushed for divestment from fossil fuels, lobbied for carbon pricing, marched for climate justice, held prayer vigils, and been arrested for acts of non-violent civil disobedience to keep fossil fuels in the ground.

I am heartened by what I see as an upsurge in awareness and concern here in the Commonwealth among people of faith and good will, and a growing desire to connect the cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor. I am thrilled that The Poor People’s Campaign is taking shape and linking justice of every kind – social, racial, economic and ecological. Meanwhile, I want you to know that a group of people of many faiths is organizing a climate witness that will take place in Boston on Monday in Holy Week, March 26, a few days before Passover. We’re calling it Exodus from Fossil Fuel. We will hold an interfaith ceremony at the State House, appeal to the Governor to stop the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure, and then march in procession to the Back Bay, where a new pipeline project is slated to power luxury high-rises with fracked gas. There we plan to witness to our vision of a beloved community, and to our intention to build a just and livable future for our planet and all its inhabitants. I expect that young people will join us, because I know they are looking for moral leadership on climate. I invite you to join us, too.

The movement is growing, but what we’re missing is an effective, strategic, and well-organized network that mobilizes faith communities from top to bottom, rouses the general public, and becomes an unstoppable force on the political scene. Some of us recently tried and failed to create such a network. Massachusetts Interfaith Coalition for Climate Action (or MAICCA, for short) came into being in 2015, inspired by the release of Laudato Si. It had a good two-year run. MAICCA did many wonderful things, such as making it easy for congregations to become politically engaged, organizing legislative action days at the State House, setting up waves of meetings with local legislators, and taking a leadership role in the huge climate march and rally that was held in Boston in December 2015. But MAICCA ran into trouble – for one thing, we never worked out our organization or a sustainable strategy.

The time is ripe for a new initiative.

I hope for three things:

1) I hope that top leaders of faith communities will make it crystal clear that addressing the climate crisis is central to our moral and spiritual concern. It’s not one of 26 different causes that we care about, but a cause that affects everything we cherish. I hope that top faith leaders will convey to their congregations that if you care about the poor, you care about climate; if you care about immigration and refugees, you care about climate; if you care about public health, you care about climate; if you care about human rights, you care about climate; if you care about loving God and your neighbor, you care about climate. The climate is not an issue for a special interest group. If you like to breathe, if you like to eat, if you’d like to leave your children a world they can live in, you care about climate.

2) I hope that faith communities will get organized within our selves and across traditions so that we become scientifically informed, spiritually grounded, and politically effective, enabling us to speak with one voice about the sacredness of God’s Creation and the moral imperative to protect it.

3) I hope that faith communities will draw from our deep spiritual wisdom as we confront the climate crisis. We know that the massive West Antarctica ice shelves are collapsing and sliding into the sea in a process that some scientists call “unstoppable.” Yet we also know that the love of God is unstoppable. With that love in our hearts and in our midst, who knows what we will be able to accomplish?

Margaret’s monthly “Creation Care Network” e-news is now available on this website. It includes opportunities to learn, pray, act and advocate for the earth. View the archive or subscribe here.