Imagine there is a fire in your house. What do you do? What do you think about? You do whatever you can to try to put out the fire or exit the house. You make a plan about how you can put out the fire, or how you can best exit the house. Your senses are heightened, you are focused like a laser, and you put your entire self into your actions. You enter emergency mode.

These are the opening lines of a fascinating essay that every climate activist and every faith leader should read.

“Leading the Public into Emergency Mode: A New Strategy for the Climate Movement” recognizes that when we face an existential or moral crisis, we can pull back into paralyzed inaction or rush about in panicked, ineffective, chaotic action. But choosing between paralysis and panic is not our only option. Instead, we can enter a state of consciousness in which we become highly focused and purposeful, pour our resources into solving the crisis, and accomplish great feats.

Margaret Klein Salamon, author of the article and the Founding Director of The Climate Mobilization, calls this “emergency mode.” She considers emergency mode a particularly intense form of flow state, which has been described as an “optimal state of consciousness where we feel our best and perform our best.” She cites Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the psychologist who pioneered the study of flow and who described it as: “Being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one… your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.”

When we enter emergency mode, inertia or panic are replaced by focused, productive action toward a few critical goals. Non-essential functions are curtailed. Failure is not an option.

In ordinary times, a country is governed in what Salamon wryly labels “normal political-paralysis mode.” We experience a lack of national leadership, and politics is “adversarial and incremental.” By contrast, when a country is in emergency mode, “bipartisanship and effective leadership are the norm.” People work together because they face a shared and urgent threat.

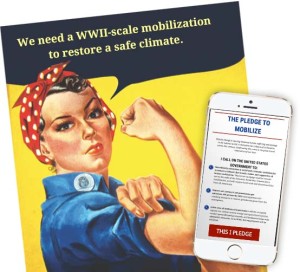

Salamon accurately calls the climate crisis “an unprecedented emergency.” She writes: “Humanity is careening towards the deaths of billions of people, millions of species, and the collapse of organized civilization.” Her article and her organization, The Climate Mobilization, are devoted to developing strategies to mobilize an emergency response. Although I don’t agree with all her policy recommendations, I believe that her basic framing of the challenge is just right.

Most faith communities do not recognize the climate crisis and are not in emergency mode. Yet when faith communities enter this heightened state of awareness about our planetary emergency, we have significant gifts to offer.

(To read the scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change, visit this NASA site and this site from the American Association for the Advancement of Science.)

I. When faith communities understand the climate crisis and enter emergency mode, what roles do we play? We…

• Address helplessness

People who are secretly worried about climate change often don’t take action because they feel helpless and overwhelmed (“The situation is dire. What difference can I possibly make?”). Faith communities address helplessness in multiple ways, both directly and indirectly. For instance, gathering for worship can be understood as turning toward a Higher Power (God, divine Mystery, Creator, Source) in whose presence we are uplifted, and feel our strength renewed. Entrusting ourselves to God can release within us unexpected power “to accomplish abundantly far more than all we can ask or imagine” (Ephesians 3:20).

• Face facts

A person of faith is someone who is committed to the search for truth. A Zen Buddhist might speak of facing reality as it is. A Jew, Muslim, or Christian might speak of relating to an all-seeing, all-knowing God who is truth and who leads us into all truth. At their best, the Abrahamic faiths believe that God has given us the capacity to learn about the created world through the lens of science. Science is one important avenue to discovering what is true. People of faith try to see through self-deception and illusion in their quest to discover what is true and to live their lives in accordance with the truth.

Truth includes both material and spiritual realities. By definition, facts are true until proven otherwise. We do not have any right to our own facts.

Science has established that climate change is real, largely caused by human activities, already inflicting widespread damage, and, unless humanity swiftly changes course, on track to make it difficult or impossible for civilization to continue to exist. We know that 80% of known fossil fuel reserves must stay in the ground, lest we plunge past the point of no return. We know we must make a just and swift transition to a clean energy economy.

Such facts are difficult to face and absorb. But faith communities have the capacity to face facts, tell the truth, and dismiss denial. We trust, and are accountable to, a sacred reality that includes and transcends the material world. From this vantage point, faith communities are uniquely positioned to see through the lies of climate denial. Thanks to our commitment to the truth, we can let go the comfortable fibs and fantasies we may be tempted to tell ourselves (“I don’t need to change; I can continue with business as usual; climate change is someone else’s problem”). We also seek to uncover the confusion, misinformation, and lies about climate change that are deliberately spread by the fossil fuel industry and by the political leaders they fund. Not to do so is to participate in idolatry and to betray our own commitment to bear witness to the truth.

As a Christian, I believe that a religion that directs our gaze to a suffering, dying man on a cross is a religion that can face painful facts. As a Christian, I also believe that perceiving God’s presence in the very midst of suffering and death is a gateway to transformation and new life.

• Provide vision

“Where there is no vision, the people perish” (Proverbs 29:18, KJV).

Climate science has done its job, giving us essential facts about the potentially catastrophic consequences of continuing to burn fossil fuels. But facts alone are not sufficient to persuade people to take meaningful, concerted action. For that, we need vision – a shared goal, purpose, and values. This is what faith communities can do: lift up a vision of people living in just and loving relationships with each other and with the whole Creation, a vision energized by a deep desire for God’s love to be fully manifest in the world. Faith communities have a vital role to play in inspiring action to safeguard the world that God entrusted to our care.

As Antoine de Saint Exupery observed, “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” Simon Sinek makes the same point in his terrific TED talk, “How Great Leaders Inspire Action,” when he says, “Martin Luther King, Jr. gave the ‘I have a dream’ speech, not the ‘I have a plan’ speech.”

• Offer hope

Human beings hope for so much: we want a good future for our kids; we want a livable world; we want the web of life to remain intact. The climate crisis challenges these cherished hopes. It renders uncertain the future of the whole human enterprise.

Faith communities offer a context in which to explore and take hold of the kind of hope that does not depend on outward circumstances but that emerges from a deep and irrepressible place in the human spirit. Animated by a radical, God-given hope, people of faith throw themselves into healing the Earth and its communities, human and other than human. Active hope – actively embodying ones deepest values and being ready at every moment to welcome and build the longed-for future – is a path to joy.

• Renew love

Climate change is a “threat multiplier” that exacerbates existing problems, such as poverty, hunger, terrorism, refugees on the move, and the spread of infectious diseases. Racism, militarism, and xenophobia – the fear of what is perceived to be foreign or strange – are likely to increase as the planet warms and as various groups battle over depleted resources, such as arable land and clean drinking water. Religious groups, like every other group, can be hijacked by fear and become sources of discord and violence.

Yet the deep message of all the world’s religions is that we are interconnected with each other and with the Earth on which all life depends. Faith communities can help to restore our capacity to love God and our neighbor. The climate crisis is already bringing together leaders and members of many faiths in a unified call to protect Earth and all its inhabitants, human and other than human. Pope Francis’ landmark encyclical on climate justice, Laudato Si’, generated an ardent and enthusiastic response from diverse faith communities around the world.

In a sermon, a D’var Torah, or a dharma talk, in prayer circles, worship services, and meditation groups, in pastoral care, outreach, and advocacy, faith communities can renew our intention and deepen our capacity to act in loving ways, to respect the dignity of every human being, and to cherish the sacredness of the natural world.

Faith communities speak to the heart of what it means to be human. When people are going mad with hatred and fear, only love can restore us to sanity.

• Give moral guidance

The climate crisis raises existential questions about the meaning, purpose, and value of human life. What is our moral responsibility to future generations? What does it mean to be human, if human beings are destroying life as it has evolved on this planet? How do we address the anger, self-hatred and guilt that can arise with this awareness? How can we live a meaningful life when so much death surrounds us? How determined are we to radically amend our personal patterns of consumption and waste? What does living a “good” life look like today, given everything we know about the consequences of over-consumption, inequitable distribution of resources, and being part of (and probably benefiting from) an extractive economy that depends on fossil fuels and unlimited growth?

Faith communities provide a context for wrestling with these questions, for seeking moral grounding, and for being reminded of such old-fashioned values as compassion, generosity, self-control, selfless service, simple living, sacrifice, sharing, justice, forgiveness, and non-violent engagement in societal transformation.

Maybe we should think of the climate crisis as our doorway to enlightenment. The climate crisis challenges us, individually and collectively, to expand our consciousness and to live from our highest moral values. As Jayce Hafner points out in an article published in Sojourners, “I’m Ready to Evangelize…About Climate,” “The act of confronting climate change calls us to be better Christians in nearly every aspect of our lives.”

I expect that this is true not only for Christians, but for people of every faith.

• Encourage reconciliation and seek consensus

The coal miner who just lost his job… the CEO of a fossil fuel company who is making plans to drill for more oil… the woman whose home was destroyed by Hurricane Sandy… the farmer watching in despair as his crops wither from a massive drought… the construction worker laying down pipeline for fracked gas… the activist arrested for stopping construction of that pipeline… these are just some of the people who probably have wildly divergent views about the climate crisis and who may feel harmed by and angry with each other.

The climate crisis includes both victims and offenders. To some degree (though to quite different degrees) all of us bear some responsibility for the crisis. At the same time, all of us have a part to play in healing the damage and contributing to a better future. As we work to transition to a clean energy economy whose benefits are available to all communities, we need all hands on deck. Entering emergency mode requires that people work together toward a shared and deeply desired goal, and we need the participation and input of every sector of society as we try to protect our common home. As an African proverb puts it, “Two men in a burning house must not stop to argue.”

Faith communities can provide settings for difficult conversations, active listening, and “truth and reconciliation” groups modeled on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that was formed in South Africa in the 1990’s after apartheid was abolished. By expressing compassion while also holding groups and individuals morally accountable, faith communities can create possibilities for reconciliation and collaboration that would otherwise never exist. What’s more, because of their historic commitment to the oppressed, marginalized, and poor, faith communities can give voice to the needs of people and all creatures who are generally ignored or exploited by the people in power.

• Allow emotional response

The climate crisis can make us go numb. Why think about the enormous stretches of coral reefs in Australia that just died in less than two months? What can we possibly feel in response to the acidifying ocean, the children choking from asthma in our inner cities, the rising seas, the ever-increasing droughts and floods, and the cascade of species going extinct?

The climate crisis can make us go numb. Why think about the enormous stretches of coral reefs in Australia that just died in less than two months? What can we possibly feel in response to the acidifying ocean, the children choking from asthma in our inner cities, the rising seas, the ever-increasing droughts and floods, and the cascade of species going extinct?

It is hard enough to face our own mortality or to mourn a loved one’s death. How do we begin to explore our fear and grief in response to the ecocide going on around us – much less express it? How do we move beyond despair?

Faith communities can give us practices, teachings, and rituals that allow us to feel, express, accept, and integrate the painful emotions evoked by climate change.

To ignite and sustain an emergency response, society needs to overcome what Salamon calls our “affect phobia,” our tendency to repress our feelings and to react to climate change only in terms of intellectual analysis and facts (How many heat records were broken last month? How many parts per million of CO2 are in the atmosphere now?). With the support of communities of faith, we can protect our human capacity to feel our emotional responses to the crisis without being overwhelmed by grief. Our emotions can also become a source of energy for constructive action to address the emergency.

(For a comprehensive overview of the psychological impacts of climate change, take a look at “Beyond Droughts and Storms,” prepared by ecoAmerica and the American Psychological Association.)

• Offer pastoral care

Faith communities can provide practical and spiritual assistance during climate-related disasters such as hurricanes, floods, and wildfires. Congregations can make “disaster preparedness plans,” prepare a response in collaboration with local agencies, and develop networks of communication. One leader involved in this kind of preparation comments that congregations can be “sanctuaries of hope in times of disasters.”

In some areas of the world, the need is already urgent: at least five Pacific islands have disappeared under rising seas since the Paris climate talks last December. The Anglican Church in that area is developing “a clear resilience strategy.”

Faith communities can also provide comfort and solace day by day. We can develop networks of pastoral care and spiritual outreach to address the rising rates of depression, anxiety, and other psychological challenges that are associated with climate change, being mindful that low-income communities may be particularly vulnerable to climate-related stressors.

• Heighten reverence for nature

In a society that treats the natural world as an object to master, dominate, and exploit, faith communities can call us back to the sacredness of the Earth. Faith communities can support the efforts of land trusts to preserve farms, woods, wetlands, and open space (to locate your local land trust, visit Land Trust Alliance); can partner with organizations to bring inner-city children into natural settings; and can sponsor retreats and hikes that explore the wonders of Creation. Faith communities can learn, and help others to learn, what a stone or cloud or bird can teach (see, for instance, “Opening the Book of Nature,” developed by National Religious Coalition on Creation Care). They can help people from different religious background to become environmental leaders (see, for instance, the programs of GreenFaith and of The Center for Religion and the Environment at Sewanee). Some communities of faith gather for spiritual practice outside. For instance, Church of the Woods in Canterbury, NH, founded by the Rev. Steve Blackmer, is a new kind of “church”: “a place where the earth itself, rather than a building, is the bearer of sacredness.”

• Inspire bold action

Faith communities have a long history of leading movements for social and environmental justice, from child labor to women’s rights, peace, the abolition of slavery, and the civil rights movement. Faith communities tap into our capacity to dedicate ourselves to a cause that is greater than our personal comfort and self-interest. Faith in God (however we name that Higher Power) can inspire people to take bold actions that require courage, compassion, and creativity.

Faith communities can model best practices for “going green,” such as to get an energy audit, increase energy conservation and efficiency, look into installing solar panels, put in bike racks, replace lawns with community gardens, and so on. But taking care of our immediate buildings and community is just a start. An adequate response to the scope and speed of the climate crisis requires collective action and political engagement.

Faith communities can model best practices for “going green,” such as to get an energy audit, increase energy conservation and efficiency, look into installing solar panels, put in bike racks, replace lawns with community gardens, and so on. But taking care of our immediate buildings and community is just a start. An adequate response to the scope and speed of the climate crisis requires collective action and political engagement.

Because of the current gridlock in Congress, it can be tempting either to quit participating in democracy entirely or to stay engaged but demonize our opponents. A recent blog post by my bishop, the Rt. Rev. Doug Fisher, persuasively contends that because Christianity is a “world-engaging faith,” people who follow Jesus must stay politically engaged and also encourage civil, non-partisan, political discourse that serves the common good.

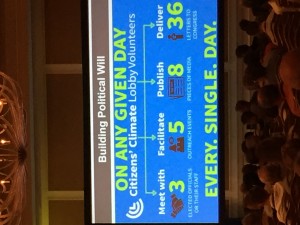

The climate emergency is propelling people of different faiths to organize and to lobby for strong legislative action. See, for instance, the national work of Citizens Climate Lobby to put a fair and rising price on carbon, whose volunteers include clergy and members of congregations, and the national work of Interfaith Power & Light, which has an affiliate here in Massachusetts. MA Interfaith Coalition for Climate Action, launched only months ago (full disclosure: I’m on the Leadership Team), is pressing for timely, high-impact changes in laws and systems in our Commonwealth.

In the footsteps of trailblazers such as Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., hundreds, maybe thousands, of people, including countless people of faith, have been arrested in recent years as non-violent resistance to fossil fuels continues to grow. With fifteen other religious leaders, I was arrested on May 25 at a prayerful protest against construction of Spectra’s West Roxbury Lateral pipeline in Boston. On June 29 twelve faith leaders – Buddhist, Jewish, Protestant, and Unitarian Universalist – were among 23 people arrested in another protest of the same pipeline. In solidarity with the hundreds of people who recently died from deadly heat waves in Pakistan and India and were buried in mass graves, the clergy led a climate ‘mass graves’ funeral, featuring eulogies, prayers, and mourning, with some of the resisters lying down in the grave/trench for nearly two hours.

By inspiring significant action, such as divesting from fossil fuels and engaging in civil disobedience, faith communities can challenge the deathly status quo of “business as usual” and rouse society out of its apathy and inaction.

For religious leaders who want to network with colleagues to engage in visionary and prayerful civil disobedience, sign up at ClergyClimateAction.org.

To join an epic march, July 14-18, against new gas pipelines that will go all the way to the Massachusetts State House, visit People Over Pipelines.

Boston Globe article: “Al Gore’s Daughter Arrested in Boston Pipeline Protest”

Tim DeChristopher’s powerful reflection in word and video: “Grief and Resistance: The Mass Grave Pipeline Action”

Democracy Now! interview: “Tim DeChristopher Arrested Again in the ‘Age of Anticipatory Mass Graves’ for Climate Victims”

Democracy Now! interview: “Vice President’s Daughter Karenna Gore Arrested in the Trenches of a Climate Protest”

Press release: Symbolic Climate Mass Grave Funeral to #StopSpectra

II. When faith communities understand the climate crisis and enter emergency mode, what tools do we offer?

• Storytelling

The myths, tales, parables and stories of religious traditions give us powerful ways to re-imagine our selves and our situation, and to absorb deep (not necessarily literal) truths. Stories speak not just to our rational mind but also to our affections, will, and imagination. From the Judaeo-Christian tradition, stories of Moses confronting Pharaoh and of Jesus healing, teaching, suffering, dying, and rising again – all these and more can be brought to bear to address the climate crisis and to give us courage, guidance, and motivation to act. Recently I learned that activists fighting to stop construction of a trash-burning incinerator in a low-income neighborhood of Baltimore are using the story of Naboth’s vineyard (1 Kings 21:1-21a) to illuminate their own experience of social and environmental injustice and to inspire their own acts of resistance.

• Prayer and silence

Every faith tradition offers practices that teach us how to move out our habitual narrow orbit of self-involvement and to connect with a larger, sacred reality. The climate crisis invites people who until now have felt immune from any desire to pray, to explore practices of prayer and meditation.

Expressive forms of prayer empower us to move beyond denial and numbness and to acknowledge the full range of our feelings. My article, “Feeling and pain and prayer,” originally published in Review for Religious, presents four ways that Christians can pray with difficult feelings. The article also describes how expressive prayer can change us over time, deepening our sense of intimacy with God, our experience of a peace that passes understanding, and our capacity to move from helplessness and hopelessness to effective action.

Contemplative forms of prayer (such as Centering Prayer and mindfulness meditation) strengthen our capacity to sit in silence with the unknown, to accept impasse, and to keep listening and trusting even in the darkness. Practices that lead the mind into silent awareness offer more than a respite from thinking about the climate crisis. They can open us to an intuitive, non-verbal experience of communion, even union, with others, with the natural world, and with ultimate reality. Experiencing our unshakable union with a love that is stronger than death is the great gift of contemplative prayer. Rooted in that fierce and openhearted love, we are guided to actions commensurate with the emergency we’re in.

• Rituals

Faith traditions offer a range of ceremonies and rituals that seek to awaken our awareness and revive our relationship with a sacred presence or power beyond the limited world of “I, me, and mine.” In a time of climate crisis, people need rituals that address our fear of death and give us courage to trust in a life greater than death. We need rituals that ask us to name our guilt and regrets, that grant us forgiveness, and that give us strength to set a new course. We need rituals that remind us of our essential connection with each other, with the rest of the created world, and with the unseen Source of all that is. We need rituals that remind us of how loved we are, how precious the world is, and what a privilege it is to be born in a time when our choices and actions make such a difference.

Faith communities have a heritage of holy days, festivals, days of atonement, and liturgical seasons that gain fresh meaning in light of the climate crisis.

• Sermons

It takes courage to preach about climate change. If you’re a faith leader who speaks or preaches frequently about the climate emergency, then yours is a rare and much-needed voice. If you’re a member of a faith community whose leaders speak rarely, weakly, or never about climate justice, then please give them steady encouragement to say what needs to be said.

As my climate activist friend and colleague, Rev. Dr. Jim Antal (Conference Minister and President, Massachusetts Conference, United Church of Christ) often says, if clergy don’t preach about climate change every few weeks, then in ten or fifteen years every sermon will be about grief.

My own ongoing efforts to preach a Christian perspective on climate are here. Last year’s “A New Awakening,” an ecumenical initiative to promote climate preaching across New England, has a Webpage of preaching resources. I just received a copy of Creation-Crisis Preaching, by Leah D. Schade, which looks like indispensable reading.

• Public liturgies and outdoor prayer vigils

Over the years I’ve led or participated in many outdoor interfaith public liturgies about climate change. In the wake of environmental disasters such as the Gulf of Mexico oil spill or Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, or on the eve of significant environmental events, such as Pope Francis’ visit to Washington, D.C. or the U.N. climate talks in Paris, people of all faiths often feel a need to gather so that we can express our grief, name our hopes, and touch our deep longing for healing and reconciliation. Faith communities can lead the way in providing public contexts for renewing our spirits, both indoors and outside.

III. What does this add up to?

Faith communities can become agents of transformation.

Humanity stands at a crossroads. As individuals and as a species we face a decision of ultimate importance both to our souls and to the future of life. “I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses. Choose life so that you and your descendants may live” (Deuteronomy 30:19).

This is not a fire drill. This is an actual emergency. Martin Luther King, Jr. got it right: we face “the fierce urgency of now.” “See, now is the acceptable time; see, now is the day of salvation!” (2 Corinthians 6:2).

Armed with this knowledge, faith communities can enter emergency mode. Speaking as a Christian, I envision a church in which every aspect of its life, from its preaching and worship services to its adult education and Sunday School, from its prayers to its public advocacy, grasps the urgency of protecting life as it has evolved on this planet. That is the kind of Church that the world needs today.

I am thankful for all people who are willing to face squarely the most challenging, even devastating facts; who reach into their reserves of courage, faith, and hope; and who step out to bear witness in very tangible ways – even in the face of suffering and death – to the ongoing presence and power of a love that abides within us and that sustains the whole creation.

“The huge West Antarctic ice sheet is starting to collapse and slide into the sea in a way that scientists call ‘unstoppable.’ …If ever there were a time to bear witness to our faith that life and not death will have the last word, now would be the time. If ever there were a time to take hold of the vision of a Beloved Community in which human beings live in right relationship with each other and with all our fellow creatures, now would be the time. The collapse of the ice sheet in Antarctica may be ‘unstoppable,’ but so is the love that calls us to stand up for life.”

— Excerpt of my sermon, “Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Climate Movement,” January 18, 2015

You can download an article adapted from this blog post by clicking here: How can faith communities address the climate crisis?

NOTE: I was prompted to write this essay after serving on a panel of faith leaders at the 2016 conference of Citizens Climate Lobby in Washington, DC. The panel’s moderator, Peterson Toscano, asked two questions: What role(s) do you see faith communities take on in times of crisis? What tools does your faith tradition offer that can be used to address climate change? The four panelists included Dr. Steven Colecchi (Director of the Office of International Justice and Peace, U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops), Rachel Lamb (National Organizer and Spokesperson, Young Evangelicals for Climate Action), Joelle Novey (Director, Greater Washington Interfaith Power and Light), and me. The hour was over well before we’d finished exploring the topic. This essay is a bid to extend the conversation.

“1.5 to stay alive” – that is the cry of every God-inspired prophet who stands like Elijah beside the vulnerable Naboths of this world.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with the low-income community of Baltimore that is fighting for the right to clean air.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with Pacific Islanders forced to leave their homeland because rising waves are washing away their buildings and contaminating their water supply.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with indigenous peoples in the Arctic whose cultures are disintegrating as the ice melts.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with frightened pregnant women in the global South and the Southern U.S. who know that the Zika virus, which spreads in a warm, humid climate, could irreparably harm their unborn child.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with every person and every community that wants to live in a just and peaceful world with recognizable seasons and moderate, predictable rains, in a world with enough clean, fresh water for all and an ocean teeming with life.

And we say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand against the political and corporate powers that view the Earth as nothing more than a source of profit and who exploit the Earth and other people as if it’s every man for himself and the Devil take the hindmost.

Thanks to Bob Parati, we have a sign that proclaims, “1.5 to stay alive.” After the service, I invite anyone who wishes, to join me outside so that we can take a group photo.

I invite you to do some other things, too. If you haven’t done so already, I invite you to join

“1.5 to stay alive” – that is the cry of every God-inspired prophet who stands like Elijah beside the vulnerable Naboths of this world.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with the low-income community of Baltimore that is fighting for the right to clean air.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with Pacific Islanders forced to leave their homeland because rising waves are washing away their buildings and contaminating their water supply.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with indigenous peoples in the Arctic whose cultures are disintegrating as the ice melts.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with frightened pregnant women in the global South and the Southern U.S. who know that the Zika virus, which spreads in a warm, humid climate, could irreparably harm their unborn child.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with every person and every community that wants to live in a just and peaceful world with recognizable seasons and moderate, predictable rains, in a world with enough clean, fresh water for all and an ocean teeming with life.

And we say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand against the political and corporate powers that view the Earth as nothing more than a source of profit and who exploit the Earth and other people as if it’s every man for himself and the Devil take the hindmost.

Thanks to Bob Parati, we have a sign that proclaims, “1.5 to stay alive.” After the service, I invite anyone who wishes, to join me outside so that we can take a group photo.

I invite you to do some other things, too. If you haven’t done so already, I invite you to join

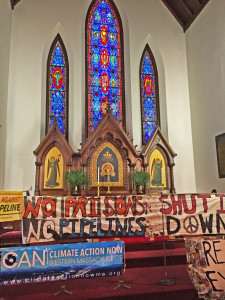

As a Christian climate activist, I found it stirring to realize that the rally was taking place on the eve of Palm Sunday, the day that Christians around the world step into Holy Week. Here were the stately altar and lectern arrayed in cloths of traditional red colors for tomorrow’s service, yet here, too, were banners draped across altar, pulpit and lectern, crying out in large letters: “No Prisons, No Pipeline. Shut It Down,” “Respect Existence, Expect Resistance,” and “Love Will Win.”

As a Christian climate activist, I found it stirring to realize that the rally was taking place on the eve of Palm Sunday, the day that Christians around the world step into Holy Week. Here were the stately altar and lectern arrayed in cloths of traditional red colors for tomorrow’s service, yet here, too, were banners draped across altar, pulpit and lectern, crying out in large letters: “No Prisons, No Pipeline. Shut It Down,” “Respect Existence, Expect Resistance,” and “Love Will Win.”