This article by Margaret Bullitt-Jonas first appeared in the Volume 44 (2022) issue of Buddhist-Christian Studies, published by the University of Hawai‘i Press, pp. 69-83. You can download a .pdf copy of the article here.

Facing climate crisis and ecological collapse requires courage and tenderness. Courage, because it takes courage to see clearly what human beings are doing to our precious planet. It takes courage to hold a steady gaze and to witness the melting glaciers and bleaching coral reefs, the withered fields and bone-dry reservoirs, the flash floods and massive downpours, the record waves of heat. It takes courage not to look away but to hold a steady gaze as climate change makes sea levels rise and islands disappear, as oceans grow acidic and full of plastic, and as vast populations of our fellow creatures disappear.

Tenderness brings moments – maybe this is one of them – when we allow ourselves to feel our emotional response to what we have lost and are losing as climate change accelerates and as governments and financial institutions in thrall to the fossil fuel industry fail to take decisive action to address the crisis.

I am neither an academic nor a scholar. This paper will not report on research nor analyze sacred texts. Instead, it will reflect on some of the spiritual practices and perspectives that guide my work as an Episcopal priest dedicated to mobilizing a Spirit-filled, faithful response to climate crisis.

At this hinge point of history, practitioners of every faith tradition must ask ourselves: What are the gifts that our tradition can bring to the table as the human community – and the whole Earth community – experience the rapid unraveling of the web of life? What are we called to do? In what spiritual practices shall we root ourselves so that we can rise up with determination, courage, and compassion to take effective action? I’m very interested in what helps us to move beyond inertia, panic, and despair and to give ourselves wholeheartedly to the movement to address climate change – so interested, in fact, that a friend and I asked colleagues in the faith-and-environment movement to write about their sources of spiritual strength. How do they maintain courage, empathy, and determination? Our anthology of essays is entitled Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis.1

I speak as a Christian who is deeply indebted to the wisdom of Buddhism. My late mother, Sarah Doering, was a devoted practitioner and teacher of vipassanā (insight) meditation and for seventeen years attended the three-month silent retreats at Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts. Because of her teaching, counsel, philanthropy, and spiritual support, she is credited by IMS with playing a vital role in helping Buddhism to flourish in the West.2 My husband, Robert A. Jonas, has also had a long-standing interest in Buddhist practice. Years ago, he founded a small, contemplative Christian center for meditation and prayer, The Empty Bell,3 which has sponsored many Buddhist-Christian dialogues; he met His Holiness the Dalai Lama three times at Buddhist-Christian retreats in various parts of the world; and he is an active member of this society. I am also deeply grateful for Joanna Macy, with whom I’ve studied and whose teachings have helped me and countless others to reflect on our human predicament and find a path to healing. I bow to these important people in my life, and to everyone who is nourished by Buddhist teaching and practice.

My own experience of Buddhist meditation opened me to a deeper understanding of Christianity, the faith tradition in which I was born and raised, and which I fled after high school. Buddhist meditation not only facilitated my return to the church – it also gave me my first glimpse of the vocation that would become my life’s work. I began learning and practicing vipassanā meditation in the early 1980’s, when I was in my 30’s. I was just beginning to recover from a food addiction that had plagued me since adolescence, and just beginning to explore what it meant to pay attention to my inner and outer experience. I particularly remember a ten-day silent retreat that I attended at IMS. As the teacher instructed, I followed the drill: You sit. You walk. You sit. You walk. That’s it. You do nothing but bring awareness to the present moment.

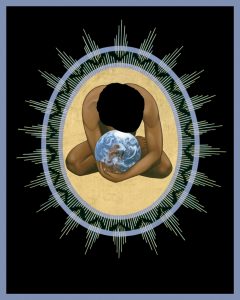

One day I left the retreat house for a walk in the woods. I paid attention to sensations as they came, the feel of my foot on the ground, the sound of birds, the sight of birches, hemlock, and pine. I was nothing but eyes and ears, the weight of each foot, the breath in my nostrils. At one point I stopped walking, overwhelmed by the sense that the whole world was inside me. I was carrying the round blue planet inside my chest. My heart held the world. I cradled it tenderly, weeping with joy.

I did not know it then, but that vision of carrying the world in my heart would become one of the core images to which I would return in prayer in the decades ahead, a place of consolation that renewed my strength for climate activism. Years later, someone gave me a contemporary icon of Christ bending over the world, his arms embracing the planet.4 I caught my breath in recognition. Yes, that’s right. That’s just how it is.

Learning through vipassanā meditation to steady my mind and make contact with my actual experience opened me to a flow of love that I didn’t understand and couldn’t have predicted. Time and again, as I sat in meditation, welcoming everything into awareness, clinging to nothing and pushing nothing away, an unexpected tenderness would rise up from within and gather me up like a child. Baffled, I went back to Sunday services in the church I had fled long ago, sat in the shadowy back pews, and marveled at the possibility that the preacher who claimed that God is love was not just a blithering idiot but might actually be on to something. My recovery from addiction through the 12-Step program depended on daily surrender to a so-called Higher Power that was vaster and wiser than my fragmented, isolated ego-self. I began to hope – and then suspect – that this “higher” power might be the power of divine love.

I finished what I was doing and headed to seminary, eager to know more about the God who had saved my life. I began to study and practice Christian contemplative prayer and learned about the mystics who encountered God in silence. I was ordained in the Episcopal Church in June 1988, the same month that NASA climate scientist James Hanson warned Congress that the extraction and burning of fossil fuels was disrupting the global atmosphere. It was the first time I’d heard about what was then called the “greenhouse effect.” Stunned, I touched the newspaper with my fingers and breathed, feeling again the love for the world which had been so mysteriously revealed at that Buddhist retreat center. A question emerged that became the riddle of my life, a question that to this day fuels my vocation as a faith-based climate activist: If God can empower a crazy addict like me to make peace with her body, is it not possible that God can empower us crazed, addicted human beings to make peace with each other and the body of Earth?

For 25 years I served in parish ministry; on the side, I led retreats, taught seminary classes on prayer, and was a climate activist. Finally, in 2013, I went to my bishop in the Diocese of Western Massachusetts and confessed that I needed to leave parish ministry: anxiety about the climate crisis was keeping me awake at night. I asked if he could create a job in the diocese to let me focus full-time on mobilizing Christians to protect the living world that God entrusted to our care. God bless him, Bishop Doug Fisher said yes, if funds for such a job could be found. Lo and behold, just then a parishioner came forward who had sold his shares of stock in oil pipelines and wanted to donate the funds to the diocese to address climate change. That became the seed money for my job – which quickly went ecumenical. I now serve both of the Episcopal dioceses in Massachusetts, as well as the United Church of Christ in Southern New England, and I maintain a website, RevivingCreation.org.

Christianity is my root tradition and the one I know best, but obviously there are many ways to construct Christianity. Some versions of Christianity have inflicted, and continue to inflict, enormous harm on human beings, the land, and the other creatures with whom we share this planet. Christianity has been used to justify slavery and white supremacy, patriarchy, homophobia, colonialism, and a definition of “dominion” that permits and even encourages a wholesale assault on Mother Earth. Christianity has been hijacked to bless the Doctrine of Discovery and the unjust claims of Manifest Destiny. Who knows how many Black, brown, and indigenous peoples – as well as people of different faiths – have been enslaved, dispossessed, or killed in the name of Jesus? What’s more, growing up in the 1950’s, I heard nothing in my church about God’s love for or participation in the natural world. The God I grew up with had no body. God was pure spirit and, as far as I could tell, essentially disconnected from the material world. Among the myriad life-forms that God created, God apparently cared about only one, Homo sapiens – all the other creatures and elements of the natural world were, at best, scenic backdrop and bit players in the only drama that mattered to God: the human drama. Even now, as Rev. Cameron Trimble points out, the pews of conservative Christian churches are filled with people who believe – mistakenly – “that nature is available for our endless consumption, that short-term profit outweighs plenary survival, access to resources should be owned by a few rather than available to all, and in the end, technology will save us.”5

A socially just, ecologically wise, and spiritually mature Christianity must begin with an act of repentance and humility. In the face of climate emergency and species extinction, every religious tradition, beginning with Christianity, must reckon with the aspects of its heritage that no longer serve life and must critique, discard, or transform the practices and perspectives – however ancient and long-standing – that do not meet the challenge of this planetary crisis. At the same time, every religious tradition, including Christianity, must sift through its teachings, practices, and rituals to locate the gold, the elements of deep ecological wisdom that the human community so desperately needs. Every religious tradition, including Christianity, must also ask itself: How does this unprecedented moment in human history challenge us to evolve so that we truly serve the common good? Now is the time to ask and address these questions, for scientists tell us that we don’t have much time to avert a catastrophic level of suffering and to preserve a habitable world for our children, our children’s children, and all the other creatures with whom we share this planet.

The world around us is dying. How can we – teachers, students, and practitioners of spiritual wisdom in a variety of contexts – be of use?

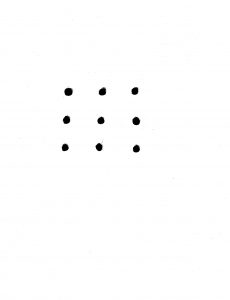

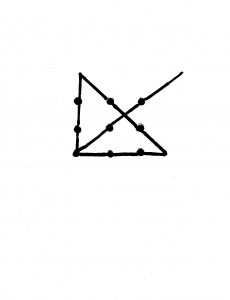

Here’s an image to consider. There is a puzzle6 that consists of nine dots on a page, lined up in rows of three. The goal is to connect the dots by making four straight lines without once lifting your pencil from the page or retracing the same line. The only way to connect all nine dots with just four straight lines is to go outside the borders of the box. Solving this puzzle is an example of “thinking outside the box,” of moving beyond a given paradigm in order to perceive or accomplish something that otherwise couldn’t be perceived or accomplished.

That’s what religious and spiritual traditions are meant to do: to help confused, isolated, and fearful human beings to think, feel, and understand outside the box of our little ego-selves so that we can experience our connections to each other and to a sacred Reality greater than “I,” “me,” and “mine.” Imagine that we live in a world in which everything feels fragmented, divided, and falling apart, a world in which a beloved landscape can go up in flames, a flash flood can drown people in a subway, a mass shooting can take place in your local grocery store, and starving birds can fall dead from the sky. Imagine a world in which people feel helpless, frightened, and alone, more tethered to their cell phones and social media than to each other, more ready to arm themselves and stock food in their basement than to reach out to help a neighbor, and perfectly willing to douse their lawns with herbicides and to eat cheap beef from a factory farm because the fate of other creatures is of no concern. Imagine isolated dots, trapped in an increasingly hot, harsh, and violent world that could well tumble into social and ecological collapse.

Imagine now that we find four lines of thought or four arrows of prayerful intention that disclose an underlying wholeness and unity. What if those isolated dots – what if all of us – discovered that we were held together in a sacred reality, that we were embraced by a love that created all things, connects all things, and sustains all things? On the surface, in the realm of our senses, we might notice only differences, what divides us from each other, but in the deep center of reality we would sense common ground that holds everything together, drawing us into community with each other and drawing us into communion with the sacred Mystery that some of us call “God.” Now we would be living outside the box. And from this place we could begin to heal ourselves and an ailing world.

Here are four lines of thought, four arrows of prayerful intention that help me step out of the box and into a larger, wilder place where I can envision social and ecological healing and find strength to take action.

Here are four lines of thought, four arrows of prayerful intention that help me step out of the box and into a larger, wilder place where I can envision social and ecological healing and find strength to take action.

1. First arrow: We cultivate an interior relationship of love. In ways that resonate with Buddhism, one of the great promises of Christianity is that in silence and solitude, through practices of contemplative meditation, we can learn to listen to the inner voice of love that is always sounding in our hearts. Christians imagine Jesus in many different ways, but one of the most compelling is expressed by the 18th-century Methodist, Charles Wesley: “Jesus, thou art all compassion, pure, unbounded love thou art.”7 Like filings to a magnet, we may be drawn to that love, yearning to receive, experience, and embody it more fully every day. We may be drawn to imageless forms of prayer, such as Centering Prayer or the Jesus Prayer, which use a sacred word or two to guide our longing to encounter the Divine, the ultimate mystery beyond words, thoughts, or feelings. We may pay attention to each breath, consciously breathing in the love of God and breathing it out into the world. One of the earliest Christians, a Desert Father named Anthony, advised, “Always breathe Christ.”8 Or we may simply wish to rest in God’s loving gaze and to pray the simplest of prayers: I gaze at God, and God gazes at me. That is how the 17th-century Carmelite monk Brother Lawrence describes what he calls the practice of the presence of God. He writes, “I… concentrate on being always in [God’s] holy presence; I keep myself in [God’s] presence by simple attentiveness and a loving gaze upon God… to whom I often feel myself united with greater happiness and satisfaction than that of an infant nursing at his mother’s breast; also for the inexpressible sweetness which I taste and experience there, if I dared use this term, I would willingly call this state ‘the breasts of God.”9

Similarly, in words that recall the practice of mindfulness meditation, the 18th-century French Jesuit, Pierre de Caussade, speaks of what he calls “the sacrament of the present moment.” In my tradition, sacraments are special ceremonies that convey the grace and presence of God – outward forms that convey inward spiritual realities.10 De Caussade argues that every moment should be received with the reverence with which we receive a sacrament. Since every moment is filled with God’s infinite holiness, every moment should be honored.11

What I’m trying to describe is how we can move through our days with a deep inner stability, a confidence that moment to moment we are resting within a relationship of love. The accent is relational – we turn toward a holy You (capital Y) whose presence is with us wherever we go. Human beings thrive in the context of loving relationships, and whether sitting or standing, walking or waiting, we can tune our awareness to an intimate Someone (capital S) whom we may name and experience in different ways but in whose usually subtle but sometimes vivid presence we feel seen, known, and loved.

Why is this relevant to facing ecological collapse and climate change? Because when people are in the grip of collective trauma, they need practices that steady the mind, calm the nervous system, and restore a sense of inner safety and accompaniment. Because drawing from a sacred, inner wellspring is a source of solace and strength for anyone facing a difficult present and the likelihood of an even more difficult future.

What’s more, as climate change intensifies, we are increasingly likely to hear messages such as “The world would be better off without human beings” or “Human beings are a cancer on the planet.” I understand the bitterness and grief in statements like these, and I recognize that, in some ways, these messages are accurate: economic systems that depend on dirty fossil fuels, endless expansion, and relentless extraction of natural resources are indeed taking down life on Earth. But the only way forward is not to feed the voice of self-hatred, but instead to listen to the voice of love. Only love can empower us to imagine new possibilities, relinquish a killing status quo, and set out on a different path. When people are going mad with hatred and fear, only love can restore us to sanity.

2. Second arrow: We awaken to the love that is everywhere. Falling in love with Jesus or with the God we find within does not lock us into a private world of our own. On the contrary, when we follow Jesus, we follow him straight into the wide-open heart of the Father/Mother of our souls, the Creator who loves every inch of the created world and who, according to the mythic story, at the beginning of time pronounced everything “very good” (Genesis 1:31). Participating in the flow of divine love means that our tightly gripped sense of self must dissolve and expand. Our little ego didn’t invent this love; we didn’t create it, we can’t control it, and it’s a lot bigger than we are – or to be more accurate, bigger than who we think we are. In truth, it is the essence of who we are, what Thomas Merton would call our True Self. Even if we’d like to hoard God’s love for ourselves or our own little tribe, when we are drawn into the heart of God, we discover that everyone else is there, too. As Fr. Henri Nouwen would say,12 when I know deeply that I am the beloved – when God breaks through my layers of resistance and self-doubt and reveals that I am cherished to the core – then I discover that everyone is the beloved. Everyone is cherished by God. No one is left out.

This is a radical, out-of-the-box message in a dog-eat-dog world of frenzied competition, where people elbow each other in a zero-sum game for status, possessions, and power, and where nations and corporations too often run roughshod over the needs of the land and the needs of the poor. By contrast, a love that encompasses all people and all sentient beings calls us to live in harmony with each other and the rest of creation. Such love asserts moral values quite different from those of late-stage capitalism. I will name two: intersectional justice, and reverence for the natural world.

Intersectional justice understands that everything is connected. For instance, climate change is linked to economic and racial injustice. Although climate change is largely caused by wealthy nations and communities, its impacts are felt first and most painfully by low-income and minority communities – the very communities least likely to have contributed to the crisis, least able to adapt to it, and least likely to have a voice at the table where policy decisions are made. We risk participating in “climate apartheid,” where the rich pay to escape the increasing heat and hunger caused by the climate crisis and the rest of the world suffers.13 We also risk “climate gentrification,” where wealthy people seeking refuge from the effects of climate change move into once “undesirable” neighborhoods, forcing out low-income and minority residents.14

Climate justice is so closely linked to racial justice that some people contend that we wouldn’t have climate change without white supremacy. Where would we put our urban oilfields, our dumping grounds and trash, our biomass plants, our toxic incinerators and other polluting industries, if we weren’t willing to sacrifice Black, Brown, and indigenous communities? To quote the Sierra Club’s Hop Hopkins, “You can’t have climate change without sacrifice zones, and you can’t have sacrifice zones without disposable people, and you can’t have disposable people without racism.”15

Climate change is not one of 26 different causes that we care about – it is a cause that affects everything we cherish. The Pentagon has long called climate change a “threat multiplier,” which means that it amplifies existing problems, from national security and public health to poverty, hunger, and immigration. That is why it is so important to build an intersectional movement that pulls people out of their isolated siloes of concern and pushes for comprehensive solutions. Environmentalism used to be a movement mainly of white people defending polar bears and wilderness areas, but today’s ecological and climate justice movement realizes that people of every race and class must join together in a shared effort to live in loving relationship with each other and with the Earth upon which all life depends. In his stirring encyclical Laudato Si’, Pope Francis makes an impassioned plea for what he calls “integral ecology”: the recognition that everything is connected and that our social and environmental crises are not two separate issues but must be addressed together.16

A second ethical value that emerges when we perceive the world as pervaded by God’s love is reverence for nature. That’s what happened to me: as I recovered from my food addiction and learned to honor my body, listen to its needs, and live within its limits, I also began to connect with the natural world. I began to see that God loved not only my body – God also loved the whole “body” of creation. My prayer began to change. It was like turning my pocket inside out: whereas once I had found God mostly in silent, inward contemplation, now God began showing up around me – in the pond, the rocks, the willow tree. If you spend an hour gazing at a willow tree, after a while it begins to disclose itself, and to disclose God. I began to understand the words of poet Gerard Manley Hopkins: “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.”

For those of us who follow Jesus, it’s worth noting that Jesus lived close to the Earth. In the Gospels we find him walking along the seashore and up mountains, taking boats out on the lake, and spending weeks praying alone in the wilderness. His parables and stories are full of natural images: sheep, sparrows, seeds, lilies, water, fire, vines, and rocks. Jesus recognized the inherent sacredness not only of human beings but also of the whole created world, all of lit up with the presence of God. I wonder what it would be like to reclaim the kind of intimacy with the natural world that Jesus knew – to know, as he did, that “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows [God’s] handiwork” (Ps. 19:1).

St. Francis of Assisi followed in his footsteps, spending time in such intimate relationship with the elements and creatures of the natural world that he famously spoke of Brother Sun and Sister Moon. He knew that our identity doesn’t stop at our skin. Our boundaries are porous. My body is part of the Earth; the Earth is part of my body – a reality that Thich Nhat Hanh calls “inter-being.” Similarly, Robin Wall Kimmerer speaks eloquently about the reverence felt by Native Americans for the living world, “a world of being, full of unseen energies that animate everything.”17 We live in a sacred world of interrelationship and interdependence. We belong to each other. We depend on each other.

It’s easy to romanticize and sentimentalize St. Francis, but in an increasingly degraded natural world, what would it mean to take our place as humans who experience this kind of intimate connection with wild creatures and plants and all the elements that together create a balanced and healthy eco-system? Now is the time to reclaim the ancient understanding (which was never lost by indigenous peoples or by so-called “pagans”) that the natural world is sacred, that it belongs to God and is filled with God. Now is the time to dismantle the fossil-fuel mindset that treats the natural world as inert material, an object to exploit. The Earth, in fact, is a primary locus for our encounter with God. Such is the testimony of generations of Christian mystics and theologians, beginning with St. Paul (Romans 1:20). Destroying Earth is therefore a desecration, a sin against the Creator.

3. Third arrow: We practice sorrow, practice joy. Keeping our inner landscape alive is an essential spiritual practice when we’re tempted to shut down emotionally. Last March, when a front-page headline in big font reported that some scientists believe that a branch of the Gulf Stream is starting to weaken,18 I dropped what I was doing, lay face-down on the living room floor, and spent an hour weeping, arms outstretched. I knew that this announcement mattered. Twenty years before, at a weekend conference on climate change, I’d learned that the slowing or stopping of the Atlantic Ocean’s “conveyer belt” of currents is one of the tipping-points that could trigger far-reaching, dramatic, and very rapid changes in the Earth’s temperature, precipitation, and sea levels. Apparently, that moment had come. I needed to extend my arms over God’s good Earth. I wept with sorrow for her and for all of us.

Giving ourselves permission to experience our emotional response to a dying world is a basic practice to keep ourselves inwardly vital and alive. The Atlantic Ocean’s currents may be shutting down, but I don’t want to shut down! Falling in love with life, and with God, means consenting to be vulnerable. As C.S. Lewis points out, “To love at all is to be vulnerable.” So, we tune in to our own suffering and to the suffering of other beings – the suffering caused by injustice and cruelty, by climate change and ecological devastation. Clear-cut forests and forests going up in flames. Extinct species. Insect apocalypse. Vanishing topsoil. Disappearing wetlands. Areas of the Amazon rainforest that no longer sequester carbon but actually release it. Ocean dead zones and stalling currents. Tipping points that threaten to propel us into chaos.

How do we pray with this? Our broken-hearted prayer may need to be expressive and embodied, visceral and vocal. We may need to drum, stamp, or wail. How else can we pray with our immense anger and grief? How else can we pray about ecocide, about the death that humanity is unleashing upon Mother Earth and upon ourselves? How else can we break through our inertia and despair, so that we don’t shut down and go numb?

I am thankful to Joanna Macy for encouraging us to honor our pain for the world and to realize that our pain springs from love. The symbol in Christianity for the meeting-place of pain and love is the Cross: crucifixion is the place where evil, malice, ignorance, and confusion are perpetually met by the love of God. So, one place I go in prayer when I am overwhelmed by the pain of the world is to the cross of Christ. As I experience it, the cross of Christ is planted deep within me, and at the cross I can pour out everything that is in me – anger, fear, grief, guilt – for I trust that at the cross, everything is met by the forgiving love of God.

Crucifixion is the place where God breaks through our numbness and denial. At the foot of the cross, we can finally face and bear all that we know about the pain of the world, and where God in Christ can hold and bear whatever we cannot bear ourselves. I imagine this practice being something like the practice of tonglen in Tibetan Buddhism: I breathe in the pain and, breathing out, I release it into the cross of Christ.19 I can’t bear the pain, but Christ can bear it. I can’t forgive it all, but Christ can forgive it. Whatever I need to feel and express, all of it is met with compassion. Along the way, everything transforms, as if becoming good compost. In this time of ecological crisis, Christians may need to take hold of the power of the cross as never before.

We are blessed that many faith traditions provide rituals and practices for accessing and processing grief. In my own tradition, lament is an ancient form of prayer found in the Book of Lamentations, the Psalms, the prophets, and the words and actions of Jesus. “Blessed are those who mourn,” he says in one of his great teachings, the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:4), and several Gospel stories portray his grief. He wept at the death of Lazarus, he wept over the city of Jerusalem, and he cried out to God on the cross, using the lament of Psalm 22. When we lament, we share our anguish with God, and we dare to feel what is breaking God’s heart.

And lament can be empowering. Jewish and Christian theologians from Abraham Heschel to Walter Brueggemann (and many more) point out that lament is the beginning of criticism of an unjust social order. The powers-that-be would prefer that we stay too busy, too distracted and numb to feel our emotional responses to what unjust systems are doing to human beings and to the planet on which all life depends. What Brueggemann calls “the capacity and readiness to care, to suffer, to die, and to feel”20 is the enemy of a society built on refusing to hear the cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor. Grieving is how we begin to challenge an unjust social order, cultivate hope, and open a space for bold actions commensurate with the crisis we are in.

So, let’s dare to lament! Let’s tell the truth: our hearts are breaking, because that’s how fiercely we love this beautiful, broken world that God entrusted to our care. And let’s dare to rejoice, as well! Let’s celebrate joy, wherever we find it – in the curl of an autumn leaf; in a word of appreciation, given or received; in the sensation of bare feet on soft grass or the sound of a loon letting loose her wild call. The practice of joy balances the practice of sorrow, keeping our hearts wide open, making room for everything.

4. Fourth arrow: We take bold action for healing. The U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change asserts that, in order to preserve a habitable, governable world, we must transform our society and economy away from fossil fuels at a scale and speed that are historically unprecedented. Energy companies already possess a pool of fossil fuel that is five times larger than the amount of fossil fuel that would catapult the global climate into catastrophic, runaway change if that fuel were burned. We must fight to keep that carbon in the ground, where it belongs, for the only way to avoid shooting past that 1.5º or 2º degree Celsius cap that protects us from runaway climate change is to keep 80% of known reserves of coal, gas and oil in the ground, to transition quickly to renewable sources of energy like sunshine and wind, and to protects forests, which sequester carbon.

Hearing this, we may shrink back, telling ourselves: That will never happen. We’re too far gone. It’s too big for me to deal with.

There is a Bible passage, often read at weddings, which Christian mystics interpret as God speaking to the soul. It begins like this: “Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away” (Song of Solomon 2:10). Like a tenacious lover, God summons us: “Arise.” From what must we arise? Maybe we hear: Arise from apathy, numbness, and fear. Arise from hopelessness: I will give you strength. Arise from loneliness: I am with you. Arise and come away: leave the cult of death. Leave the path of folly. Abandon the lie that your efforts are useless. Come with me and join the dance of life. Come be a sacred warrior, a warrior for the common good. I will help you find your place in the great struggle to protect life and to build a more just society.

“But” we may protest, feeling helpless before the horrors of the world, helpless before injustice and needless suffering. “Who am I? I have no power.”

Arise.

“What can I do? What can any of us do? It’s too late to make a difference!”

Arise.

“I don’t have time. I don’t have energy. I’ve got other things to deal with.”

Arise.

The voice of love is like that. It may be soft, difficult to hear in a noisy world, but it is persistent. It may be subtle, but it never goes away. The love that created the universe, the love that stirs in our depths, the love that awakens our hearts – that holy love sends us out into the world to become beacons of light, warriors for truth, and protectors of life. I may have a thousand and one reasons to dodge love’s call, but then it comes again, that voice: Arise. I love you. I need you. I am calling from the trees, from the wind, from the very stones beneath your feet. I am calling from the orcas and the salmon, from the black bear and the mountains, from the fig trees and the vines. I am calling from the people already suffering from a wounded Earth and a changing climate. I am calling from the future, from those who will inhabit this planet long after you are gone and who depend on you to leave them a habitable world. Arise, my love, and join the effort to save our precious planet. Arise!

Roused by that holy voice, we receive fresh strength to renew the face of the Earth. And we arise, joining with indigenous leaders to protect the water and the land, joining with activists to stop new pipelines, joining with city-dwellers to renew communities crushed by poverty and racism, joining with young and old to plant new forests. We use our voices and our votes as we fight to make it politically possible to do what is scientifically necessary. We support the movement to hold polluters like Exxon and Koch Industries financially and legally liable for the damages they knowingly caused and continue to cause. We lobby for policies that support renewable energy, clean green jobs, and a just transition that meets the needs of poor and low-wealth communities and communities of color. If we have financial resources, we divest from fossil fuels. If we are college graduates, we push our alma mater to divest. Maybe we join the growing numbers of resolute people who carry out peaceful civil disobedience and we put our bodies on the line. Together we need to grow the boldest, most visionary, inclusive, powerful, hope-filled, hands-on, feet-on-the-ground, shoulder-to-the-wheel political and social movement that humanity has ever seen.

I am strengthened when I remember that I and other Christians are called to bear witness to resurrection, to a love that transcends death. In our baptism, we are immersed in the waters of death. We die in Christ and we die with Christ. And then we rise with Christ: from now on, our death is done with. It is behind us. We have died with Christ and are now alive in Christ. To whatever extent we can take this in, we are set free from anguish and anxiety, set free to love without grasping, possessiveness, or holding back. In the early centuries of the Church, Christians were called “those who have no fear of death.”21 That inner fearlessness, rooted in the love of God, empowered the early Christians to resist the unjust powers of the state: early on they were charged with “turning the world upside down” (Acts 17:6) and “acting contrary to the decrees of the emperor (Acts 17:7). Their inner liberation gave them courage to resist the forces of death and destruction, and to obey God rather than any human authority (Acts 5:29).

I don’t know if we will avert climate chaos. But I do know that every degree of temperature-rise matters; indeed, every tenth of a degree of temperature-rise matters. So, we throw ourselves wholeheartedly into serving life, and, whatever comes, we put our trust in the divine love that never dies. As one ancient Hebrew prophet put it: “Though the fig tree does not blossom, and no fruit is on the vine; though the produce of the olive fails, and the fields yield no food; though the flock is cut off from the fold, and there is no herd in the stalls, yet I will rejoice in the LORD; I will exult in the God of my salvation. GOD, the Lord, is my strength” (Habbakuk 3:17-19a). The same conviction is expressed in a prayer in the Episcopal burial service: “All of us go down to the dust; yet even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.”22

I stake my life on love’s four arrows: love within, love beyond, love that willingly suffers, and love that takes action and refuses to settle for a killing status quo. These four arrows pull us out of the box of ordinary consciousness, the box of business as usual, and into a larger, more connected space: a space of healing and transformation.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Leah Schade and Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, ed., Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). The book includes study questions and spiritual practices.

2. “Sarah Doering: Beloved IMS Teacher, Friend and Benefactor—1926-2018,” https://www.dharma.org/sarah-doering-beloved-ims-teacher-friend-and-benefactor-1926-2018/

3. The Empty Bell, http://www.emptybell.org/

4. Robert Lentz, OFM, “Compassion Mandala,” https://robertlentzartwork.wordpress.com/2012/06/19/httpswww-trinitystores-comstoreart-productsrlcmm/

5. Rev. Cameron Trimble, “Mistakes about God,” Piloting Faith, Nov. 2, 2021, https://camerontrimble.com/category/meditation/

6. The solution posted on Wikipedia looks like a bow and arrow – an association that figures into this essay. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thinking_outside_the_box

7. Charles Wesley, “Love divine, all loves excelling,” Hymn 657, The Hymnal 1982 (New York: The Church Hymnal Corporation, 1985).

8. Anthony, quoted by Athanasius of Alexandria, in The Roots of Christian Mysticism, Olivier Clément (London: New City, 1993), 204.

9. Brother Lawrence of the Resurrection, The Practice of the Presence of God, translated with an intro. By John J. Delaney (Garden City, New York: Image Books, Doubleday, 1977), 68, 69.

10. To be more exact, “An Outline of the Faith” in the Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer defines sacraments as “outward and visible signs of inward and spiritual grace, given by Christ as sure and certain means by which we receive that grace” (New York: The Church Hymnal Corporation, 1979), 857.

11. Jean-Pierre de Caussade, The Sacrament of the Present Moment, trans. by Kitty Muggeridge, intro. by Richard J. Foster (New York: HarperCollins, 1989).

12. Henri J. M. Nouwen, The Life of the Beloved: Spiritual Living in a Secular World (New York: Crossroad, 1992).

13. Damian Carrington, “‘Climate apartheid’: UN expert says human rights may not survive,” The Guardian, June 25, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jun/25/climate-apartheid-united-nations-expert-says-human-rights-may-not-survive-crisis/

14. Nathalie Baptiste, “Climate Gentrification: Coming to a Community Near You,” Mother Jones, September 5, 2019, https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2019/09/climate-gentrification-coming-to-a-community-near-you/

15. Hop Hopkins, “Racism Is Killing the Planet,” June 8, 2020, https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/racism-killing-planet

16. Pope Francis, Laudato Si – Praise Be to You: On Care for Our Common Home, 2015, par. 139.

17. Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2013), 49.

18. Moises Velasquez-Manoff and Jeremy White, “In the Atlantic Ocean, Subtle Shifts Hint at Dramatic Dangers,” New York Times, March 2, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/03/02/climate/atlantic-ocean-climate-change.html

19. In my book, Christ’s Passion, Our Passions (Cambridge, MA: Cowley Publications, 2002), pp. 9-13, I describe a way of prayer I call “Grounding in the Cross,” based on Macy’s presentation of tonglen.

20. Walter Brueggemann, The Prophetic Imagination (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1978), 41.

21. Olivier Clement, The Roots of Christian Mysticism (London: New City, 1993), 107.

22. Book of Common Prayer, 499.