Fasting from carbon

I am blessed to be with you this morning. My husband and I now come to Grace-St. Paul’s whenever we visit Tucson, and I am grateful to be with you again. This is a special place: I feel the Holy Spirit here. Thank you, Steve, for inviting me back to this pulpit.

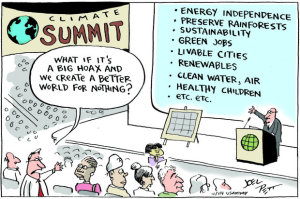

To say just a word about myself: after 25 years of parish ministry, I now serve as Missioner for Creation Care in the Diocese of Western Massachusetts. My dream is to help create a wave of religious activism to protect the web of life that God entrusted to our care. So I travel around, preaching and teaching and leading retreats about God’s love for this precious planet and its inhabitants, human and other-than-human, and the need to take action to express our faith. My particular concern is the climate crisis, so you can probably imagine my delight when I learned a few weeks ago that the couple who funded the first two years of my ministry raised the money by selling off their oil stocks. This is happy news to someone who believes, as I do, that divesting from fossil fuels is an expression of our moral values and will help propel a shift to clean energy. So here we are in the second Sunday in Lent, a season for renewing our lives in response to the love of God. Thanks to the passage from Genesis, today we have Abram standing at our side, an old man who, along with his wife, was landless, childless, without an heir. The door to his future was completely closed, shut tight, locked, and throw away the key. Nothing good lay ahead. Then God spoke to Abram in a vision and made a promise, the kind of promise that God made to a whole line of prophets, one after another: the door to the future was open. Through the grace of God, Abram’s life would bear fruit; he would bring forth life; he would convey blessings that would reach far into the future, blessings as countless as the stars. And Abram responded with faith. He trusted in God’s promise. He stepped out into an unknown and open future, trusting that God would guide him and that God would make him a vehicle or channel for new life. Today is a good day to stand with our faithful brother Abram and to reaffirm our trust in God’s promise that even when the future looks bleak or chaotic, even when we see no way forward, God is with us. God will open a path where there was no path, provide a way where there was no way, and pour divine hope into our hearts when our own hope is gone. Heaven knows there are reasons to fear for the future. The web of life is unraveling before our eyes. In just 200 years – a blink in geologic time – human beings have burned so much coal, gas, and oil and released so much heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that atmospheric levels of CO2 are higher than our species has ever experienced before. So far that extra CO2 has forced the average global temperature to rise about one degree. That may not sound like much, but what’s so worrisome to scientists is that this process is happening so fast. Already oceans are heating and becoming more acidic; tundra is thawing; ice caps are melting; sea levels are rising; coral reefs are dying; massive droughts are spreading in some places and heavy rains intensifying in others. We’re on the edge, or in the midst, of what some experts call the sixth major extinction event on this planet. 2015 was the hottest year on record, shattering the record set just the year before. We know that the situation is urgent. We know we have only a short time in which to avert a level of climate disruption that would render the world ungovernable and possibly uninhabitable within the lifetimes of our children and our children’s children. The World Bank – hardly a leftist organization – recently warned that unless we quickly rein in greenhouse gas emissions, climate change will drive 100 million people into extreme poverty – extreme poverty – in the next 15 years. Just imagine for a moment the human suffering and social upheaval that this would engender worldwide. We know we can do better than that. And as people of faith we refuse to stand idly by and to let business as usual destroy human communities and destroy life as it has evolved on the planet. As Pope Francis so beautifully explained in his landmark encyclical, Laudato Si – in a message that was picked up and amplified by Anglican, Jewish, Muslim, and many other religious voices the world over – we bear a moral and spiritual responsibility to respond boldly to the climate crisis. Lent invites us to come back into balance, to align our lives with our deepest intention, and to make the changes we need to make in order for God’s love to be manifest more fully in our lives. Today, in the presence and power of God, and with Abram at our side, we dare to ask some big questions: Through the grace of God, how can my life bring forth new life? How can I contribute to a better future? How can I live so that my life becomes a blessing to those who come after me? As Ella Fitzgerald once put it, “It isn’t where you came from, it’s where you’re going that counts.” You know, there are many ways to be healers in the world, many ways to help our neighbors. But regarding climate change, here come three suggestions. One: sign up online for the Ecumenical Lenten Carbon Fast. During Lent, we seek to restore the limits that give life. Let’s you and I learn how to fast from carbon. Let’s you and I learn together how to make choices that cut back dramatically on our use of fossil fuels. This is an honorable, and I would argue, a necessary, Lenten practice. When you sign up for the Ecumenical Lenten Carbon Fast, you receive a daily email with inspirational reflection and a specific action step to reduce your personal consumption of dirty energy. Right now the fast is being carried out by thousands of Christians who care for God’s Creation. Two: write a postcard to your members of Congress. After the service, stop at the table for Citizens Climate Lobby and pick up some postcards. You might think that writing a letter or postcard to your member of Congress is a waste of time, but it’s not: your representatives probably have no idea that you care about climate change and that you’re tracking what they’re doing. And Citizens Climate Lobby is pushing for a way to price carbon that will get us off fossil fuels, create new jobs, and accelerate a transition to a new economy based on clean, renewable sources of energy, like sun and wind. Last summer I joined scores of other faith leaders to lobby on behalf of Citizens Climate Lobby in Washington, D.C. We didn’t push for carbon pricing because we were Democrats, or because we were Republicans, or because we were socialists or members of the Green Party. It wasn’t politics that propelled us to support carbon pricing. It was faith: faith in a God who utterly loves us and all Creation, faith in a God who envisions a healthy, just, and sustainable society, faith in a God who wants our lives to be a blessing to the vulnerable poor and to those who come after us. Three: go to the Website 350.org, sign up to receive emails, and build the global climate movement. 350.org is the grassroots non-profit that is helping to create a wave of global resistance to keep coal, gas, and oil in the ground, where they belong. This coming May, actions will be held in places all over the world to “shut down the world’s most dangerous fossil fuel projects and support the most ambitious climate solutions.” Already the movement to keep fossil fuels in the ground is gaining momentum. People are blockading oil trains and protesting the construction of new pipelines; thousands of so-called “kayaktivists” took to the water in Seattle to block an oil-drilling rig; and two men in a lobster boat near Cape Cod disrupted the delivery of 40,000 tons of coal. Just this week, beloved writer Terry Tempest Williams took part in an auction in Salt Lake City that was selling off leases for oil and gas drilling on public lands. As a climate protester, she bought up land rights on a parcel near Arches National Park in Utah in an effort to prevent any drilling. Later she commented, “It has deeply shaken my core as an American citizen to watch these beautiful, powerful public lands that are all of ours, and our inheritance, being sold for $2 an acre, $3 an acre… I’m both heartsick and heartbroken and outraged.” Yes, it can be heartbreaking to take part in the struggle to stabilize the climate and to heal our relationship with the Earth. But the pain we feel is an expression of love, and love is what sustains us, and guides us, and will see us through. So I invite you to take up my three suggestions: to join the Ecumenical Lenten Carbon Fast; to sign postcards to your legislators on behalf of Citizens Climate Lobby; and to join 350.org and the global climate movement. As people of faith, we’re here for the long haul. We’re not going away. We’re going to keep fighting for a future that runs on clean energy like sun and wind. We’re going to keep fighting for a society and an economy that leave no one out. As Pope Francis reminded us, the cry of the Earth is intimately connected with the cry of the poor. We hear that cry. We share that cry. And we intend to answer it, by divestment and direct action, by voting and lobbying, by making personal changes in our lifestyle and, perhaps, by engaging in peaceful civil disobedience. A new world is on the horizon, and we hope to act like midwives, helping that new world to be born. We hope to act like Abram, trusting in God’s promise of new life. And we hope to act like Jesus, who when Herod threatened to kill him, refused to be intimidated or deterred. Despite all the forces arrayed against him, Jesus continued to heal and to set free. He refused to be stopped. “Today,” he said, “tomorrow, and the next day I must be on my way” (Luke 31:33 ). And so it is for us. We, too, must be on our way — on Jesus’s way — today, tomorrow, and the next day. Who knows what God in Christ will be able to do through us, now and in the days ahead?