Keep it in the (holy) ground

It is good to be here at St. Paul’s and to worship with you this morning. My name is Margaret Bullitt-Jonas and I have a quite unusual ecumenical position as Missioner for Creation Care in the Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts and in the United Church of Christ across Massachusetts. I travel around, preaching and leading retreats about God’s love for this precious planet and its inhabitants, human and other-than-human. My dream is to help create a wave of religious activism to protect and heal the web of life that God entrusted to our care. So I want to thank you for your leadership. You’ve installed solar panels, you’ve formed a Green Team, some of you have read and studied Pope Francis’ landmark encyclical, Laudato Si’, and I’m told that many of you want to explore how to connect with nature as a spiritual practice.

Preachers around the country are marking Earth Day today and speaking about the glory and the vulnerability of God’s Creation. How wonderful that our readings this morning include Psalm 148, that powerful song of praise to God from the heights and depths of creation, from every element and creature, from every nook and cranny: “Hallelujah! Praise the LORD from the heavens; praise God in the heights… Praise God, sun and moon; praise God, all you shining stars… Praise the LORD from the earth, you sea-monsters and all deeps; Fire and hail, snow and fog; tempestuous wind, doing God’s will; Mountains and all hills, fruit trees and all cedars…Young men and maidens, old and young together. Let them praise the Name of the LORD…” (Psalm 148:1,3,7-9,12,13) This kind of ecstatic poetry springs from a perception that everything is connected, everything is alive with Spirit, everything is held together by a divine presence that sustains and upholds all things. That’s the vision of St. Francis of Assisi, whose “Canticle of the Sun” proclaims: “Praise be my Lord for our brother the wind, and for air and cloud, calms and all weather, by which you uphold life in all creatures.” That’s the vision of poets like Gerard Manley Hopkins, who wrote, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.” That’s the vision of theologians like Martin Luther, who said, “God writes the Gospel, not in the Bible alone, but also on trees, and the flowers and the clouds and stars.” That’s the vision, I believe, of Jesus himself, a man who lived close to the Earth, whose ministry began by immersion in a river and who prayed and lived and walked countless miles outdoors. In his parables and stories, Jesus talked about God in terms of natural things: seeds and sparrows, sheep and lilies, rivers, wind, and rocks. Jesus was immersed in the sacredness of the natural world and it’s no wonder that in our sacraments we, too, make contact with simple earthy things: with bread, wine, water, and oil. We trust that God is in these things – that when we take in the consecrated bread and wine of the Eucharist, we take in God’s presence. This powerful perception that the natural world is holy awakens in some of us a deep response. We want to ensure that God’s sacred creation is treated with reverence. We feel a growing resolve to take action to heal and reconcile and restore the beautiful world that God entrusted to our care. Heaven knows that God’s creation is crying out for help. The web of life is unraveling before our eyes. In just 200 years – a blink in geologic time – human beings have burned so much coal, gas, and oil and released so much heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that atmospheric levels of CO2 are higher than our species has ever experienced before. So far that extra CO2 has forced the average global temperature to rise about one degree. That may not sound like much, but what’s so worrisome to scientists is that this process is happening so fast. Already oceans are heating and becoming more acidic; tundra is thawing; ice caps are melting; sea levels are rising; coral reefs are dying; massive droughts are spreading in some places and heavy rains intensifying in others. We’re on the edge, or in the midst, of what some experts call the sixth major extinction event on this planet. March 2016 was the hottest month ever recorded, which crushed the record set in February, which crushed the record set in January, which crushed the record set in December. A recent article in the Washington Post bears the title, “Scientists Are Floored by What’s Happening in the Arctic Right Now.” We know that the situation is urgent. We know we have only a short time in which to avert a level of climate disruption that would render the world ungovernable and possibly uninhabitable within the lifetimes of our children and our children’s children. The World Bank – hardly a leftist organization – recently warned that unless we quickly rein in greenhouse gas emissions, climate change will drive 100 million people into extreme poverty – extreme poverty – in the next 15 years. Just imagine for a moment the human suffering and social upheaval that this would engender worldwide. When I look around, I see a planet in peril, but – thanks be to God! – I also see person after person reaching deep into their souls and then standing up to join the struggle to re-weave the fabric of life and create a just and sustainable future. I see a wave of religious protest and activism rising up around the world, propelled in part by the release of Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’, which makes a powerful connection between the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor. I see people rising up for life, refusing to settle for a killing status quo, and proclaiming with one voice that climate change is a spiritual and moral issue that must be tackled without delay. Just think of all the signs we see of a new social order being born. We see people blocking the path of new fracked gas pipelines and being arrested for civil disobedience as they read aloud from Pope Francis’ encyclical. We see people lobbying for a fair price on carbon, so that we can build a clean green economy that provides decent jobs and improves public health. We see our own Episcopal Church deciding to divest from fossil fuels, since it makes no financial or moral sense to invest in companies that are ruining the planet. We see new coalitions being formed and new alliances being forged, as people realize that the environmental crisis is closely connected with the social crises of poverty, income inequality, and racial injustice. Right here in Massachusetts we have a strong grassroots climate action network, 350Mass for a Better Future, which has nodes across the state. When you sign up for the weekly newsletter or attend a node meeting near you, you’ll be hooked into a vibrant local effort. I’m also part of a new group, Massachusetts Interfaith Coalition for Climate Action, or “MAICCA” for short, which is bringing together Christians, Jews, Quakers, Unitarians, and people of all religious traditions to push for legislation that supports climate justice. Together we are fighting to keep fossil fuels in the ground and to accelerate a transition to clean, safe, renewable sources of energy, such as sun and wind, that are accessible to all our communities, including those that are low-income or historically under-served. As climate activist Bill McKibben has pointed out, “The fight for a just world is the same as the fight for a livable one.” The Church was made for a time like this – a time when God calls human beings to know that we belong to one Earth, that we form one human family, and that God entrusted the Earth and all its residents to our care. We may live in a society where we’re told that pleasure lies in being self-centered consumers who grab and hoard everything we can for ourselves and the devil take the hindmost, but we know the truth: our deepest identity and joy is found in being rooted and grounded in love and in serving the common good. As Jesus tells us this morning, “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). That love extends not only to our own little group nor only to our family and friends. It extends not only to our town, to our nation, nor only even to other human beings – no, that love extends outward to embrace and fill the whole glorious creation, including mountains and hills, trees and beetles and stars. God has placed us in and made us part of a miraculous, intricate, and living world, and when we listen closely we will hear what the psalmist hears: a shared song of praise to our Creator. I’ll close with the words of a contemporary song that echoes Psalm 148. Written by Kim Oler, the song (“Blue Green Hills of Earth”) is part of Paul Winter’s “Missa Gaia.” I offer these words to God as a prayer – a prayer of gratitude for the gift of life, and a prayer of hope that we can protect that life and pass it on to future generations. For the earth forever turning; for the skies, for every sea; to our Lord we sing, returning home to our blue green hills of Earth. For the mountains, hills, and pastures in their silent majesty; for all life, for all nature, sing we our joyful praise to Thee. For the sun, for rain and thunder, for the land that makes us free; for the stars, for all the heavens, sing we our joyful praise to Thee.

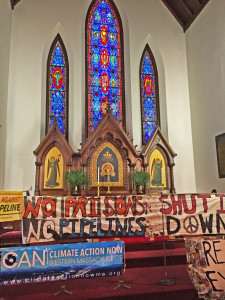

As a Christian climate activist, I found it stirring to realize that the rally was taking place on the eve of Palm Sunday, the day that Christians around the world step into Holy Week. Here were the stately altar and lectern arrayed in cloths of traditional red colors for tomorrow’s service, yet here, too, were banners draped across altar, pulpit and lectern, crying out in large letters: “No Prisons, No Pipeline. Shut It Down,” “Respect Existence, Expect Resistance,” and “Love Will Win.”

As a Christian climate activist, I found it stirring to realize that the rally was taking place on the eve of Palm Sunday, the day that Christians around the world step into Holy Week. Here were the stately altar and lectern arrayed in cloths of traditional red colors for tomorrow’s service, yet here, too, were banners draped across altar, pulpit and lectern, crying out in large letters: “No Prisons, No Pipeline. Shut It Down,” “Respect Existence, Expect Resistance,” and “Love Will Win.”