The day before I got arrested, I woke up singing.

“Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around, turn me around, turn me around.

Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around.”

Resolve filled me as I sang my way through the tasks of the day, preparing for the morrow. Do you want to gather your courage? Lift your spirits? Find your true north? Stay the course? You get there by singing.

On the day I was arrested, I sang.

We all sang.

On May 25, a crowd of nearly 100 people gathered under a blue sky in a neighborhood of Boston, near the West Roxbury site of the “metering and regulating” station for Spectra Energy’s West Roxbury Lateral gas pipeline. We came to pray about our commitment to keep fossil fuels in the ground. We came to put our bodies on the line: sixteen leaders of different faith traditions were readying for civil disobedience to stop the pipeline. And we came to sing.

Shoshana Meira Friedman, Assistant Rabbi for Engagement at Temple Sinai in Brookline, took the lead in organizing our act of interfaith prayer and protest. In her strong soprano, accompanied by guitar, she launched the event with an anthem by Holly Near, “We are a gentle, angry people and we are singing, singing for our lives. We are all in this together, and we are singing, singing for our lives.”

Once you understand the urgency of avoiding climate chaos – once you grasp the need to keep fossil fuels in the ground, including natural gas – once you realize that climate change is already starting to unravel the web of life and that it harms the poor first and hardest – then you know it’s no exaggeration to say that we are singing and fighting for our lives.

And sing we did, updating the words of various songs as we went along.

“Ain’t gonna let no pipeline turn me around, turn me around, turn me around…”

“Ain’t gonna let no coal mine turn me around…”

“Ain’t gonna let the folks at FERC turn me around…” – “FERC” being the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, an agency notorious for rubberstamping pipeline industry requests for new pipelines, even if those pipelines cut through conservation areas, or leak methane (a greenhouse gas far more potent and deadly in the short term than carbon dioxide), or carry highly-pressurized, potentially explosive gas into an urban neighborhood like West Roxbury, alongside a quarry engaged in active blasting.

“Ain’t gonna let no fear turn me around…”

When we reached this verse, I planted my feet more firmly on the ground and raised my head. Of all the verses, this one is the most far-reaching. Fear is what prevents us from stepping outside our comfort zone and taking part in the struggle for a more just and sustainable society – for starters, fear of the unknown, fear of failure, fear of loss, fear of ridicule, and fear of bodily harm. The power of ordinary people seems puny when compared with the power of the political and corporate behemoths that rule the world. Why stick your neck out?

Yet there is no message that runs more frequently through the Bible than the message: “Fear not.” We hear it in the Old Testament: “Do not be afraid, Abram, I am your shield” (Genesis 15:1). “Do not be afraid, stand firm, and see the deliverance that the LORD will accomplish for you today” (Exodus 14:13). “The LORD is my light and my salvation; whom then shall I fear?” (Psalm 27:1). We hear it in the New Testament: “Do not be afraid: for see – I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people” (Luke 2:10). “Take heart, it is I: do not be afraid” (Mark 6:50). “Perfect love casts out fear” (1 John 4:18).

The first followers of Jesus clearly tapped into a source of love and power that gave them strength to challenge injustice. Apparently there were two basic ways of identifying Christians: you would know Christians by their love (John 13:35) and you would know them by their commitment to “turning the world upside down” (Acts 17:6). Not surprisingly, the first followers of Jesus seem to have spent a fair amount of time in jail. As my bishop, Douglas Fisher, recently put it, “When we follow Jesus, stuff is going to happen.” How would Christianity change today if it became normative for Christians to risk arrest in acts of peaceful resistance to fossil fuels?

The sixteen of us preparing to risk arrest came from a variety of denominations and traditions – American Baptist, Buddhist, Episcopal, Hindu, Jewish, Presbyterian, United Church of Christ, and Unitarian Universalist. We represented a range of diverse religions, yet all of us were drawing upon a holy power greater than our selves. All of us were rooted in a reality that transcends the rules and structures of this world. All of us were fired by the vision of a better world, by faith in the human spirit, and by faith that God would guide us to courageous and visionary action.

And all of us were willing to step past our fear and to put our bodies on the line.

Music helped us do that – so, after holding a worship service in front of the “metering and regulating” station, we made our way in procession up the street, following Rabbi Shoshana and singing all the way.

“The tide is rising, and so are we.

The tide is rising, and so are we.

The tide is rising, and so are we.

This is where we are called to be.

This is where we are called to be.”

(To watch a splendid videotape of this climate anthem written by Shoshana Meira Friedman and her husband Yotam Schachter, and performed at Washington National Cathedral by Rabbi Shoshana and Rev. Fred Small, visit here.)

When we reached the intersection of Grove and Washington Streets, we saw ahead of us the open trench where construction workers were installing the pipeline. The procession paused briefly on the sidewalk for a quick consultation and a quick in-breath of courage. Then we made a dash for the pit. I slid under the barrier and scrambled to a seated position, my legs dangling over the 12-foot trench.

There we stayed, the sixteen of us, sitting on the edge of the trench and taking turns calling out prayers and giving short, impassioned sermons about the moral call to stop climate change. Using prayers I’d drafted, we prayed for the construction workers, the police, and the neighborhood.

A Prayer for the Spectra Workers: Gracious God, we remember before you everyone who labors, and especially we pray for everyone working here at this construction site for Spectra Energy. We pray for their safety and well-being, and we pray for their families and loved ones. We thank you, God, for the dignity of work. We pray that, as our economy makes a swift transition from fossil fuels to clean, safe, renewable energy you will give us strength and resolve to ensure that workers everywhere share in a clean energy economy and enjoy fulfilling, safe, and well-paid jobs.

Prayer for the Police: Almighty God, we commend to your gracious care and keeping all the men and women who serve in law enforcement. Thank you for their calling to public service. Watch over all police officers; protect them from harm in the performance of their duty; give them compassion, good judgment and wisdom, and fill their spirit with a balance of strength and love.

Prayer for this Neighborhood: O God, you have bound us together in a common life. We pray for the neighborhood of West Roxbury: for its safety, beauty, and good health. We pray for all communities that are divided over whether and how to end our use of fossil fuels. Help us, in the midst of our struggles for a just and sustainable economy, to confront one another without hatred or bitterness, and to work together with mutual forbearance and respect.

When the police chief gave a five-minute warning that we would be arrested if we didn’t move, we stayed put. Instead, we read aloud together the words of Buddhist activist Joanna Macy (World as Lover, World As Self: Courage for Global Justice and Ecological Renewal, Parallax Press, 2007):

“When you make peace with uncertainty, you find a kind of liberation. You are freed from bracing yourselves against every piece of bad news, and from constantly having to work up a sense of hopefulness in order to act – which can be exhausting. There’s a certain equanimity and moral economy that comes when you are not constantly computing your chance of success. The enterprise is so vast, there is no way to judge the effects of this or that individual effort – or the extent to which it makes any difference at all. Once we acknowledge this, we can enjoy the challenge and the adventure. Then we can see that it is a privilege to be alive now in this Great Turning, when all the wisdom and courage ever harvested can be put to use.”

By the time the police came to put us in handcuffs and escort us to the vans, we were singing again.

“The tide is rising, and so are we.

The tide is rising, and so are we.

The tide is rising, and so are we.

This is where we are called to be.

This is where we are called to be.”

Even as we sat, handcuffed, in the dark recesses of the van, waiting to be driven to the police station, we could hear our supporters singing outside, as well as snatches of the impassioned, impromptu sermon being delivered on the edge of the pit by our friend Rev. Mariama White-Hammond.

It’s no wonder that singing filled the lives of our ancestors in the faith (see Matthew 26:30, 1 Corinthians 14:26, Ephesians 5:19, Colossians 3:16). Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom (2 Corinthians 3:17). And where there is freedom or the longing to be free, you will find people singing.

As of today, there have been 85 arrests at the West Roxbury Lateral pipeline site. I am sure there will be more. Resist the Pipeline is organizing protests and providing training in civil disobedience. Better Future Project is planning a major march and action to stop new gas pipelines on July 14-18, which will include direct action at the pipeline construction in West Roxbury (for information and to register, visit here).

Meanwhile, fossil fuel resistance is growing worldwide. In recent weeks, thousands of people on six continents took coordinated, strategic action to stop fossil fuels. Through Clergy Climate Action, a new project of Climate Disobedience Center, clergy of many faiths have signed a pledge to participate in peaceful direct action to resist new fossil fuel development. I invite all religious leaders to endorse our statement. Here is the closing paragraph:

“As religious leaders, we oppose further development of fossil fuel resources and infrastructure in our nation. We envision a livable climate for our communities, for the poor, for our children, and for all life. We call for immediate and robust public investment in climate solutions, including large-scale renewable energy. We will resist new fossil fuel development through joyful, faithful, spirited, and nonviolent direct action.”

The day after I got arrested, I woke up singing.

“We will not give up the fight, we have only started, we have only started, we have only started.

We will not give up the fight. We have only started.”

The 16 religious leaders arrested in West Roxbury on May 25, 2016:

Rabbi Shoshana Meira Friedman, Assistant Rabbi, Temple Sinai, Brookline

Rev. Dr. Jim Antal, Conference Minister and President, Massachusetts Conference, United Church of Christ

Rev. Anne Bancroft, Minister, Theodore Parker Unitarian Universalist Church, West Roxbury

John Bell, Buddhist Dharma Teacher, Plum Village Tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh, Belmont

Rev. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, Ph.D., Missioner for Creation Care, Episcopal Diocese of Western Mass. & Mass. Conference, United Church of Christ

Rev. Heather Concannon, Assistant Minister of Youth and Families, Unitarian Universalist Area Church at First Parish, Sherborn

Cantor Roy Einhorn, Temple Israel of Boston

Rev. Rebecca Froom, Minister, United First Parish Church (Unitarian), Quincy

Rev. John Gibbons, Minister, The First Parish in Bedford

Dr. Rajesh Kasturirangan, South Asian Center, Cambridge

Rev. Rob Mark, Pastor, Church of the Covenant, PCUSA & UCC, Boston

Rev. Dr. Ian Mevorach, Co-founder and Minister of Common Street Spiritual Center in Natick

Rev. Martha Niebanck, Minister Emerita, First Church of Brookline

Rev. Elizabeth Nguyen, Leadership Development Associate for Youth and Young Adults of Color, Unitarian Universalist Association

Rev. Fred Small, Minister for Climate Justice, Arlington Street Church, Boston

Rev. Rali Weaver, Minister, First Church and Parish in Dedham

Additional links:

If you read only one article this month about climate change, read Bill McKibben’s essay on the chemistry and politics of fracking, “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Chemistry.” “Our leaders thought fracking would save our climate. They were wrong. Very wrong.”

For an eloquent essay on the West Roxbury protest and why people of faith – indeed, all people – need to interrupt business as usual, read Wen Stephenson’s essay, “A Prayer for West Roxbury – and the World”

Wen Stephenson writes for The Nation and is the author of What We’re Fighting for Now Is Each Other: Dispatches From the Front Lines of Climate Justice (Beacon)

The Boston Globe, “Police break up protest at pipeline construction site”

The Jewish Advocate, “Clerical activism, public safety, climate change”

Mass. Conference, United Church of Christ, “Antal among 16 clergy arrested at pipeline protest”

Metro, “Religious leaders arrested in protest of controversial natural gas pipeline”

Wicked Local, Natick, “16 clergy members arrested at West Roxbury Lateral gas pipeline protest”

[http://natick.wickedlocal.com/news/20160525/16-clergy-members-arrested-at-west-roxbury-lateral-gas-pipeline-protest

Universal Hub, “Clergy arrested at West Roxbury pipeline protest”

Video:

Resist the Pipeline video clip (a short, powerful overview of the event)

YouTube video clips:

- 6-minute video of the worship and arrests

- 3-minute video by Robert A. Jonas of the initial singing and prayers near the compressor station at Centre and Grove Streets in W. Roxbury

- 9-minute video by Robert A. Jonas of the religious leaders coming through the barrier, sitting down at the trench, praying, singing, and preaching

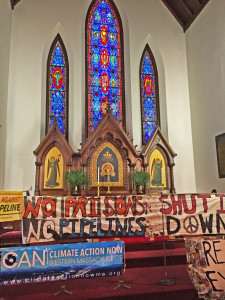

As a Christian climate activist, I found it stirring to realize that the rally was taking place on the eve of Palm Sunday, the day that Christians around the world step into Holy Week. Here were the stately altar and lectern arrayed in cloths of traditional red colors for tomorrow’s service, yet here, too, were banners draped across altar, pulpit and lectern, crying out in large letters: “No Prisons, No Pipeline. Shut It Down,” “Respect Existence, Expect Resistance,” and “Love Will Win.”

As a Christian climate activist, I found it stirring to realize that the rally was taking place on the eve of Palm Sunday, the day that Christians around the world step into Holy Week. Here were the stately altar and lectern arrayed in cloths of traditional red colors for tomorrow’s service, yet here, too, were banners draped across altar, pulpit and lectern, crying out in large letters: “No Prisons, No Pipeline. Shut It Down,” “Respect Existence, Expect Resistance,” and “Love Will Win.”

It is God who whispers that dream into our hearts, God who plants that longing in us like a seed that grows into a mighty oak, God who stirs us out of our complacency and sends us into action. It is God who gives us a heart to care, and strength to keep fighting the good fight. For it can be difficult to keep going, difficult to keep the faith in the face of sometimes brutal opposition and the sheer inertia of business as usual.

There is a wonderful scene in the movie

It is God who whispers that dream into our hearts, God who plants that longing in us like a seed that grows into a mighty oak, God who stirs us out of our complacency and sends us into action. It is God who gives us a heart to care, and strength to keep fighting the good fight. For it can be difficult to keep going, difficult to keep the faith in the face of sometimes brutal opposition and the sheer inertia of business as usual.

There is a wonderful scene in the movie