Sermon for the Sixth Sunday of Easter, May 1, 2016.

Delivered by the Rev. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas at

St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, Pittsfield, MA.

Acts 16:9-15

Psalm 67

Revelations 21:10, 22-22:5

John 5:1-9

Do you want to be made well?

I am blessed to worship with you this morning. Thank you, Cricket, for inviting me back to preach. The last time I was here, I served the Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts as your Missioner for Creation Care, but since then my job has expanded: now I also serve as Missioner for Creation Care for the United Church of Christ in Massachusetts. As far as I know, I’m the only person who holds the same job in both the Episcopal and UCC Churches. To me, this joint position, is an emblem of good things to come. As we awaken to the climate crisis, Christians of every denomination – in fact, people of every faith – have a precious opportunity – even in the midst of our wonderful and colorful diversity – to pull together and to speak with one voice about the urgent need to safeguard the world that God entrusted to our care.

Today’s Gospel text gives us a way to reflect on our call to protect and heal “this fragile Earth, our island home.” In a story from the Gospel of John, Jesus heals a paralyzed man whom he finds lying beside a pool. It is a quick little story – no more than nine sentences – so let’s pause to visualize the scene. The pool, called Beth-zatha, is located near one of the gates into Jerusalem. Years ago archaeologists actually located and excavated the pool.

[1] Apparently it was quite large and had four sides. Stairways were built in the corners of the pool, so that people could descend into the water, which may have been fed by springs that welled up at intervals. The bubbling waters were thought to have healing powers, and sick people – the blind, the lame, the paralyzed – came to the pool, believing that whenever the waters were stirred up, the first person to enter the pool would be cured of whatever sickness he or she had.

That’s the scene. Here’s the story. A man who has been ill for thirty-eight years is lying near the pool on his mat. The story doesn’t say how long he has been waiting to get into the water, but it does say that he has been there “a long time” (

John 5:6).

What do you imagine this man is going through, as he lies paralyzed for so long beside the pool? As I imagine it, he feels helpless. The waters that can heal him are close by, but out of reach. What can heal him is way over there, separated from him, at some distance away, and he can’t move toward it. He can’t reach it. He can’t get there. He is cut off from the source of healing, and he is utterly paralyzed. What’s more, he is cut off from the people around him, too, as he competes with the crowd to be the first to get into the pool when the waters bubble up. Who knows what he is feeling, but I would guess anxiety, frustration, desperation, even despair – all those painful, negative feelings that get stirred up when we feel helpless, vulnerable, and alone.

Now of course we can take the story literally, as a story about physical illness, but in John’s Gospel every story has an imaginative or symbolic dimension, too. When I imagine my way into this story and hear it in the context of climate change, all kinds of connections start playing in my mind. I start thinking about the ways the world’s web of life needs healing – about the alarming levels of carbon dioxide now pouring into the global atmosphere as coal, gas, and oil continue to be burned, about the oceans heating up and becoming more acidic, about the rising seas that could flood, disrupt, and even take down our country’s coastal cities within the lifetime of our children. I think about the new report saying that continued

burning of fossil fuels could cause great swaths of the Pacific Ocean to suffocate from lack of oxygen in only 15 years. I think about the

93% of coral reefs that just bleached in the Great Barrier Reef of Australia.

March 2016 was the hottest month ever recorded, which crushed the record set in February, which crushed the record set in January, which crushed the record set in December. A recent article in the Washington Post bears the title,

“Scientists Are Floored by What’s Happening in the Arctic Right Now.”

When we hear news like this about our ailing planet, it’s easy to stop listening. It’s too much to take in, so we shut down. We may feel paralyzed by anxiety or paralyzed by grief. Like that man beside the Beth-zatha pool, we may feel immobilized and overwhelmed. How can this dire news be true, and how can we possibly respond? Where can we turn for help and healing when our planet is on track to catapult into climate chaos caused by an ever-expanding economic system that runs on fossil fuels? People the world over can become so gripped by fear, anger, and despair that they feel unable to imagine, much less create, a better future, so they just carry on with business as usual. It’s as if we can fall under a spell and make what U.N. Secretary General Ban-ki Moon calls a “global suicide pact.”

So please turn with me again to our Gospel story. Jesus comes upon this scene of the blind, lame, and paralyzed beside the pool, and, the story tells us, “When Jesus

saw [the man] lying there and

knew that he had been there a long time, he said to him, ‘Do you want to be made well?’” (

John 5:6). That single sentence says a lot. The first step in this miracle of healing is that Jesus

saw the man and

knew him. John’s Gospel underscores again and again that when Jesus sees us and knows us, he sees and knows us through and through, more widely and deeply than we know ourselves. He looks deeply into us with eyes of love, with eyes that see the whole truth of who we are, and that perceive everything in us, everything about us, with loving-kindness and compassion. When we open ourselves to Jesus or to our Creator God in prayer, we open ourselves to the One “unto whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid” (Collect for Purity). In prayer, we turn toward the Holy Presence who searches for truth deep within and whose loving embrace encompasses everything we are, everything we feel.

That is the first step in today’s healing miracle: Jesus sees and knows. The second step in healing is his question, “Do you

want to be made well?” That is a surprising question. We might have expected Jesus to take one look at the situation, pick up the man without a word, carry him straight to the pool of healing water, and slide him in. Why waste time? Why bother asking such an obvious question? When someone is hungry, you offer food to eat; when someone is thirty, you offer drink. Why mess around asking questions?

But Jesus’ question reveals something important. The God we meet in Jesus does not force or push, even when it comes to healing. The God we meet in Jesus is deeply respectful of our freedom and gives us space in which to choose. It seems that in order for real healing to take place and new life to spring forth, God’s desire to heal us must meet our own desire to be healed. Do you want to be made well? It is not just a rhetorical question with a pro forma answer. The question invites the man paralyzed beside the pool to explore his desires and to clarify what he truly wants.

Regarding the climate crisis, do I really want to be made well? Well, yes and no. Part of me prefers to stay blind, to close my eyes, duck my head, and turn my attention to more manageable things. Part of me prefers to come up with lame solutions: OK, I’ll change the light bulbs, but that’s it, I’ve done my part. Part of me feels paralyzed: I’m no expert; I’m too small to make a difference; surely someone else will take charge and figure this out.

How does the man by the pool reply to Jesus? “‘Sir,’ [the man says,] ‘I have no one to put me into the pool when the water is stirred up; and while I am making my way, someone else steps down ahead of me’” (

John 5:7). Jesus’ response is powerful and short: “‘Stand up, take your mat and walk.’ And at once the man was made well, and he took up his mat and began to walk” (

John 5:8-9).

What just happened? How did the healing miracle take place? I can’t explain it. But as I imagine it, as Jesus gazed on the man with those piercing, loving eyes that saw and knew and loved him through and through, and when Jesus asked him the probing question, “Do you want to be made well?,” in a flash of insight the man could admit his own halfheartedness and mixed motives and the ways he’d been holding back. I imagine that he felt his deep-down desire to be whole and free, his longing to love and be loved, his longing to draw close to God and to serve God “with gladness and singleness of heart.”

So I imagine him claiming his deepest desire and turning to Jesus to say, “Yes, I want be fully alive. I want to fall in love with life, to give myself in love to each moment without holding anything back. I want God’s healing power to flow through me, so that I heal others and so that I, too, am healed.” The Gospel does not record that conversation, but I imagine it happening non-verbally by glance and gesture, as the sick man looked up at Jesus and said, without words, “Yes, I want to be made well.”

“Stand up,” Jesus said, “and walk.”

And he did.

And so can we.

Amazing things happen when we join our deep desire for healing with God’s deep desire to heal. When I look around, I see a planet in peril, but – thanks be to God! – I also see people shaking off their paralysis, reaching deep into their souls, and accessing their deep, God-given desire to love and serve life. I see people standing up to join the struggle to maintain a habitable planet and to create a just and sustainable future. I see a wave of religious protest and activism rising up around the world, as people refuse to settle for a killing status quo and declare that climate change is a spiritual and moral issue that must be tackled boldly and without delay.

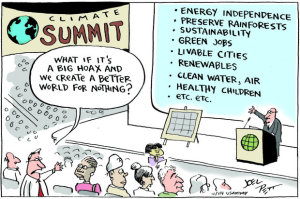

Just think of all the signs we see of a growing movement that is pushing for a new social order. We see people blocking the path of new fracked gas pipelines and being arrested for civil disobedience as they read aloud from Pope Francis’ encyclical. We see people lobbying for a fair price on carbon, so that we can build a clean green economy that provides decent jobs and improves public health. We see our own Episcopal Church deciding to divest from fossil fuels, since it makes no financial or moral sense to invest in companies that are ruining the planet. We see new coalitions being formed and new alliances being forged, as people realize that the environmental crisis is closely connected with the social crises of poverty, income inequality, and racial injustice.

Right here in Massachusetts we have a strong grassroots climate action network,

350Mass for a Better Future, which has a node right here in the Berkshires. I’ve left a clipboard at the back of the church, and if you sign up for the weekly newsletter or attend a node meeting, you’ll connect with a vibrant local effort. I’m also part of a new group,

Massachusetts Interfaith Coalition for Climate Action, or “MAICCA” for short, which is bringing together people of different religious traditions to advocate on Beacon Hill for legislation that supports climate justice. I hope you’ll sign up for MAICCA’s newsletter, too, for we are fighting to keep fossil fuels in the ground and to accelerate a transition to clean, safe, renewable sources of energy, such as sun and wind, that are accessible to all communities, including those that are low-income or historically underserved. As climate activist Bill McKibben points out, “The fight for a just world is the same as the fight for a livable one.”

The Church was made for a time like this – a time when God calls human beings to know that we belong to one Earth, that we form one human family, and that God entrusted the Earth and all its residents to our care.

One last word about our Gospel story: notice that the man didn’t need to be immersed in the pool of Beth-zatha in order to be healed. In Jesus’ presence, the man discovered that the healing spring was not outside him – it was inside him, just as it is inside us. As Jesus told the woman at the well (

John 4:1-26), Jesus gives us water that becomes in us a “spring of water gushing up to eternal life” (

John 4:14). Even in troubled and scary times, we have everything we need. The healing pool is within us; the spring of healing is already bubbling up; and Jesus will nourish us with his presence in the bread and wine of the Eucharist. In the strength of that bread and wine and through the power of the Spirit, we can be healed from paralysis and become healers and justice-makers in a world that is crying out for our care.

1.

The Anchor Bible: The Gospel According to John (I-XII), introduction, translation, and notes by Raymond E. Brown, S.S., Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1966, pp. 206-207.

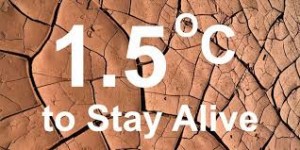

“1.5 to stay alive” – that is the cry of every God-inspired prophet who stands like Elijah beside the vulnerable Naboths of this world.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with the low-income community of Baltimore that is fighting for the right to clean air.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with Pacific Islanders forced to leave their homeland because rising waves are washing away their buildings and contaminating their water supply.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with indigenous peoples in the Arctic whose cultures are disintegrating as the ice melts.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with frightened pregnant women in the global South and the Southern U.S. who know that the Zika virus, which spreads in a warm, humid climate, could irreparably harm their unborn child.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with every person and every community that wants to live in a just and peaceful world with recognizable seasons and moderate, predictable rains, in a world with enough clean, fresh water for all and an ocean teeming with life.

And we say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand against the political and corporate powers that view the Earth as nothing more than a source of profit and who exploit the Earth and other people as if it’s every man for himself and the Devil take the hindmost.

Thanks to Bob Parati, we have a sign that proclaims, “1.5 to stay alive.” After the service, I invite anyone who wishes, to join me outside so that we can take a group photo.

I invite you to do some other things, too. If you haven’t done so already, I invite you to join

“1.5 to stay alive” – that is the cry of every God-inspired prophet who stands like Elijah beside the vulnerable Naboths of this world.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with the low-income community of Baltimore that is fighting for the right to clean air.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with Pacific Islanders forced to leave their homeland because rising waves are washing away their buildings and contaminating their water supply.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with indigenous peoples in the Arctic whose cultures are disintegrating as the ice melts.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with frightened pregnant women in the global South and the Southern U.S. who know that the Zika virus, which spreads in a warm, humid climate, could irreparably harm their unborn child.

We say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand with every person and every community that wants to live in a just and peaceful world with recognizable seasons and moderate, predictable rains, in a world with enough clean, fresh water for all and an ocean teeming with life.

And we say “1.5 to stay alive” to stand against the political and corporate powers that view the Earth as nothing more than a source of profit and who exploit the Earth and other people as if it’s every man for himself and the Devil take the hindmost.

Thanks to Bob Parati, we have a sign that proclaims, “1.5 to stay alive.” After the service, I invite anyone who wishes, to join me outside so that we can take a group photo.

I invite you to do some other things, too. If you haven’t done so already, I invite you to join