Here is a story from this week’s trip to Arizona, where I attended a retreat led by James Finley, preached in Tucson, and hiked in the desert.

© Robert A. Jonas

What value does a mountain have? In 1949 the Portland Cement Company built the first cement plant in Arizona, 20 miles northwest of Tucson. They built the plant about four miles from Twin Peaks, a pair of small mountains that rose side by side from the desert floor, and they set to work extracting limestone from one of them. The business of digging into the mountain proceeded swiftly and efficiently, especially after a covered conveyer belt nearly four miles long was built in 1972: it could transport up to 800 tons of limestone and shale from the quarry to the plant every hour. By then the plant was operating three kilns, each one longer than a football field, and supplying the growing cities of Tucson and south Phoenix with 3 million barrels of cement every year.

Today a traveler visiting Twin Peaks will look in vain for the pair of mountains. One of them has vanished. Not just the mountaintop has been removed – the whole mountain is gone. Even its roots have been excavated. All that remains is an empty pit, an open wound. (For an aerial view, click here.)

There are several ways to tell this story. Is it a tale of humanity’s cleverness and ingenuity? Of how adept we are at exploiting natural resources to satisfy our comforts and needs? Thanks to limestone and the other industrial minerals that are mined in Arizona, consumers enjoy products that we use every day, from cement to brick, from tile, glass, and asphalt to trains, planes, and cars. You might call this is a success story: because of the cement company, countless jobs have been created, families fed, and buildings constructed.

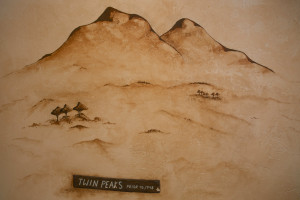

Or is it a cautionary tale? I gaze across the desert, looking at the empty space where a mountain once stood, and mourn the loss. Twin Peaks exists now only in name and memory. A drawing of the two peaks as they looked before 1948 is sketched on the wall of a nearby ranch. Seeing what remains of them now, it is hard not to think of a radical mastectomy.

© Robert A. Jonas

Meanwhile, the economic engine keeps pounding. Every year in Tucson, more acres of desert are scraped bare, more subdivisions are erected, and more houses clamber up the mountain slopes. Year by year more saguaro are cut down, more animals are displaced, and more groundwater is pumped out to farm the desert and to feed the sewer systems, fountains, and swimming pools that accompany the construction that cement makes possible. The Sonoran Desert is large, and in theory there is still plenty of space for human habitation to expand. But what seems like the possibility of endless growth, a march of Manifest Destiny into the desert, is just a mirage. A few days ago officials in Arizona made the startling announcement that in as few as five years, Tucson and Phoenix could face cutbacks in their deliveries of water from the Colorado River. The metropolis that swallowed up a small mountain is now sucking its water reserves dry.

Is this a parable of a civilization in peril? Of a society that can’t stop itself from gobbling up the Earth upon which all existence – including its own – depends? What value does a mountain have? Does it matter when a mountain is lost?

I walk into the desert to pray. To my right, I glimpse the lone remnant of Twin Peaks, looking odd and forlorn, an amputee. Straight ahead is a grand ridge of mountains that rises near the border of Saguaro National Park. Eagerly I study the ridge’s contours and jagged cliffs. I watch shadows play across its flanks as the sun rises, and I sense its vast and solid bulk. Who are you, Mountain? What is it like to be you? Who am I to you? Who are you to me?

© Robert A. Jonas

My interchange with Mountain is carried out in silence by intuition and imagination. I give Mountain my steady attention, observing everything I can. I notice that it is producing nothing, achieving nothing, planning nothing, regretting nothing. By human standards it has no purpose at all; it simply is. I sense its inscrutable existence beyond the grasp of human thought. I sense its silence, and my mind grows quiet. I sense its wildness, and my spirit stirs. I sense its freedom, and my spirit takes flight. In the company of Mountain, I am restored to myself and filled with joy.

It is strange that an impenetrable mountain can become a doorway to the Holy, strange that from arid rock we can drink from a river of life. I wonder if human beings discover our true identity only in relation to something that is greater than ourselves.

What value does a mountain have? From the mountains of Sinai and Zion to the Mount of Transfiguration, Mount Athos, and beyond, we know that mountains are a place of encounter with the divine. Their value is beyond human calculation. It’s no wonder that groups such as Christians for the Mountains are active in trying to stop mountaintop removal in West Virginia, for even more is at stake than protecting clean air, clean water, decent jobs, and public health. What’s ultimately at stake is protecting our relationship with God.

Tucson has lost a small mountain, but, God willing, those who live and work in Tucson, and those who visit, will learn something essential from the mighty mountains that remain. I hope that we humans never lose our capacity to cherish mountains as more than scenic backdrop to a swimming pool and more than deposits of limestone or coal. I pray that we humans rediscover the intrinsic value of wilderness and perceive its holiness. Sometimes such places remind us, as nothing else can, that we belong to a sacred mystery whose wild, more-than-human presence gives value and meaning to our lives.

I am co-leading two upcoming retreats on Christianity and ecology:

• “Pilgrimage for Earth: From Loss to Hope” on Saturday, June 28, 2014, at Mission Farm, Killington, VT; and

• “The Heart of Creation: Cultivating Hope in a Wounded World” on the weekend of July 11-13, 2014, at Adelynrood Retreat & Conference Center, Byfield, MA.

See the Events page on this Website for more information.