This article by Margaret Bullitt-Jonas was published in Anglican Theological Review (Spring, 2021, Vol. 103, 2), pp. 208–219.

I have preached countless sermons in countless settings about the urgent Gospel call to care for God’s Creation. Nevertheless, when I step into a literal or virtual pulpit to preach about the climate crisis, I still feel a flash of fear: This will be a disaster.

Preaching on any topic is inherently challenging. As Ruthanna B. Hooke explains in Transforming Preaching, there are many good reasons that newcomers and experienced preachers alike find it frightening to preach.1 Fear, she argues, is an intrinsic and even necessary aspect of preaching God’s Word: preaching can only be authentic when we truly open ourselves to the presence of the living God and publicly put our life and faith on the line. Barbara Brown Taylor compares watching the preacher climb into the pulpit to watching a tightrope walker climb onto a platform as the drum rolls.2 Preaching of any kind requires risky self-exposure and walking in faith. Before they embark, preachers and tightrope walkers must pray: Even there your hand will lead me and your right hand hold me fast (Ps. 139:9).

However, preaching about the climate crisis may evoke particular anxiety. Although climate change is called the great moral challenge of our time, many preachers avoid preaching about it – often because of fear. Maybe we fear being ill-informed (I don’t know enough science). Maybe we fear provoking division in the congregation (Climate change is too political). Maybe we fear stressing out our listeners (Daily life is hard enough; why add to their worries?) or maybe we fear they won’t be able to handle the bad news (If I do mention climate change, I’d better tone it down and underplay the dire science). Maybe we fear that climate preaching is not pastoral (People come to church for solace, not to get depressed). Besides, we may tell ourselves, preaching about climate change should be someone else’s responsibility (Climate change isn’t really “my” issue). A preacher’s fears may cut close to home (I could lose pledges; I could even lose my job). Climate preaching may also require a painful reckoning with oneself that the preacher would prefer to avoid. Such a reckoning may be spiritual and theological (How do I preach resurrection when the web of life is unraveling before our eyes?) or it may be personal and moral as we face our own complicity. As one suburban preacher confessed to me years ago, “How can I preach about climate change when I drive an SUV?”

No wonder so many preachers delay addressing the climate crisis – most of us weren’t trained for this, we don’t want to stir up trouble, and we face an array of fears. As a result, many of us kick the can down the road, perhaps waiting for the lectionary to provide the “perfect” text, for a guest preacher to introduce the subject, or for a special (and thankfully rare) occasion, such as Earth Sunday or St. Francis Day.

Preachers who are hanging back from speaking about the climate emergency and those who have been preaching about it for years owe a debt of gratitude to Greta Thunberg, designated by TIME magazine as its 2019 Person of the Year. Thunberg is the Swedish teenager with the round face and straight blonde hair who delivered a fierce message to the U.S. Congress, the United Nations, the World Economic Forum, and all the adults who failed to take action: “Our house is on fire… We have to stop our emissions of greenhouse gas emissions. Either we do that or we don’t… Either we prevent 1.5C of warming or we don’t… Either we choose to go on as a civilization or we don’t… We all have a choice. We can create transformational action that will safeguard the living conditions for future generations. Or we can continue with our business as usual and fail. That is up to you and me.”3

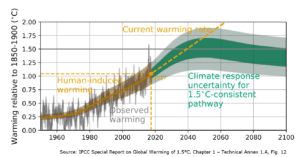

Preach it, Greta! Although Thunberg is not addressing the religious faith of her audience, her fiery words and presence convey the message of a prophetic preacher: humanity stands at a crossroads and we have a vital choice to make, a choice of life or death, blessing or curse (Dt. 30:19). Science shows that we are at the brink of catastrophe: the only way to avert climate chaos and to protect life as it has evolved on Earth is to carry out a top-to-bottom transformation of society at a speed and scope that are historically unprecedented.4 We need to keep fossil fuels in the ground, where they belong. We need to make a decisive change of course toward clean, renewable sources of energy. We need to protect forests and topsoil, rivers and oceans, pollinators and the other living creatures with whom we share this planet, to say nothing of the eco-systems upon which all life depends. And we must do this quickly, equitably, and despite the opposition of entrenched political and corporate powers that are determined to keep drilling, burning, mining, extracting, plundering and profiting for as long as they can – even though business as usual is wrecking the planet. Thunberg’s moral call to action galvanized millions of people around the world and inspired the global climate strike on September 20, 2019, which is so far the largest climate demonstration in human history.

Hearing a strong sermon can dissolve fear, awaken moral responsibility, and mobilize action. I know this from direct experience – I was preached into jail by Bishop Steven Charleston. Back in 2001, while listening to him preach resurrection at an Easter Vigil service, I heard God’s call: I realized that in order to bear witness to the Risen Christ, I needed to gather up my courage and carry out my first extended act of civil disobedience. A few weeks later I joined a new interfaith group, Religious Witness for the Earth, and headed to Washington, D.C., to protest the Administration’s intention to drill for more oil in the Arctic.

Here’s what happened: about a hundred of us from different faith traditions marched down Independence Avenue in our diverse religious vestments, carrying banners and singing. When we reached the Department of Energy, which was surrounded by police, we held a brief worship service. After singing “Amazing Grace,” the twenty-two of us who had decided to risk arrest joined hands and walked slowly to the doors of the Department of Energy.

As I later wrote, describing the moments before our arrest:5

We stand or kneel in prayer, our backs to the building. The pavement under my knees is hard. At home, I often sit on a meditation cushion to pray. Today there is no cushion, just the weight of my body against stone. I lift up my hands. I’m dressed for the Eucharist. I might as well hold out my arms as I do at the Eucharist….

One by one we pray aloud, words thrown into space, words hurled against stone. Is this whole thing ridiculous? …

But then came the revelation:

Suddenly I realize that behind the tension, behind the fear and self-consciousness, something else is welling up. I am jubilant.

“Lift up your hearts,” I might as well be saying to the people before me, beaming as broadly as I do at the Eucharist.

“We lift them to the Lord,” would come the response.

How did I miss it? After years of going to church, after years of celebrating the Eucharist, only now, as I kneel on pavement and face a phalanx of cops, do I understand so clearly that praising God can be an act of political resistance. That worship is an act of human liberation. The twenty-two of us come from different faith traditions, but each of us is rooted in a reality that transcends the rules and structures of this world. Tap into that transcendent truth, let the divine longing for a community of justice and mercy become your own deepest longing, and who knows what energy for life will be released?

I feel as defiant as a maple seedling that pushes up through asphalt. It is God I love, and God’s green earth. I want to bear witness to that love even in the face of hatred or indifference, even if the cost is great.

So what if our numbers are small? So what if, in the eyes of the police, in the eyes of the world, we have no power? I’m beginning to sense the power that is ours to wield, the power of self-offering. We may have nothing else, but we do have this, the power to say, “This is where I stand. This is what I love. Here is something for which I’m willing to put my body on the line.”

I never knew that stepping beyond the borders of what I find comfortable could make me so happy. That shifting from self-preservation to self-offering could awaken so much joy.

Is this what Jesus meant when he promised that the poor in spirit would receive the kingdom of heaven and that those who hunger and thirst for righteousness would be filled (Mt. 5:3, 6)? I am hardly the first climate-justice or social-justice activist to discover that her understanding of the Gospel deepens immeasurably as she bears public (and risky) witness to her faith. As Robert Raines (former director of Kirkridge Retreat and Study Center in Bangor, PA) put it years ago, “The Gospel is just so much wind until we raise our lives against it like a sail.”

Strong sermons on climate change create the conditions for that kind of spiritual awakening: preacher and listeners alike are invited to take hold of their deepest convictions as they ask themselves: What do I truly value? What is love calling me to do? What is my moral responsibility to future generations? Am I willing to settle for a way of life that is destroying the web of life that God entrusted to our care? Am I ready to imagine a better future and to join with other people who are fighting for a just and habitable world? These are difficult and essential questions that all of us must face, individually and together. Jesus wept over Jerusalem because the city “did not recognize the time of your visitation from God” (Lk. 19:44). Are we willing to recognize that we, too, live in such a time? This is a holy moment, a moment of truth, a moment of reckoning. Our calling as preachers is to step through whatever fears hold us back and to take up our pastoral and prophetic vocation to preach Gospel hope in a time of unprecedented human emergency.6

Are there any “best practices” for climate preaching? The Episcopal Church, in conjunction with ecoAmerica and Blessed Tomorrow, has produced a helpful manual. “Let’s Talk Faith and Climate: Communication Guidance for Faith Leaders,”7 released in 2016, explains why our faith calls us to lead on climate, provides key talking points, and gives examples of “successful messaging.” The chapter, “Prophetic Preaching,” in Jim Antal’s must-read book, Climate Church, Climate World: How People of Faith Must Work for Change,8 is likewise worth careful study, suggesting guidelines and what he calls “theological cornerstones” for climate preaching. Another timely book is Leah D. Schade’s Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit,9 which explores how to proclaim justice for God’s Creation in the face of climate disruption.

Based on my reading and lived experience, I hold several things in mind when I preach about climate change.

• Frame the climate crisis in terms of Christian theology. In a highly partisan, divided society, simply uttering the phrase “climate change” can make an audience twitch: Uh-oh. Here comes a sermon about politics. Our task as preachers is to re-frame the conventional narrative that climate change is only a scientific, political, or economic issue, and instead to place it front and center as a subject of urgent spiritual and moral concern for every Christian. Every climate preacher will need to locate the bedrock of Scripture, theology, and religious experience that establishes their worldview and values.10

I often make these points:

• God loved the world into being, pronounced it “very good” (Gen. 1:31), and entrusts it to our care. I sometimes reference the origin story in Genesis, though I critique the concept of “dominion” (Gen. 1:26) when it is interpreted as divine permission for humanity to dominate and abuse the world. In my view, “dominion” does not refer to what Alcoholics Anonymous would call “self-will run riot”; rather, it means loving the world as God loves it. The second charge, to “till and keep” (Gen. 2:15) the garden, expresses more clearly our primary vocation to be a blessing on God’s Creation.

• The Earth does not belong to us, but to God (Ps. 24:1). The concept of “stewardship” reminds us that we are here to serve the Lord of life, not ourselves, and that our task is to safeguard Earth rather than to ransack and plunder. Still, the word “steward” can sound wimpy to me, as if our responsibility is limited to recycling the occasional can. Let’s find a more robust term to refer to the “children of God” for whom Creation is so eagerly longing (Rom. 8:19-22). Maybe we need to be “spiritual warriors” engaged in “sacred activism.”

• Jesus lived in close relationship with the natural world. In the Gospels we find him walking along the seashore and up mountains, taking boats out on the lake, and spending weeks alone in the wilderness in prayer. His parables and stories are full of natural images: sheep and seeds, sparrows and lilies, water and fire, weeds, vines, and rocks. What would it be like to reclaim the kind of intimacy with the natural world that Jesus knew – to know, as he did, that “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows [God’s] handiwork” (Ps. 19:1)? In my sermons, I often try to restore a sense of reverence for God’s Creation, to dismantle the fossil-fuel mindset that the natural world is nothing more than inert material, an object for us to exploit. The Earth, in fact, is a primary locus for our encounter with God. Such is the testimony of generations of Christian mystics and theologians, beginning with St. Paul (Romans 1:20). Like poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, we affirm: “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.” Destroying Earth is therefore a desecration, a sin against the Creator.

• The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ affected and redeemed not only human beings but also the whole of Creation.11 Christ is the Word through whom all things were made (Jn. 1:3). In him, “all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross” (Col. 1:19-20; c.f. also Eph. 1:10, 2 Cor. 5:19). Creation is thus made new (Rev. 21:5). As we relinquish a narrowly anthropocentric understanding of the Gospel, we realize that all of Creation participates in the Paschal mystery. Our search to create a more just and habitable world and to live more gently on Earth is how we share in what Archbishop Desmond Tutu calls the “supreme work”12 of Jesus Christ, who reconciles us to God, to one another, and to God’s whole Creation.

• We are called to love our neighbors. Are we loving our neighbors when we drown them, starve them, and force them to uproot themselves from their homelands? The rising seas, droughts, and extreme storms amplified by climate change are already harming innumerable neighbors, especially in the global South. Our “neighbors” likewise include future generations who depend on us to leave them a habitable world, and also the other-than-human creatures with whom we share this planet. God forged an “everlasting covenant” not only with human beings but also with “every living creature” (Gen. 9:8-17) – they, too, are the “neighbors” we are summoned to love.

• We are called to bear witness to a love that transcends death. In our baptism, we are immersed in the waters of death. We die in Christ and with Christ. And then we rise with Christ: from now on, our death is done with. It is behind us. We have died with Christ and are now alive in Christ – and to whatever extent we can take this in, we are set free from anguish and anxiety, set free to love without grasping or possessiveness or holding back. In the early centuries of the Church, Christians were called “those who have no fear of death.”13 That inner fearlessness, rooted in the love of God, empowered the early Christians to resist the unjust powers-that-be: early on they were charged with “turning the world upside down” (Acts 17:6) and “acting contrary to the decrees of the emperor (Acts 17:7). Their inner liberation gave them courage to resist the forces of death and destruction, and to obey God rather than any human authority (Acts 5:29).

• Respect the lectionary, but don’t make it an idol. If you knew your house was on fire, would you wait for the “perfect” moment before calling for help to douse the flames? Not a chance. Once we know that climate change is an emergency, we will quite naturally seize every tool at hand. This Sunday’s lectionary readings could be the perfect springboard for a sermon on climate change. If we can’t make a direct connection, we can ditch the lectionary and preach about climate change in relation to the liturgical season, the Eucharist, or themes such as incarnation, justice, compassion, sin and forgiveness, and Christian witness and responsibility. I enjoy The Green Bible, which highlights in green font the biblical texts that the book’s editors consider most relevant to Earth-care. However, it seems to me that thousands of other biblical passages could just as well have been marked in green, for I read the whole Bible as a love-song between God and God’s Creation, as a living text that calls us to bear witness to a triune God who loved the world into being, who suffers with us and for us, and who empowers us to live together in right relationship with each other and the land.

My Website, RevivingCreation.org, includes about one hundred lectionary-based sermons about climate change and Creation care. SustainablePreaching.org is an ecumenical online resource that offers lectionary-based sermons on Creation care and a tool for searching out particular Bible passages.

• Share some science, but don’t worry that you need to be a scientist. As climate preachers we need to know and share the basics: climate change is real, it’s largely caused by human activity, it’s gotten worse in recent decades, and it will have disastrous effects unless humanity changes course fast. Basic information is available from many sources, such as NASA or reputable environmental groups like Natural Resources Defense Council.14 For up-to-date climate news, I subscribe to the weekly newsletter of InsideClimateNews.org15 and to daily news from Climate Nexus.16

In preaching I usually keep the science message short, brisk, and sober. To summarize the big-picture effects of a changing climate, I often quote a couple of sentences by Bill McKibben: “We’ve changed the planet, changed it in large and fundamental ways… Our old familiar globe is suddenly melting, drying, acidifying, flooding, and burning in ways that no human has ever seen.”17 Then I cite specific examples that might especially resonate with the local congregation (in California: drought, wildfire, and mudslides; on Cape Cod: rising and acidifying seas, and threats to groundwater and fishing).18 One reason that parishioners may be relieved to hear climate change discussed in church is that increasing numbers of Americans understand that climate change is already affecting their communities.19

• Find an entry point and connect the dots. What are the particular concerns of your congregation? Begin there and show how they link to climate change. The novel coronavirus, for example, teaches lessons that relate to climate change: science matters; how we treat the natural world affects our wellbeing; the sooner we mobilize for action, the less suffering will take place; we have the ability to make drastic changes quickly; all of us are vulnerable to crisis, though unequally.20 Climate change increases the likelihood of pandemics, because flooding, droughts, and weather extremes force agriculture into new areas. Converting more natural habitat into crop land accelerates the loss of biodiversity and increases the incidence of zoonotic diseases, those spread between wild animals and humans.21

Climate change also exacerbates economic and racial injustice. Low-income communities and communities of color are the ones hit first and hardest by climate change, the ones least able to prepare or recover, and the ones least likely to have a seat at the table where policy decisions are made.22 Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, recently reported on the risk of “climate apartheid,” where the rich pay to escape the increasing heat and hunger caused by the climate crisis and the rest of the world suffers.23 So-called “climate gentrification” – where wealthy people seek refuge from the effects of climate change and move into once “undesirable” neighborhoods – forces out low-income and minority residents.24 Mary Annaïse Heglar, a climate justice writer who is also Black, details the ways in which Black people suffer disproportionately as temperatures rise, and she issues a clarion call, “It’s time to stop #AllLivesMattering the climate crisis.”25

Climate change is not one of 26 different causes that we care about – it is a cause that affects everything we cherish. The Pentagon has long called climate change a “threat multiplier,” which means that it amplifies existing problems. If we care about pandemics and public health, we care about climate. If we care about racism and human rights, we care about climate. If we care about poverty, homelessness, and hunger, we care about climate. If we care about immigration and refugees, we care about climate. (How many people worldwide will be forced to move by 2050 because of climate change? Estimates range between 25 million and one billion.26). If we care about violence against women and girls, we care about climate: climate change aggravates gender-based violence.27 If we care about preventing war, we care about climate: climate change increases the risk of conflicts over increasingly scarce resources, such as water and arable land.28

In short, if we care about loving God and neighbor, we care about climate. The climate does not belong to a special-interest group. If we like to breathe, if we like to eat, if we want to leave our children a world they can live in, we care about climate. That is why it is so important to build an intersectional movement that pulls people out of their isolated silos of concern and pushes for comprehensive solutions: the groups protecting wilderness areas, farmlands, and wildlife habitat need to support and learn from the groups addressing racism, poverty, and asthma in the inner city. As Pope Francis wrote in his encyclical, Laudato Si, we don’t face two crises, one social and one environmental, but rather “one complex crisis which is both social and environmental. Strategies for a solution require an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature.”29

• Infuse your sermons with the empowering love of God. The more that people know about (and experience) the social and ecological breakdown going on worldwide, the more likely they are to feel paralyzed, panicked, or depressed. Despair holds many people in an icy grip. That is why a message of urgency needs to be accompanied by a message of empowerment and strength: God is with us.

I am deeply interested in the spiritual perspectives and practices that can sustain climate activism, even in the face of dire news about our planet’s health and the possibility that civilization will collapse. In order to be healers and justice-makers, in order to bear witness to the Christ who bursts out of the tomb and proclaims that life and not death will have the last word, we need to be emotionally and spiritually resilient. In this time of unprecedented challenge, where will we find the energy and hope to keep working toward solutions without giving up? To help answer that question, my colleague Leah Schade and I collected and edited an anthology of twenty-one essays from diverse faith traditions, Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis.30

Whenever I preach, I try to evoke the presence of a God who loves us beyond measure, a God who heals and redeems, liberates and forgives. I preach about a God who honors and shares our climate grief, a God who weeps with us; understands our outrage, fear, and sorrow as the living world around us is destroyed; and, in the words of Peter Sawtell, calls us “to active resistance, not to quiet acceptance.”31 I preach about a God who knows our guilt and complicity in that destruction and who gives us power to amend our lives. I preach about a God who longs to create a Beloved Community32 that includes all beings, not just human beings. I preach about a God who releases us from the tyranny of death and who gives us strength to bear witness to a love that nothing can destroy.

• Build hope by taking action. In almost every climate sermon, I include suggestions for faithful action33 such as cutting back sharply on our use of fossil fuels, moving toward a plant-based diet, going solar, and planting trees and community gardens. Individual actions to reduce our household carbon footprint are essential to our moral integrity and help to propel social change. Yet the scope and speed of the climate crisis also require engagement in collective action for social transformation. We need to use our voices and our votes and make it politically possible to do what is scientifically necessary. We can support the growing movement to hold Big Polluters like Exxon and Koch Industries financially and legally liable for the damages they knowingly caused (and continue to cause). We can lobby for policies that support renewable energy, clean green jobs, and a just transition that addresses the needs of poor and low-wealth communities and communities of color. If we have financial investments, we can divest from fossil fuels. If we’re college graduates, we can push our alma mater to divest. We can support 350.org, Sunrise Movement, Extinction Rebellion and other grassroots efforts to turn the tide. Maybe we can join the growing numbers of resolute and faith-filled people who carry out peaceful civil disobedience and put our bodies on the line.

If the voice of one young woman – Greta Thunberg – can rivet the attention of the world, what would happen if preachers everywhere unleashed their own passion for God’s Creation? What would happen if preachers across the Episcopal Church and in every religious tradition began to speak boldly and frequently about our moral obligation to create a more just and habitable world? Just as ecosystems have so-called tipping points – a critical point when they suddenly undergo rapid and irreversible change – so, too, human communities can experience a tipping point after which society changes swiftly in dramatic ways. Is such a thing possible in terms of rapidly decarbonizing a society? According to a recent article in the journal Anthropocene, an analysis published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences “suggests the answer is yes. In it, an international team of researchers argues that seemingly small ‘tipping points’ can trigger large, rapid changes in societies.”34 The team identified six relatively small, positive interventions that could help bring about systemic global change quickly, especially if they were carried out simultaneously. One of them sounds as if it were crafted with preachers in mind: “Activists and opinion leaders could emphasize the moral implications of fossil fuels – that is, the idea that burning fossil fuels in ways incompatible with the Paris climate targets is immoral. This has the potential to shift societal norms and, consequently, widespread patterns of behavior.”35

When we deliver strong climate sermons and put our trust in the power of the Holy Spirit, I wonder if we are like the boy in the story of Jesus feeding the five thousand (Jn. 6:1-14): we put our words in Jesus’ hands and through his grace and power, maybe our offering will become the catalyst that enables a crowd to be fed. Maybe our words, like those of Ezekiel, will be infused with Spirit-power to enliven dead, dry bones and breathe life into a multitude (Ez. 37:1-14). Maybe that homily – that word of challenge, consolation, or encouragement – will contribute to the tipping point that releases a rapid societal transformation.

What do preachers do in a time of unprecedented emergency? Right before we preach our next sermon about climate change, we acknowledge our fear (This will be a disaster.) We entrust ourselves to God (Even there your hand will lead me and your right hand hold me fast). Then we take a breath, open our mouths, and speak.

* Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, PhD, serves as Missioner for Creation Care (Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts and Southern New England Conference, United Church of Christ) and Creation Care Advisor (Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts). An Episcopal priest, author, retreat leader, and climate activist, she has been a lead organizer of many Christian and interfaith events about care for Earth, and she leads spiritual retreats in the United States and Canada on spiritual resilience and resistance in the midst of a climate emergency. Her latest book, Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (2019), co-edited with Leah Schade, is an anthology of essays from religious environmental activists on finding the spiritual wisdom for facing the difficult days ahead. Her website, RevivingCreation.org, includes sermons, blog posts, articles, and newsletters.

Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, “Preaching when life depends on it: climate crisis and Gospel hope,” Anglican Theological Review (Vol. 103, 2), pp. 208–219. Copyright © 2021 Margaret Bullitt-Jonas. DOI: 10.1177/00033286211007431.

Link to the article on ATR: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00033286211007431

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Ruthanna B. Hooke, “Why Is It Frightening to Preach?” in Transforming Preaching (New York: Church Publishing, 2010), 1-21.

2. Barbara Brown Taylor, The Preaching Life (Cambridge, MA: Cowley Publications, 1993), 76, quoted by Hooke, Transforming Preaching, 3-4.

3. Greta Thunberg, “’Our house is on fire’: Greta Thunberg, 16, urges leaders to act on climate,” The Guardian, January 25, 2019.

4. Chris Mooney and Brady Dennis, “The world has just over a decade to get climate change under control, U.N. scientists say,” Washington Post, October 7, 2018.

5. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, “When Heaven Happens,” in Heaven, ed. Roger Ferlo (New York: Church Publishing, Inc., 2007), 79, 80-81. For information and support regarding civil disobedience, I suggest Climate Disobedience Center and Clergy Climate Action.

6. I helped to draft the 2019 statement by National Religious Coalition on Creation Care, “Religious Declaration of Unprecedented Human Emergency.” As the statement makes clear, this is not only a “human” emergency but one that affects all life on Earth. In March 2021, the bishops of the Episcopal dioceses of Massachusetts and Western Massachusetts declared a climate emergency.

7. “Let’s Talk Faith and Climate: Communication Guidance for Faith Leaders.” Other Episcopal resources for climate communication and for building momentum on climate solutions in your congregation and community are available at https://www.episcopalchurch.org/ministries/creation-care/.

8. Jim Antal, “Prophetic Preaching,” Climate Church, Climate World (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), 121-135.

9. Leah D. Schade, Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (St. Louis, MO: Chalice Press, 2015).

10. For a helpful theological and devotional resource, view “A Catechism of Creation: An Episcopal Understanding.”

11. For a brilliant sermon that evokes how Creation shared in Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, read Leah D. Schade’s “A Resurrection Sermon for an Earth-Kin Congregation,” which was preached outdoors and is included in Creation-Crisis Preaching, 85-89.

12. Archbishop Desmond Tutu, “Foreword,” The Green Bible (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers (HarperOne), 2008, I-14.

13. Olivier Clement, The Roots of Christian Mysticism (London: New City, 1993), p. 107.

14. https://climate.nasa.gov/resources/global-warming-vs-climate-change/,

https://www.nrdc.org/stories/global-climate-change-what-you-need-know/.

15. https://insideclimatenews.org/. “A Pulitzer Prize-winning, non-profit, non-partisan news organization dedicated to covering climate change, energy and the environment.”

16. To sign up, send an email to: info@climatenexus.org.

17. Bill McKibben, Eaarth (New York: Times Books, Henry Holt & Co., 2010) xiii, book jacket. The title is deliberately mis-spelled in order to signal that the planet onto which you and I were born is not the same planet we inhabit today.

18. To learn about your region’s environmental concerns, contact your local chapter of Sierra Club. To view climate risks and clean energy opportunities in each of the 50 states, visit Climate Nexus: https://climatenexus.org/climate-change-usa/.

19. Brady Dennis, “Most Americans believe the government should do more to combat climate change, poll finds,” Washington Post, June 23, 2020.

20. Margaret Bullitt-Jonas and Leah Schade, “6 Lessons Coronavirus Can Teach Us About Climate Change,” Earth Day Network, March 25, 2020.

21. Georgina Gustin, “Our Growing Food Demands Will Lead to More Corona-like Viruses,” InsideClimateNews, March 24, 2020. Yale Climate Connections maintains an updated, curated list of articles connecting COVID-19 and climate, https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2020/03/key-readings-about-climate-change-and-coronavirus/.

22. Joe McCarthy, Global Citizen, “Why Climate Change and Poverty Are Inextricably Linked: Fighting one problem helps mitigate the other,” Feb. 19, 2010.

23. Damian Carrington, “‘Climate apartheid’: UN expert says human rights may not survive,” The Guardian, June 25, 2019

24. Nathalie Baptiste, “Climate Gentrification: Coming to a Community Near You,” Mother Jones, September 5, 2019.

25. Mary Annaïse Heglar, “We Don’t Have to Halt Climate Action to Fight Racism,” HuffPost, June 12, 2020. Yale Climate Connections maintains an updated, curated list of articles connecting racism and climate, https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2020/06/the-links-between-racism-and-climate-change/.

26. Migration and Climate Change, No. 31, IOM International Organization for Migration, 12.

27. “Climate Change Increases the Risk of Violence Against Women,” UN Climate Change News, November 25, 2019.

28. John O’Loughlin and Cullen Hendrix, “Will climate change lead to more world conflict?,” July 11, 2019, Washington Post.

29. Pope Francis, Laudato Si – Praise Be to You: On Care for Our Common Home, 2015, par. 139.

30. Leah D. Schade and Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, eds. Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

31. Peter Sawtell, “Three Layers of Environmental Preaching.”

32. https://episcopalchurch.org/beloved-community/.

33. In order not to burden the sermon with a laundry list of resources and options for action, I usually put a handout of suggested actions in the service leaflet. The Episcopal Church’s Creation Care Website offers some suggestions, including the carbon tracker now used in many dioceses (https://www.sustainislandhome.org/).

34. Sarah DeWeerdt, “Here are a half dozen nudges that could bring about rapid decarbonization,” Anthropocene, January 21, 2020.

35. DeWeerdt, “Here Are a Half Dozen Nudges that Could Bring about Rapid Decarbonization.”

The One Home One Future campaign springs from the conviction that people of faith have a moral imperative to safeguard children, communities, and future generations. The holy scriptures of the world’s Abrahamic religions teach that God’s creation — the Earth — is sacred and that we are called to protect each other and the world that God entrusted to our care.

The One Home One Future campaign springs from the conviction that people of faith have a moral imperative to safeguard children, communities, and future generations. The holy scriptures of the world’s Abrahamic religions teach that God’s creation — the Earth — is sacred and that we are called to protect each other and the world that God entrusted to our care.